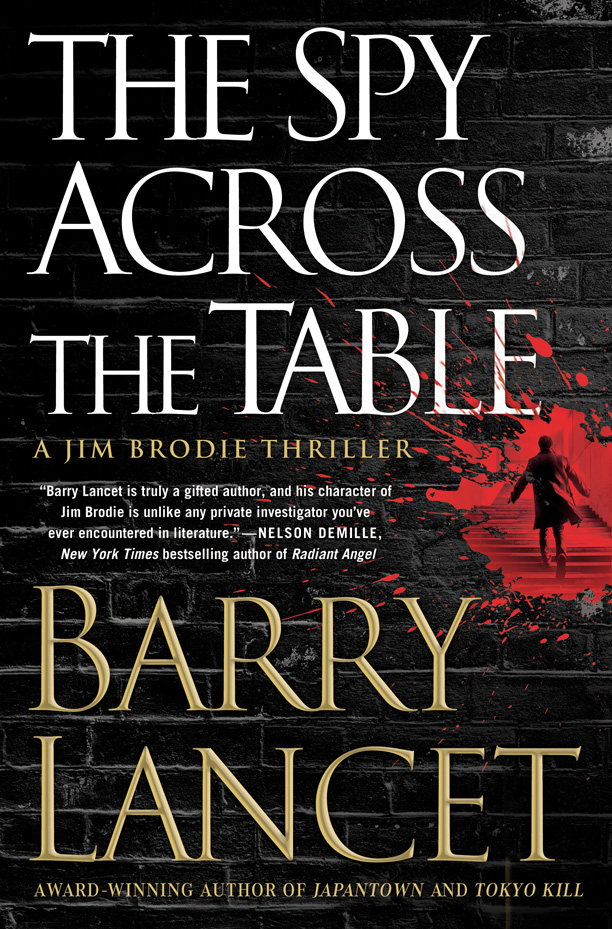

You might think that writer Barry Lancet has a crystal ball somewhere around his writer’s desk, given how topical his most recent book, The Spy Across the Table, manages to be. Its plot wends its way into North Korea, and features a character who is a high-level Chinese spy. But this is all in a day’s work for Lancet’s creation Jim Brodie, the art dealer/private detective who is sleuthing and fighting his way through his fourth novel.

After two of Brodie’s close friends are murdered in Washington DC, he is drawn into a tangled web of action that takes him to one of the world’s most tense geopolitical regions – the demilitarized zone that lies between North and South Korea. He also delves into corners of Japan’s underworld, including the Chongryon, a Japanese Korean group with ties to North Korea, and the PSIA, Japan’s national intelligence agency.

The taut thriller is full of surprises, and keeps the double- and triple-crosses going almost until the very last page. At the same time, it provides plenty of local color and intriguing cultural and historical details without falling into the trap of exoticizing its foreign locations and characters. Before launching his career as a novelist, Lancet was a book editor with Kodansha International, and you’d be hard-pressed to find another thriller writer who knows the ins and outs of Japanese society as well as he does.

The Spy Across the Table just hit the shelves last month, and we caught up with Lancet just before he was going on his US book tour. Over coffee at Shinjuku’s legendary jazz café Dug, he spoke to Weekender about using fight scenes to show that brawlers are anything but just dumb brutes, the real “spy across the table,” and what he sees as the greatest strength of his protagonist, the unflappable Jim Brodie.

I’ve always been impressed by how thought-out your fight scenes are. How do you choreograph them in your mind?

I’m not really quite sure, but I’ve always had a dissatisfaction with the way fight scenes were done in a lot of the books I read, whether it’s detective fiction, thrillers, or even contemporary literature, and I always thought that they could be done better, so that’s why I spent a lot of time to get them right. To me, just like a conversation, or a pivotal event in somebody’s life, there can be a lot of psychology in the actual fight scene. They’re trying to suss out their opponent on a number of levels – not every fight, but a lot of fights. And that’s what I often try to show.

Between your first book, Japantown, and your most recent one, has your writing process changed at all?

I think the tone of the book has changed. I think it has grown tighter. I always try to up the level with each book in one or more ways. Like a lot of crafts or arts that people take their hands to, writing is a never-ending reaching for the next level … I interviewed another writer who’s been around for a long time named Thomas Perry, and he basically said the same thing: If you can’t write something original, and can’t improve with each book, for him, there wasn’t much point. For me, I feel pretty much the same way. It’s very satisfying when you can raise the bar on yourself, and that’s what I try to do.

How long did The Spy Across the Table take you to write?

This one took a little more than a year, and a little bit longer than average, because I’ve got five countries this time. I promised myself after Tokyo Kill, which had three countries – China, Japan, and America – that I was just going to stick to two countries. Doing that extra research and getting it right was really a tremendous amount of work. For the next book, Pacific Burn, I did. But with this book, it went the other way, because that’s just where the characters went. Things fairly quickly went from US-Japan to the whole South Korean, North Korean, and China nexus.

How much do you plot out the books before you write them?

There’s always an image or an idea that I start with, and that sometimes takes the form of an opening scene or a scene near the opening, plus a couple of events beyond that. And then around that, a theme develops. I don’t outline, because outlining limits the possibility of the story; on the other hand, I don’t like going in a completely wild direction, but I like to keep possibilities open, and a lot of times, new and better solutions suggest themselves.

Did you imagine that the book was going to become as topical as it has been, given the current situation in North Korea?

I had no idea that events were going to develop between the US and North Korea and China as they have. But the book talks about the real way that North Koreans think, and what’s going on in North Korean society, and the press is just starting to come out now. The cliches and the accepted things have been changing rather drastically since the famine in North Korea [1994-98], which really opened North Korean’s eyes to the fact that they can’t rely on their leaders any more.

What advice would you give to any world leader who is having to deal with the “Hermit Kingdom”?

Most of the experts who I trust say that the Kim dynasty is stagecraft. They’re not dumb, they’re not insane: what they’re doing is very well calculated, and it’s clever, and it’s a way for a very small, nearly powerless country to wag the dog.

How did you research the intelligence organizations that you write about in The Spy Across the Table?

With the NSA, there’s a lot of information that’s already out there. The PSIA is a little more discreet. It’s a fascinating little place, because they really like to keep a low profile. You don’t know they’re there, and most Japanese have never heard of them. There isn’t a lot of information about them, and they don’t encourage people to look into what they’re doing.

Have you had any interactions with people from the world of espionage?

One of the main characters in The Spy Across the Table is a top-ranked Chinese spy. He first appeared fictionally in Tokyo Kill, and a lot of people liked him as a character so I had planned to bring him back. I had a set scene in this book where he was just supposed to appear for just two or three chapters, but he sort of took over the book. I wasn’t even really expecting it.

But he’s based on an encounter that I had with a guy. I didn’t know it at the time, but I realized it later. We sat and talked for about an hour. It was a very intense conversation and I realized in the last 10 minutes of this conversation what he had been up to in the first 40 or 50 minutes of the conversation. He had been plying me with drinks to get information out of me.

What do you ascribe the popularity of the Jim Brodie books to?

I think that it’s a different world view and a different take of what’s going on in Asia. What I try to do with the books, because I’ve been here for a long time, I try to show things two or three levels below what everybody sees. Everybody knows the superficiality, and the exotic, but I go deeper. I don’t think there are a lot of people that do that; there are a lot of writers that come and poke around and choose one subject and they write about it and they go away, but I’m trying to go deeper, and I think that’s part of the appeal.

As a writer, what are some of the things that interest you most about Jim Brodie?

His ability to see both sides of the coin without making judgement – even when there are three sides to the coin, or four. That to me is quite fascinating, and is quite fascinating to anyone who spends any time in a foreign culture, particularly in an Asian culture, where you’ve got such deep roots, which are often convoluted and vague, even to the natives.

Do you have any personality traits that you share with Brodie himself?

I’ve always been very open minded and willing to try anything at least once, and willing not to judge immediately. The other thing that the Japanese do, and that they’re forced to do because of the way that society is arranged, is that they have to hold completely contradictory ideas in their head at the same time without making any moral judgement or without rejecting either one or feeling any revulsion. For a Western person who has a certain moral makeup, that’s very hard to do. And understanding that, and how it works and the dynamic behind that is something that took a lot of time. I now can do that when I need to . . . If you worked for a Japanese company like I did, it’s survival instincts, it’s a necessary thing.

Does Brodie ever do anything that surprises you?

Well, he says things that surprise me. More accurately, he’ll come up with lines that surprise me. I love to write dialogue and when I can get one line of dialogue that does several things at once, that’s something I’m really happy with. And occasionally I can get a line that will do four things at once. Sometimes readers see it and sometimes they don’t. It’s not just Brodie, though; other characters do it as well. I’ll sometimes give other characters better lines than Brodie: if the hero’s always beating everybody down, that’s not so interesting! [laughs]

The Spy Across the Table is available on Amazon Japan and at some Kinokuniya Stores, including the expanded English book store in Shinjuku’s Takashimaya Times Square, on the 6th floor, behind Tokyu Hands.