Amy Chavez is an American who lives (and writes) on Shiraishi Island in the Seto Inland Sea. This talented wordsmith has lived in Japan for almost 30 years. Chavez was a columnist for The Japan Times from 1997 to 2020 and has written articles for various publications. In addition to her own website, she runs the Books on Asia website and podcast.

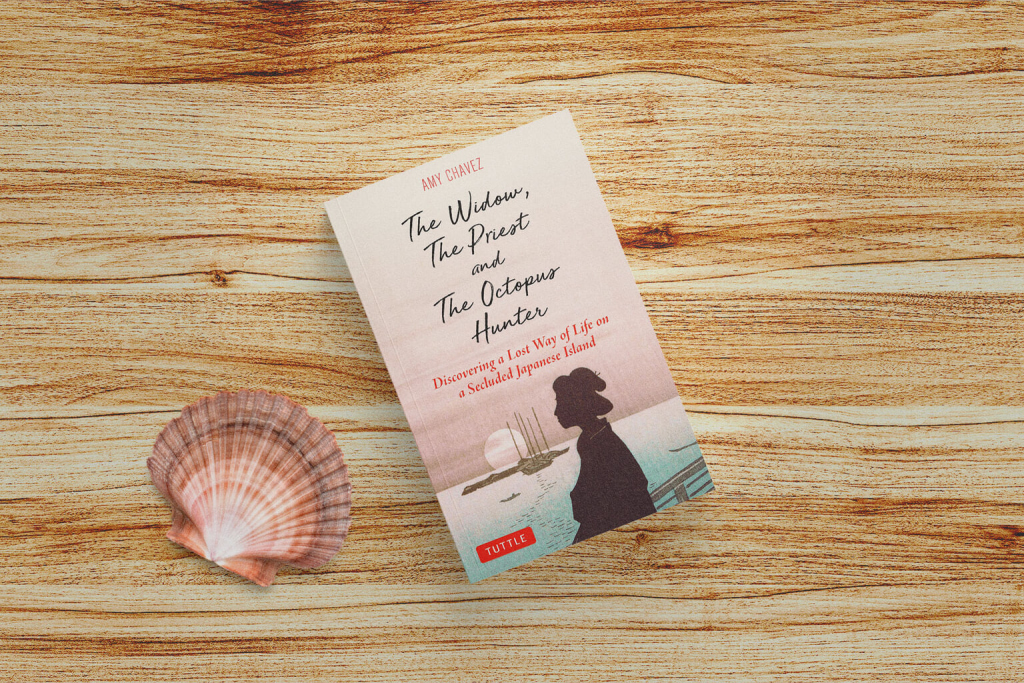

She has just published her fourth book, The Widow, the Priest and the Octopus Hunter: Discovering a Lost Way of Life on a Secluded Japanese Island. It’s a collection of intimate portraits capturing the lives of 31 residents living on Shiraishi Island in Okayama Prefecture.

Chavez has been a pillar of the Shiraishi community for years. She even runs a beach bar on the island. In 2015 and 2017, she organized the “Run with Kobo Daishi Trail Race” and raised thousands of dollars to clean up and increase awareness of the Shiraishi Pilgrimage.

We caught up with Chavez to find out more about her books and her life on an island with a population of just 430 people.

1. Can you describe your new book in one sentence?

It’s an oral history of Shiraishi Island revealed through conversations with the residents who relate stories that span four periods of Japanese history: Taisho, Showa, Heisei and Reiwa, so 1912 to 2021.

2. Can you tell us about your three other books and why people should read them?

Japan, Funny Side Up is a selection of ‘Japan Lite’ humor columns from The Japan Times. The content is indicative of Japan in the 1990s and 2000s, so read it to learn what the country was like then (hint: completely different).

Running the Shikoku Pilgrimage is about my sojourn on the Shikoku 88-Temple Pilgrimage route over a five-week period in 1998. I used to be a long-distance runner, so I fast packed the 1,300 km pilgrimage and wrote about my experiences. In 1998, the pilgrimage wasn’t popular among foreign tourists yet and there wasn’t an English guidebook or technology such as Google maps to help pilgrims. The second, updated edition of this book will be published next year. That new version will consider how the pilgrimage has evolved over time and includes reflections from subsequent trips to Shikoku.

Amy’s Guide to Best Behavior in Japan is a culture vulture’s guide to the customs and etiquette of Japan. To research the book, I talked to managers of hotels, okamisan of traditional Japanese inns, restaurant owners and others in the service industry to get an idea of what they wish tourists knew. Manga-style cat illustrations by Jun Hazuki endeavor to show rather than just tell tourists about etiquette. For example, everyone knows to take off their shoes before entering a Japanese house, but did you know there’s a proper way to take off your shoes? There’s a cat to show you that.

It has taken me decades of living in Japan’s polite society to realize these secrets of Japanese manners and I wanted to pass them on to others. Especially because the Japanese will never tell you.

Amy Chavez

3. Why do you prefer to write non-fiction and do you plan to write fiction in the future?

For 25 years now, I’ve written mainly from experience and a fervent desire to share my stories. I’ve noticed my experiences are often vastly different from other expats who are living in the cities, which I think attests to how diverse Japan is. Fiction? I’m still trying to fine-tune the non-fiction.

4. Can you tell us about the website Books on Asia and what kind of literature you prefer to read?

Books on Asia is my attempt to compensate for the diminishing cover newspapers are assigning to book reviews. My aim is to provide a space to highlight and recommend outstanding books on Japan and Asia. My interest in Asia isn’t limited to Japan. However, Japanese literature in translation, travel books on Japan and outsider exposés are so popular, that keeps me busy enough.

I also host the Books on Asia podcast where I’ve had the opportunity to interview some amazing authors and translators on Japan.

I’m a voracious reader myself. I love Japanese literature, both classic and contemporary. Lately, I’ve been reading a lot of Japanese poetry. I try to read poetry every day.

Shiraishi Island

5. Why did you decide to live on Shiraishi Island and what is life like there?

When I came to Japan in 1993, I lived in Okayama City while teaching full time at a Japanese university. But after four years, I wanted to delve deeper into traditional Japanese culture, so I started looking for a place to live outside the city. Okayama Prefecture is on the Inland Sea. When I came out to visit the islands, I fell in love with the setting.

A week after moving to Shiraishi, I received a thick envelope in the mail from my mother in the US. Inside was my great grandfather’s diary. He had journeyed through the Inland Sea on a military transport ship between the Philippines and San Francisco in 1900. He loved the scenery, the hard-working people he met. He also described going ashore at different Inland sea ports.

That was during the Meiji Period, just one year after Lafcadio Hearn published In Ghostly Japan, a decade after Ogai Mori published his short story The Dancing Girl, and the era in which haiku poet Shiki Masaoka established his tanka revolution. In 1901, Akiko Yosano would publish Tangled Hair, her first volume of tanka and two years hence, feminist Raicho Hiratsuka would graduate from Japan Women’s University and go on to found Seito (Blue Stocking) women’s magazine and make the celebrated claim: “In the beginning woman was the sun.”

I had no previous knowledge of any relative of mine having been to the Inland Sea — let alone during such an exciting time — and writing about their experiences. It made me feel it must have been fate that I, as a writer, landed here.

Reading The Widow, The Priest and the Octopus Hunter is the best way to understand the challenges of residing on a small island in Japan. I cover specific issues, some common to any depopulating provincial village and others unique to the Seto Inland Sea islands. It’s taken me two decades to truly understand what goes on behind the scenes here, as well as the specific values that form the life here.

Shiraishi Island dance

6. How has Covid-19 affected your daily life on the island?

The residents feel safe here since not so many of us frequent the mainland and few outsiders come to visit. So, we’ve maintained our day-to-day movements without interruption. One major downside of Covid-19 has been the cancellation of the island festivals and events. These rituals mark time, the passing of the seasons. They serve as the lifeblood of the community. Since relatives on the mainland have also stayed away it’s been especially lonely for the elderly.

7. Why did you open the Moooo! Bar & Cafe?

The Moooo! Bar has been 18 years of fun on the beach. I started this venture to help revitalize the island. Shiraishi attracts fewer numbers of travelers than mainland destinations, but as a result, we can spend more time with them. We might show guests around the island, or tell them where a good private beach is, or where the hidden pilgrimage path starts.

These days, the bar is only open in the summer (July and August) and 90 percent of our customers are Japanese. The other 10 percent are intrepid foreign travelers who come via the Lonely Planet guidebook or expats who discover Shiraishi Island via word of mouth.

8. What advice can you give to other people who want to write books and articles about Japan?

The inbound travel boom has created numerous opportunities for writers in Japan. I feel like it used to be more difficult to get published. Nowadays, publishers can’t seem to find enough warm bodies to draft travel essays, articles and books, or to promote Japan on social media. It’s a huge, dynamic market at the moment and wide open.

You can get a copy of The Widow, The Priest and the Octopus Hunter online as a Kindle book or in print.

Follow Amy on Twitter, as well as the official Books on Asia Twitter.