Spend a few hours on Tokyo’s streets, and it’s not hard to see that Evangelion rules the Japanese anime scene.

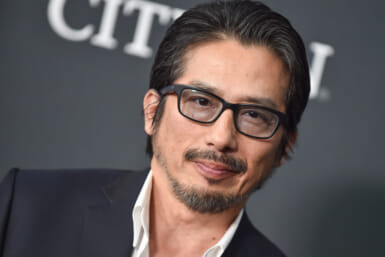

Christopher O’Keeffe

Whether you see them peering down from billboards and pachinko parlors or staring out from the covers of magazines, the hulking purple EVA robot and pilots Ayanami Rei, Asuka Soryu Langley, and Ikari Shinji seem to be everywhere. The impact of the 1995–96 series on the anime world, and on pop culture itself, makes Evangelion’s creator, Hideaki Anno, one of the most important men in an industry that dominates Japan’s modern cultural landscape.

With this month’s Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF) aiming to shine a spotlight on Japanese animation, whom better to focus on than Anno, an animator whose career spans over thirty years and reaches beyond his most famous creation to include award-winning animation, live-action features, and acting roles. Speaking to Weekender from the Khara Inc. offices, the company that he founded and where he sits as president, Anno opened up about a life in animation.

Early in his career the young animator was given a chance to help out on Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, creating the impressive “God Warrior” in the groundbreaking animated movie. When asked what words of advice he received from the animation master, he recalls words of guidance both practical and profound: “He gave me a lot of technical tips, but he also reminded me that ‘our minds are set to create things.’ He also told me not to worry too much about sleep!”

TIFF’s focus on both Anno and animation in general is timely, coming as it does so soon after Studio Ghibli, for so long a major force in the industry, has announced it no longer has any works planned or in production. But the man who Miyazaki cites as his protégé never had the feeling that he would succeed Miyazaki at the storied studio: “I didn’t have the notion of Ghibli as an independent thing; rather, Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki-san are so closely connected. I always thought that, when Miyazaki stops working, Studio Ghibli will close. There was no notion that it was going to grow by itself.”

The animator’s directorial debut was the extremely popular direct-to-video GunBuster (known in Japanese as Toppu wo Nerae!)—also an anime featuring giant robots and a young girl tasked with operating a machine in order to save the human race from a mysterious alien foe. This would be followed by the Animage Anime Grand Prix–winning television series Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water. When asked what he learned from GunBuster, and what aspects of it he wanted to carry over onto subsequent projects, he thought for a while before responding. “That’s a difficult question. When I made GunBuster, I was trying to make it simple and entertaining, but it was an inflation of Gundam [Perhaps the mother of all giant robot anime] in a way and it was complicated but I wanted to make it a little bit simpler. And that’s the intention of Evangelion—somehow it came out a little complicated but that wasn’t my intention. Eventually, as it came out, it become more complicated than I wanted it to be.”

It’s interesting that with Evangelion and a lot of Japanese animation work, much of it is not specifically aimed at children, yet the main protagonists are often kids, particularly young girls, contrasting with western work were the principal characters are often much older, and the heroes are so often male. Anno makes an interesting case for the use of children in his own work. Anno makes an interesting, and surprisingly practical, case for the use of children in his own work. “I just want to make the anime real. If grown-ups were getting ready to pilot a robot, if you were old enough or wise enough—you wouldn’t do that, you would think better of it! So in order to keep that reality you need the protagonists to not be elementary school age, and not high school age—but junior high school students would be naive enough to climb up on a robot!”

Neon Genesis Evangelion first aired in 1995 and told the story of the pilots and support staff of a facility created to fight mysterious “Angels” that are attacking the earth. The show features religious imagery and complex themes from the start, culminating with the final two episodes being completely abstract in form and taking place inside the head of lead character Shinji. Although Gainax, a company that Anno cofounded, made the series, I wonder if there was anyone above him at the time who panicked at the thought of ending the series this way. Again Anno is quick to answer but includes a caveat in his response: “No, there was not that reaction. The production team was working and communicating closely; therefore there was no friction whatsoever. They were saying ‘come on, let’s go for it!’ That was the reaction, apart from the producer of the TV station.”

Anno was aware that he was doing something quite daring and bold with the series and goes on to reveal a surprising plan of action he had to deal with its difficult finale. “Actually I pitched an even bolder idea—we thought we would not be able to produce and fill that 30 minute time slot, so we—myself and the producer—were going to apologize for 30 minutes on live TV, but then even our ‘apologizing plan’ was turned down.” After the airing of these two episodes there was quite the fan backlash and Anno himself received abuse and death threats from certain quarters. He didn’t seem fazed by the anger, though: “I was expecting stronger negative feelings!”

Famously he included some of the death threats on screen in 1997’s The End of Evangelion, a film that attempted to clarify the story’s ending, if only slightly: “As the series goes on I simplify things more and more; probably in terms of story it gets messy but actually the theme is delivered to the audience by simplifying things extremely. Those who were looking for a story were upset, but those who were searching for a theme were content, I guess.”

This seems fitting, as one of Evangelion’s qualities has always been its unanswered questions. So how does the man in charge decide which questions to answer and which not and are audiences expectations ever taken into consideration?

“I don’t make it by myself. Often things are tweaked through discussions with the production team. We don’t dare to listen to the audience but we share their feelings, so in that sense the production will change slightly.” Another key feature of the series is its use of occidental religious imagery—Christianity and Judaism, for example—that far overwhelms any symbolism drawn from Japan’s native religions. It turns out that this has more to do with the visual impact than any spiritual significance: “From the Japanese personal point of view, western religious imagery is more mysterious than Buddhist or Shinto which is a part of our daily life: that’s why I chose the western elements.”

Along with his animated hits Anno has made several live-action features, including the excellent drama ritual, which chronicles the relationship of a disillusioned film director and a mysterious young woman. While the film feels like a very intense, personal work, Anno insists it wasn’t based on his own experience but “more on the feelings that I had that I hoped would be reflected.” The director character in the film—whom Anno admits to identifying with—at one point delivers a cutting monologue: “In Japan today all forms of expression beginning with images serve only as either time killing entertainment for those without occupation or a momentary respite for those who are afraid of pain.” Anno confirms these words as his own belief: “That is exactly what I thought. That’s the words from the heart and so I couldn’t lie.”

While being an accomplished director, Anno has also managed to get a good deal of acting experience under his belt, the most high profile role being the lead in his mentor Hayao Miyazaki’s final film, last year’s The Wind Rises. Despite the weight of the role he is pragmatic about the work: “I was just trying to satisfy Miyazaki-san as that’s what he asked me to do. I wasn’t following any kind of acting plan, I just wanted to help him.” As for Miyazaki’s choice of final film he says, “I was happy with it; I thought it was good, but I’d like to see one more from him.”

Given Anno’s links to Studio Ghibli, he appeared on stage with head honcho Toshio Suzuki at a recent TIFF press conference and it was Suzuki who encouraged him to work with the festival. Is there any chance he might step in and make a film under the Ghibli banner? “No, Thank you!” comes his definitive answer, and he also swiftly dispatches any rumors of a sequel to Nausicaä being made.

With the fourth, and final, film in the Evangelion film series scheduled for release next year, along with the 20th anniversary of the release of the original series there should be some major celebrations in the works, but if there is, its creator isn’t giving anything away.

Do you have any plans for the 20th anniversary of Evangelion?

“That’s not my job!” What’s the plan after Evangelion is over?

“I’m thinking now!”

A return to TV, a film?

“Haha, no comment!”

While the director is keeping his cards close to his chest, when it comes to future projects he ends with some wise words for any animators hoping to make their own impact in the competitive world of anime: “An animator is a photographer, animator, actor, everything is in one person. In order to widen your world you need to experience more and force yourself to experience new things; otherwise your creation will only get smaller and smaller.”

To find out more about the Tokyo International Film Festival’s Hideaki Anno Screenings, visit their site at 2014.tiff-jp.net/en/

Main Image: Evangelion © Khara