Japanese Buddhist philosopher D.T. Suzuki once wrote, “Technical knowledge is not enough. One must transcend techniques so that the art becomes an artless art, growing out of the unconscious.”

This certainly applies to artist, designer and photographer Shouya Grigg.

Grigg is the creative mind behind Sekka Lab, Zaborin, Somoza and Shiguchi, four hospitality ventures on the outskirts of Niseko, Hokkaido Prefecture. “In some ways, I don’t really have a formal background in any of the areas I’m presently working within,” he says. “I realize now, much further down the line, that this really worked in my favor.”

What’s Your Story?

Grigg has now spent over half of his life in Japan, living and working in Japan’s northernmost prefecture. He first established himself as a graphic designer and commercial photographer in Sapporo and ran his own design studio. In the last decade, however, he has become a household name in the Japanese hospitality industry — especially in the Niseko area.

After graduating from high school, Grigg pursued studies in filmmaking, media and design. “In some ways, the reason I was interested in filmmaking, I guess one of the big reasons, is I’ve always been interested in storytelling. That and the power within the stories that we tell to others and ourselves,” he says.

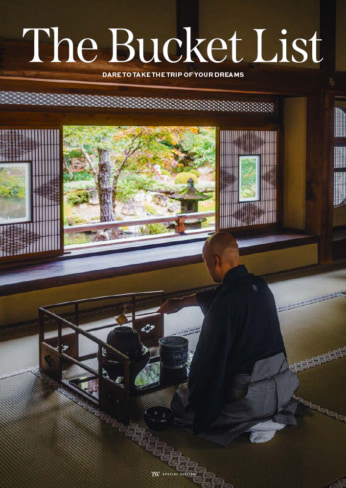

When describing his work today, he continues, “In Japanese, I often talk about it as being ‘ikiteiru eiga,’ or living cinema,” he says.”When you think about storytelling and making a film, often the filmmaker will pick up stories that they’re interested in.”

He elaborates by breaking down the steps of film production: selecting a story, finding a location, building sets, decorating with evocative pieces and bringing in crew and talent. “I’m not doing this in such an obvious way. I am following the same process in the hotels I create — it’s just that this time the actors and actresses are the guests and the film doesn’t have an ending,” he says, laughing.

His actions contradict his words — there is a clear intention with every creative decision Grigg makes.

“A lot of what I’m interested in is also found within the hospitality industry,” he says. “What I mean is I’m interested in architecture, interior design, cuisine, people — the list goes on.”

Grigg naturally made the switch from media design to architecture and interior design 17 years ago. But without any training in those fields, it was difficult to get his first clients. “That’s when I decided to do my own first project,” he says. His first folio piece was Sekka, a wine bar-restaurant.

The Art of Curation

“Generally what I’ve always been interested in is not the commercial. It’s more the boutiques, the smaller properties and businesses,” Grigg explains.

Though Grigg’s projects are often described as luxury accommodations or experiences, the artist doesn’t feel “luxury” hits quite right when considering his work. The difference between luxury and boutique in any industry, simply put, is curation. And curation is what makes Grigg’s projects so impactful. “I don’t design just for the sake of design,” he says.

Instead, every detail is crucial to the overall story he is trying to tell; there are no small roles in his masterpieces.

The big difference between a designer and an artist, he explains, is that designers have clients, who pay for a service and also have a voice. “Usually as a designer, you cannot really create 100% of what you want to create,” he says. “I did some of that, and I realized I don’t want to be a designer. I’m not commercial.”

Grigg continues, “My main intention is not driven by business.” Having lived in Hokkaido for nearly 30 years, Grigg sees his work as a way to give back to the community, to his adopted country and to the world. “Growth and contribution are, I think, the strongest needs of human beings,” he says.

In everything he does, Grigg is trying to create something that wasn’t there before.

Shiguchi, Sister Project to Somoza

Opened in the spring of 2022, Shiguchi is the continuation of the second chapter of a trilogy of projects. “Somoza was the first part, or the first scene, of the second part of the trilogy,” he explains.

The first chapter of the trilogy, Zaborin, was the product of a collaborative effort. “My business partners left a lot of it to me in terms of the design and the concept,” he says.

But with partners, as with clients, there was compromise.

Grigg started working on Somoza soon after the opening of Zaborin and tackled the project as the sole director and producer. He sought to explore his limits while having full creative freedom. “I wanted to see how far I could take it,” he says.

Somoza was a success and gave Grigg the confidence and growth he needed to then work on Shiguchi.

Grigg’s creative process, in his own words, is “a form of meditation practice.” His nature walks near his home in Niseko and his meticulous photography work that he prints on washi paper and retouches by hand using charcoal are ways he attempts to reconnect with nature and his true self. This aspect of his work, he explains, is crucial to understanding the purpose of Shiguchi.

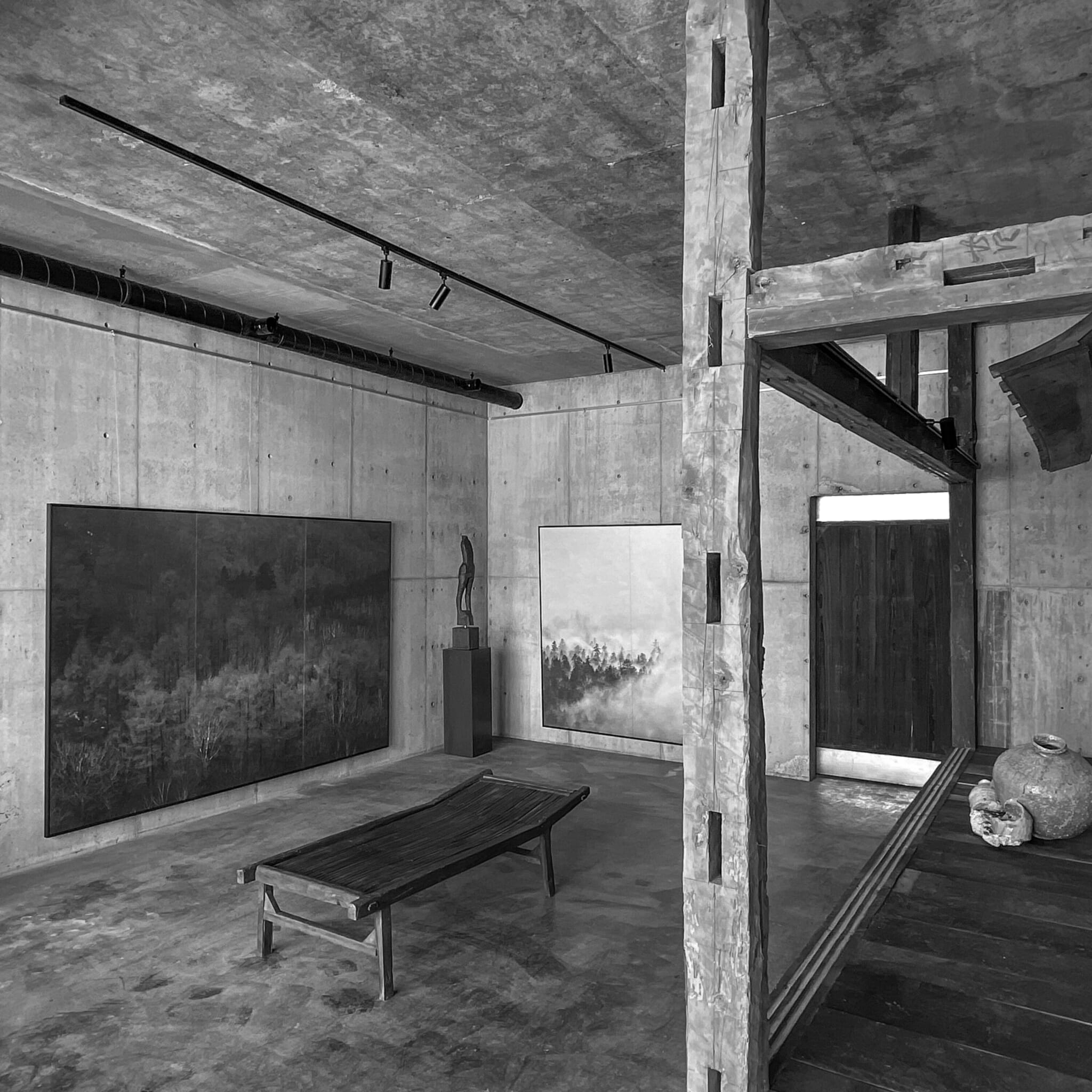

Somoza and Shiguchi intertwine art, antiques, interior design and nature — both in the decor and buildings themselves — showcasing aspects of Grigg’s intimate relationship developed with his artistry. With Shiguchi, he hopes to inspire people to connect with nature and their true selves, and eventually connect with others. This is what inspired the name “Shiguchi,” which refers to the joint between two pillars. It was especially common in the building of kominka (Japanese folk houses).

Connecting With What Matters

Grigg believes that his interest in kominka spawns from his parents, who renovated houses in the UK. “I’ve always been interested in old properties and old buildings,” he says, continuing to explain that he connects better with older structures. “There’s some essence, there’s some power that I believe is captured within them.”

The artist also has his parents to thank for his passion for antiques. Both Somoza and Shiguchi are decorated with pieces from Grigg’s personal collection of Japanese ceramics and artworks. “All of the pieces I use to design or create, all have some meaning and a certain energy captured within. What makes it interesting for me is the new narrative and overall increased power and energy that I can create by combining the various pieces.”

For Shiguchi, Grigg found, relocated and renovated five kominka from Aizu in Fukushima Prefecture. With Hokkaido being a more recently developed prefecture, there are few old properties to renovate and repurpose. Kominka are unique structures in that they can be taken apart and rebuilt somewhere else relatively easily. For the artist, this allows for the creation of new narratives while also honoring history.

If the villas act as sets in Grigg’s film, then every guest plays a role. The villas were designed for introspection and for visitors to get inspired by their surroundings. Every antique, every work of art, every pillar has its story: that of the artist, of the sculptor, of the carpenters who constructed the kominka. “Older pieces were always made by hand. There’s some energy from the person who’s making that that’s captured within that piece,” Grigg says.

When working on Shiguchi, the artist hoped to create a space that simulates the effects of meditation or rekindles a sense of wonder. “What I’m trying to do, through what I create, is connect people.”

“Shiguchi is where we connect the guests to the things that matter,” he continues. In many ways, this connection is something accommodations don’t traditionally offer. This is what Grigg calls “a new generation of hospitality.”

To learn more and to book your stay, visit the Shiguchi website.

Updated On July 6, 2023