We speak with an American photographer who found inspiration in the art and skill of Japanese bonsai masters, whose botanical creations can be found in Washington DC’s National Bonsai and Penjing Museum.

Once a work of art has been created and put out into the world, that is usually that: you’re unlikely to find a sculptor who would return to one of their pieces once it had been installed, and as much as they might want to, no writer is going to walk into a bookstore to make amendments to copies of their novel that might be sitting on the shelf. But, when it comes to the art of bonsai, a piece is never really finished. It can take years of pruning and guiding branches to achieve the shape that a bonsai master might want. Then, in the years that follow, the tree must be carefully attended so that it maintains its shape, size, and health. It’s a process that never ends: the artisans who “train” the trees continue to work on them for decades, and it is not unusual for bonsai pieces to outlive those who first helped bring them into being.

Miyajima White Pine, in training since 1625. This tree survived the bombing of Hiroshima, and was given to the US by bonsai master Masaru Yamaki (photo ©Stephen Voss)

Bonsai is a manifestation, writ small, of the aesthetic and spiritual qualities that Japan holds most dear: attention to detail, patience, and an appreciation for nature, and given the extraordinary amount of work that goes into each of the pieces, when they are given as gifts, it is a great honor – and a considerable responsibility. In 1976, the government of Japan presented the US with 53 bonsai in honor of the country’s bicentennial. From this initial gift, the Museum expanded its collection, adding bonsai made from trees native to the US as well as examples of penjing, the horticultural art that was developed in China and preceded bonsai by a few centuries. Now, Washington DC’s National Bonsai and Penjing Museum is one of the country’s most celebrated collections.

As well as serving as examples of soft diplomacy – reminders of ties that connect nations even during times of strain – these miniature trees are sources of aesthetic inspiration to everyday visitors who drop by the Museum. One of those people was Stephen Voss. Now a professional photographer whose lens is trained on politicians and other figures who shape business and global policy, Voss was first drawn to the bonsai as a university student 17 years ago. “From my first glimpse of the trees all those years ago, I knew implicitly that there was something to be learned from them, from their endurance and quiet dignity.”

Over the years Voss kept returning to the Museum, but he didn’t decide to connect his professional life as a photographer to his personal appreciation of the bonsai until last year, when he began a project that brought the two worlds together. Over nearly a year, he would photograph each tree at the Museum, but at a leisurely pace that he would never have with the politicians and businesspeople he often shot. It was a painstaking process, and it didn’t always work out, Voss explains. “I would choose a single tree and spend hours immersed in it, trying to make a visual record of the spirit of the tree. Sometimes I would find an image, sometimes not.” As he examined the bonsai and penjing pieces, he found similarities to the portraiture that he did professionally: “The trees absolutely have personalities and sometimes can be just as challenging as people in trying to bring them out. The emotional resonance of different trees is so varied – some feel heavy and dramatic, while others are lightweight and carefree.”

At first, Voss intended for the photos to be a part of his personal portfolio, but after receiving a lot of positive feedback about the images, he decided to share the pictures with the public. Halfway through his project, he shared his photos with the chief curator of the Museum, Jack Sustic, who put him in touch with two other American bonsai masters, Michael Hagedorn and Ryan Neil. A Kickstarter campaign followed, and with the backing of 222 donors from around the world, “In Training” was published.

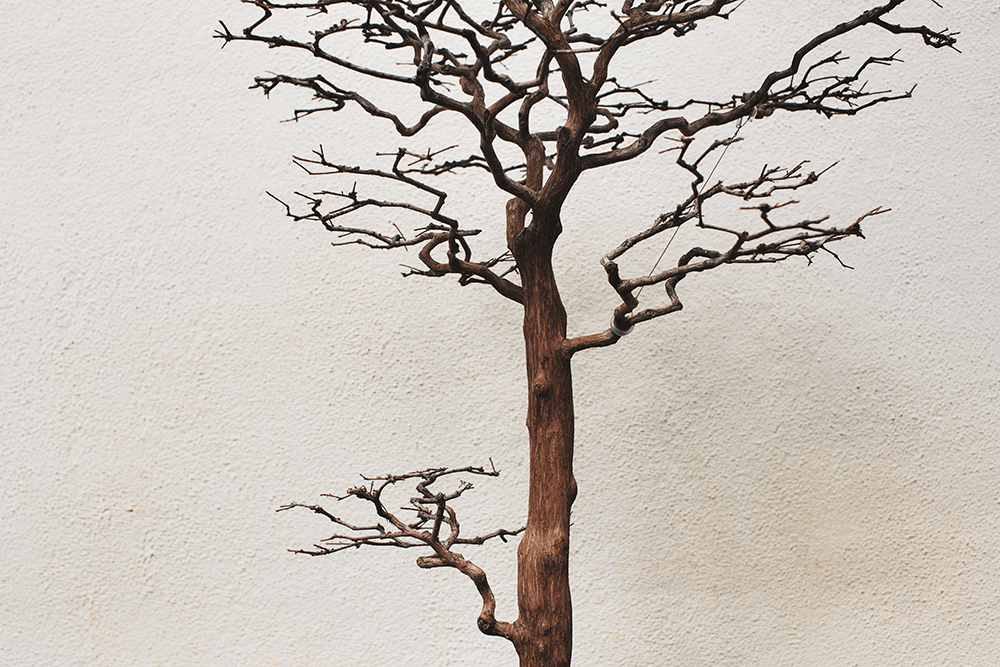

While there are plenty of pictures that show an entire tree in full frame, many provide the experience you might have while walking through the Museum yourself: examining small details of a tree, gazing around the gallery, or even looking down at the mark left by a bonsai pot that has been temporarily removed. Much like the meditative approach that Voss took in capturing the images, paging through “In Training” is an exercise in contemplation – and respect.

Japanese Black Pine, training time unknown. As Voss points out, the curves of the bonsai bear a resemblance to a map of Japan. (photo ©Stephen Voss)

“When I’m standing before a tree, I often think of the many bonsai masters who have tended to it and trained it. For an older tree, there are many generations of people who have worked on a tree and I’m humbled to think of this idea, that they made this their life’s work only to pass it along to someone else after they were gone.

“If I am able to share anything of my time around the bonsai, it is their grace in the passage of time, their peace and the invitation they extend to include oneself in the natural order of things.”

Main Image: Sargent Juniper, in training since 1905 (photo ©Stephen Voss)

For more information about “In Training,” visit bonsaibook.net. You can also purchase a copy on Amazon: bit.ly/TWBonsaiBook

Experience a tea ceremony while wearing kimono at Bonsai Museum