The philosopher Kiyoshi Miki said, “the best books are those that constantly ask us questions.” We’ve put together the following list for just that reason. Fiction and nonfiction alike can help us see Japan from new perspectives, challenging our underlying assumptions and leading us to a deeper understanding of its society and culture.

Read our first roundup of books to read to understand Japan.

Nonfiction Books

1. Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art by Susan Napier

Known internationally as the director of beloved films such as Spirited Away, Hayao Miyazaki boasts a career in animation that spans nearly six decades. In Miyazakiworld, Susan Napier tracks his evolution as an artist, from his humble beginnings as a rookie animator to co-founder of his own production company, Studio Ghibli. Her insightful analysis of Miyazaki’s recurring themes and creative choices shed light on his worldview and how his childhood was shaped by the immediate aftermath of World War II. Reading this book almost feels like taking a peek inside his head.

2. This Monk Wears Heels: Be Who You Are by Kodo Nishimura (Translated by Tony McNicol)

Makeup artist, LGBTQ activist, Buddhist monk: there’s nobody quite like Kodo Nishimura. After appearing in Queer Eye: We’re in Japan, Nishimura has used his platform to spread positivity and self-acceptance internationally. This book is equal parts memoir and self-help manual, as Nishimura shares not only his own life story, but also how Buddhist teachings have inspired him to practice mindfulness and navigate Japanese society as an openly gay individual. If you’re looking to empower yourself and broaden your perspective, let this book show you the way.

3. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan by Herbert P. Bix

This Pulitzer Prize-winning biography brings the enigmatic and controversial figure of Emperor Hirohito to life, taking an unvarnished look at his reign and how it defined an era. Herbert P. Bix meticulously combs through primary sources to paint an intimate portrait of the former emperor’s upbringing and personality, ultimately pulling back the curtain on his active involvement in Japan’s descent into militarism and wartime imperialism. No Japanese history collection is complete without this addition.

4. Tokyo: A Biography by Stephen Mansfield

Earthquakes. Fires. Air raids. Riots. Tokyo has survived all these and more, reinventing itself every time it rises from the ashes. In this book, Stephen Mansfield offers a concise history of Tokyo from the construction of Edo Castle to the present day, cataloging the disasters and revolutions that have shaped the city we know and love. He writes in a lively, dynamic style infused with fascinating anecdotes, creating the perfect read for both newcomers and longtime residents alike.

5. On Haiku by Hiroaki Sato

Haiku poetry is one of Japan’s most widely-recognized cultural exports, but there’s far more to it than just frogs jumping into ponds. The simple structure of these poems belies their incredible complexity, and there’s nobody better suited to demystifying the topic than Hiroaki Sato, who has spent the past five decades translating haiku into English. On Haiku is conversational and entertaining, a deep dive into the nuances and historical controversies of this centuries-old tradition buoyed by Sato’s unmistakable wit and enthusiasm.

Fiction Books

6. There’s No Such Thing as An Easy Job by Kikuko Tsumura (Translated by Polly Barton)

There’s No Such Thing as An Easy Job is a quirky, satirical novel about searching for meaning in Japan’s notoriously challenging workplace culture. After burning out and abandoning her decade-plus career, the unnamed protagonist takes on a series of increasingly bizarre temporary positions in search of the titular “easy job.” Her deadpan narration and droll observations are compelling precisely because they’re so relatable, making this the perfect book for anyone who’s suffered through a minimum wage job or two on the way to something more fulfilling.

Read our interview with translator Polly Barton.

7. Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata (Translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori)

Based on Sayaka Murata’s own 18-year stint as a part-time clerk, this darkly comic novel follows Keiko Furukura, a socially-awkward convenience store employee who only thrives when obeying the rules at work. As Keiko struggles with the pressure to either marry or get a “real” job, Murata urges the reader to take a long, hard look at the poor treatment of essential workers in Japanese society, an issue more relevant than ever given the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

8. Confessions by Kanae Minato (Translated by Stephen Snyder)

Celebrated mystery author Kanae Minato’s debut novel, Confessions, centers around middle school teacher Yuko Moriguchi’s quest for revenge after discovering two of her students were responsible for the death of her daughter. Borrowing a page from Rashomon, Minato alternates between six points of view, slowly peeling back the layers to reveal the truth. On the way, Confessions covers topics like bullying and the limitations of the Japanese Penal Code, ultimately begging the question: how far should a teacher go to give her students an education?

9. Out by Natsuo Kirino (Translated by Stephen Snyder)

Out is a riveting examination of the burdens that Japanese women carry day to day and the precarious friendships they form with other women. When four co-workers at a boxed lunch factory help cover up the murder of an abusive husband, they find themselves entrenched in the seedy world of organized crime. Natsuo Kirino leaves no stone unturned, making incisive observations on race, class and gender that are just as fresh and biting as they were when the novel was first published in 1997.

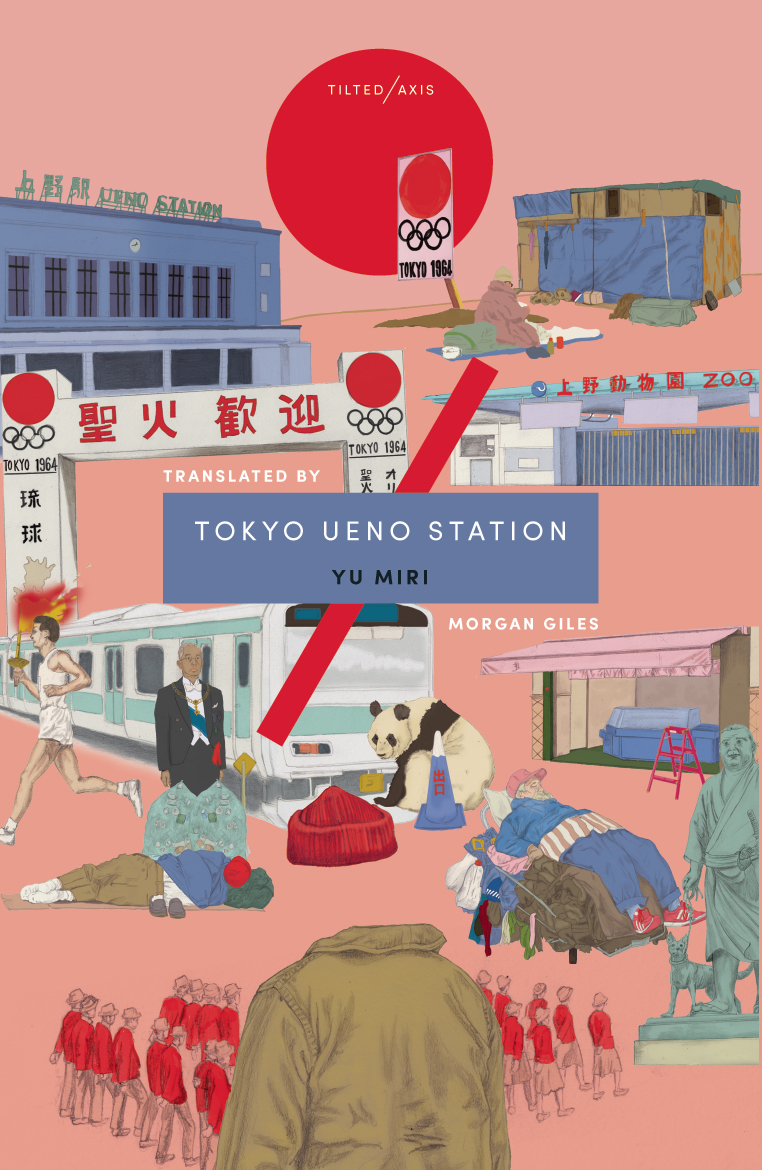

10. Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri (Translated by Morgan Giles)

Zainichi Korean author Yu Miri is no stranger to exploring the outskirts of society and in Tokyo Ueno Station, she tackles the city’s hidden homeless population. This deeply melancholic novella follows a former migrant laborer named Kazu. Born the same day as Emperor Hirohito, Kazu lives a long and difficult life, working in construction and doing manual labor for the 1964 Olympics. After a series of tragedies, he leaves his hometown of Fukushima and begins living in Ueno Park. The author brings attention to Japan’s mistreated and vulnerable homeless population, weaving in stories from her interviews with real people in the process.