Fittingly for an artist so adroitly pinning down the zeitgeist of early 21st-century Tokyo, photographer Takehiko Nakafuji was exhibiting images of what is his home city right when the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011 struck. His show was left in slight disarray, but more significantly the episode stirred Nakafuji to create a new body of work that deftly conveys a Tokyo apprehensively crossing over into the new Reiwa era, where life is becoming ever more precarious.

“Eight years on, on the surface Tokyo’s memory of 3.11 seems to be fading, but inside of me the darkness of the city after the disaster is hard to forget,” laments Nakafuji as we sit in Gallery Niépce, his exhibition space in Tokyo’s Yotsuya. Deeply shaken after witnessing the incident’s aftermath at its most severe, while shooting client work in the tsunami-devastated Tohoku region, Nakafuji returned to find Tokyo plunged into both literal and figurative darkness by setsuden (emergency power-saving measures), and widespread fear of radioactive contamination from Fukushima’s damaged nuclear power plant.

Amid the unsettling gloom, the photographer had simultaneously a sense of finality (that the decades of comfortable stability enjoyed by postwar Japan were now unequivocally over) and a foreboding that his nation was beginning an uneasy new chapter. “Japan had been sinking since the end of the bubble era, and now it was as if the country in its entirety had collapsed.”

Analogous to the “break in transmission” of the power outages, and suggestive of the invisible threat of radiation, Nakafuji recounts that Tokyo’s atmosphere following 3.11 reminded him of the static “white noise” emitted by TV sets when stations went off-air, in the days before 24-hour broadcasting.

Deciding against creating personal work out of what he saw in Tohoku (“I felt it would be imprudent, as one uninvolved in the disaster,” he explains), Nakafuji instead channeled his disquiet at post-quake Tokyo into a still-growing collection of work depicting the city with which he has an avowed love-hate relationship, as it grapples with such intertwined issues as a still stagnant economy; redevelopment prompted by the coming Olympics; an uncertain place in the world order following China’s ascent; and a seeming resurgence of nationalism.

“It’s chaos, with the old being destroyed and new things created with no sense of order. There’s a confusion, of a kind that can’t be seen in any other city in the world”

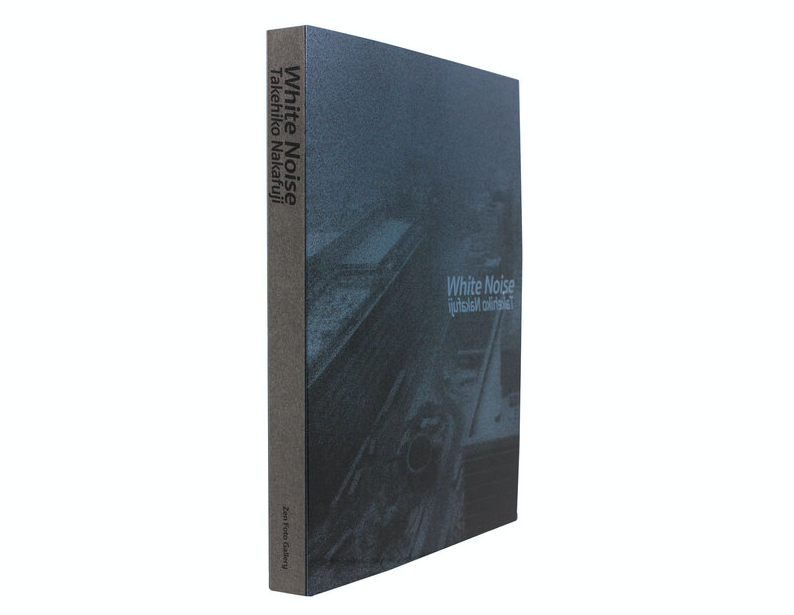

White Noise, a photobook published late last year, takes its title from the artist’s almost hallucinatory impression of Tokyo in the weeks following 3.11. An elaborate and ingenious design has each page unfolding to reveal an additional concealed image, forming an immersive, multi-layered object that mirrors the labyrinthine mayhem of the city itself. This disorder is intensifying in the ramp-up to the 2020 Games, observes Nakafuji: “It’s chaos, with the old being destroyed and new things created with no sense of order. There’s a confusion, of a kind that can’t be seen in any other city in the world.”

Nakafuji’s work has hitherto been considered part of the abrasive, ultra-high contrast monochrome tradition emblematic of post-war Japanese photography and pioneered in the 1960s by, among others, his former teacher, the legendary Daido Moriyama. Through tackling post-3.11 Tokyo, however, Nakafuji is transcending such influence to find a voice truly his own. Here an idiom informed by the inherently vague, photographic abstract expressionism of Moriyama and similar forebears is infused with a degree of direct social commentary.

Yasukuni Shrine, symbolic for many of the aggressive imperialism Japan pursued in the 1930s and ’40s and a modern-day nationalist rallying point, makes for Nakafuji’s most overtly political images. “When I visit Yasukuni on the anniversary of the end of the [Pacific] war, I wonder just what era I’m in,” he broods. “It feels like Japan is gradually returning to the pre-war period.” Indeed, Nakafuji’s image of an unbroken sea of Hinomaru flags, paraded up the avenue leading to Yasukuni on that date, could have been made back in the days of the empire’s euphemistically named Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

At the other extreme of pomp and grandiosity, Nakafuji’s work shows us downtown districts retaining the atmosphere of the late Showa period in which he grew up. The photographer feels an affection for such places: one affirmative aspect of his love-hate relationship with the capital. These streets are sometimes depicted in a romantic light, but just as often seen beaten down by inclement weather, suggestive of the buffeting such neighborhoods have taken from decades of a moribund economy, and now rampant redevelopment. Perceptible too is the lingering fear of radioactive pollution. The oppressive blackness of setsuden hangs heavy over such images.

Elsewhere Nakafuji conveys his sense that metropolises function in a way akin to living organisms, which comes across as something perceived viscerally as much as intellectually. In the Japanese capital’s case, he recognizes an out-of-control monster. “It’s as though Tokyo is some huge creature with its own volition.” This ‘entity’ is made manifest in an image shot in Ikebukuro which, together with Shinjuku, is the subject of some of Nakafuji’s grittiest work. The eye of a whale, part of a piece of street art, emerges into an almost psychedelic color scape whose suggestion of toxic contamination is sufficient to make the viewer choke.

The same photo also evinces the most conspicuous development in Nakafuji’s post-3.11 work: his bringing of color into the photographic mix. It was explicitly Tokyo that inspired this move, after years of working purely in black-and-white. “I felt that an extreme, highly processed color was also needed, in order to express the strange madness and overdone beautification of today’s Tokyo.”

Color is also deployed to obliquely deride the reverence with which Japanese nationalists look back upon the country’s imperialism. A realistic-looking diorama of an autopsy, shot inside a now-closed museum, is given a color treatment reminiscent of vintage hand-tinted photo postcards. “In my mind, this somehow connects with Unit 731,” says Nakafuji, referring to the Japanese Imperial Army’s secret program of live vivisection of thousands of individuals in occupied northeast China. The warmly nostalgic coloring, combined with the photographer’s historical free association, seems to ask incredulously, these were Japan’s halcyon days?

Having nailed Tokyo’s grungiest backstreets and most politically charged sites, Nakafuji is presently turning his lens towards Shibuya, a district in which he perceives a terrible soullessness, symptomatic of much that has gone wrong in recent years. “In photographing this area I truly dislike, I think I may be able to express something emblematic of modern Tokyo,” he muses. “When I watch the endless waves of people and traffic over the scramble crossing, I strongly sense I’m seeing the cells and arteries of that giant creature.”

White Noise is available for ¥6,480 from www.shashasha.co/en