We suspect we’ve found the Japanese god of photography in an impossibly cool 73-year-old strolling through Tokyo in his limited-edition Doc Martens, Leica in hand. Of course, Herbie Yamaguchi, an inspiring, giving, open-hearted photographer with an illustrious career, humbly maintains that he’s not divine. “Maybe the god of photography gave me a special power to become a photographer,” he muses, flipping through his photobooks with us and showing us photos he took of Boy George, Princess Diana and others.

What we can say with certainty is that Yamaguchi is an award-winning photographer, and among the prestigious awards he’s received is a 2011 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Photographic Society of Japan. He’s also been part of competition juries for awards presented by camera giants such as Nikon, Canon and Fujifilm.

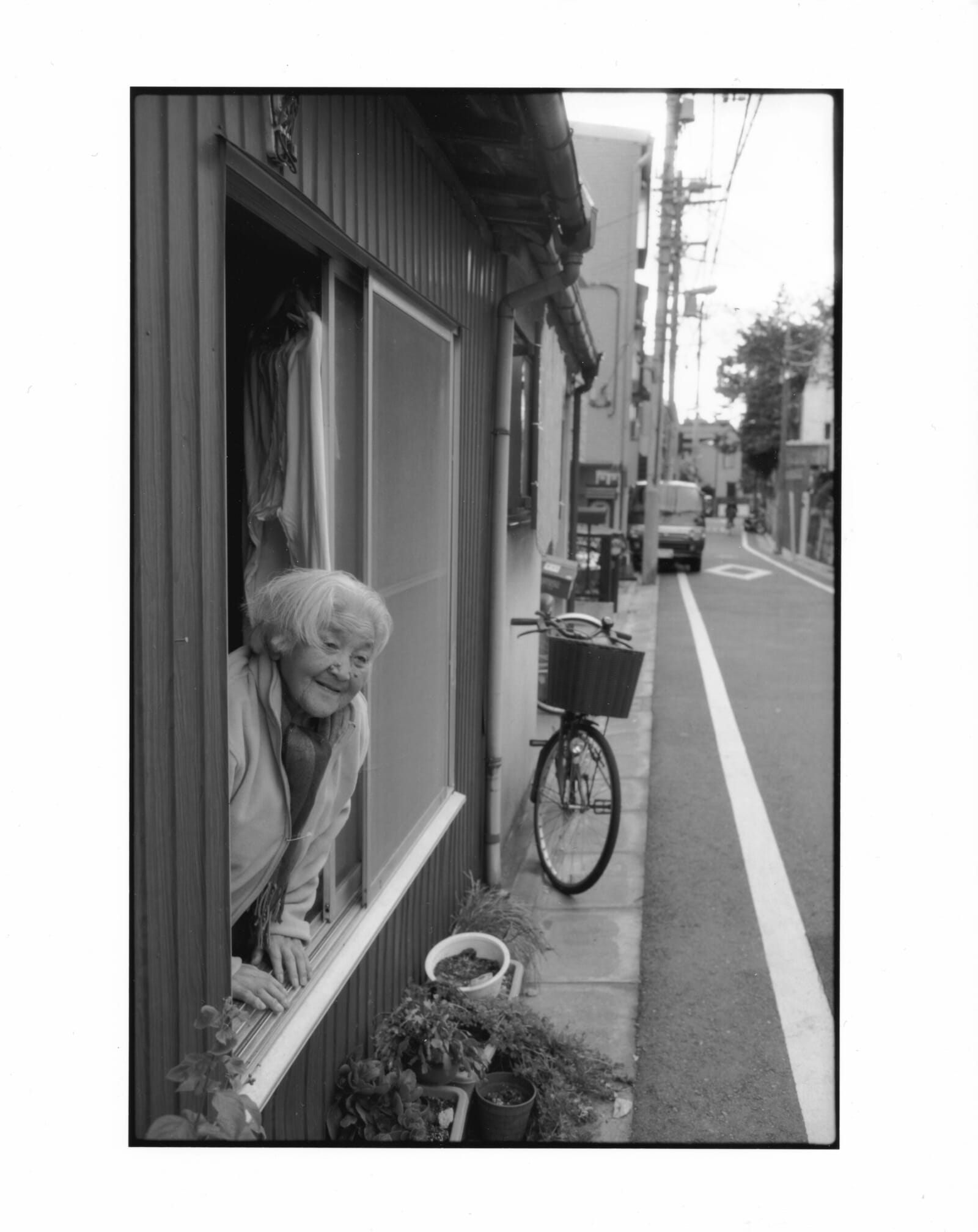

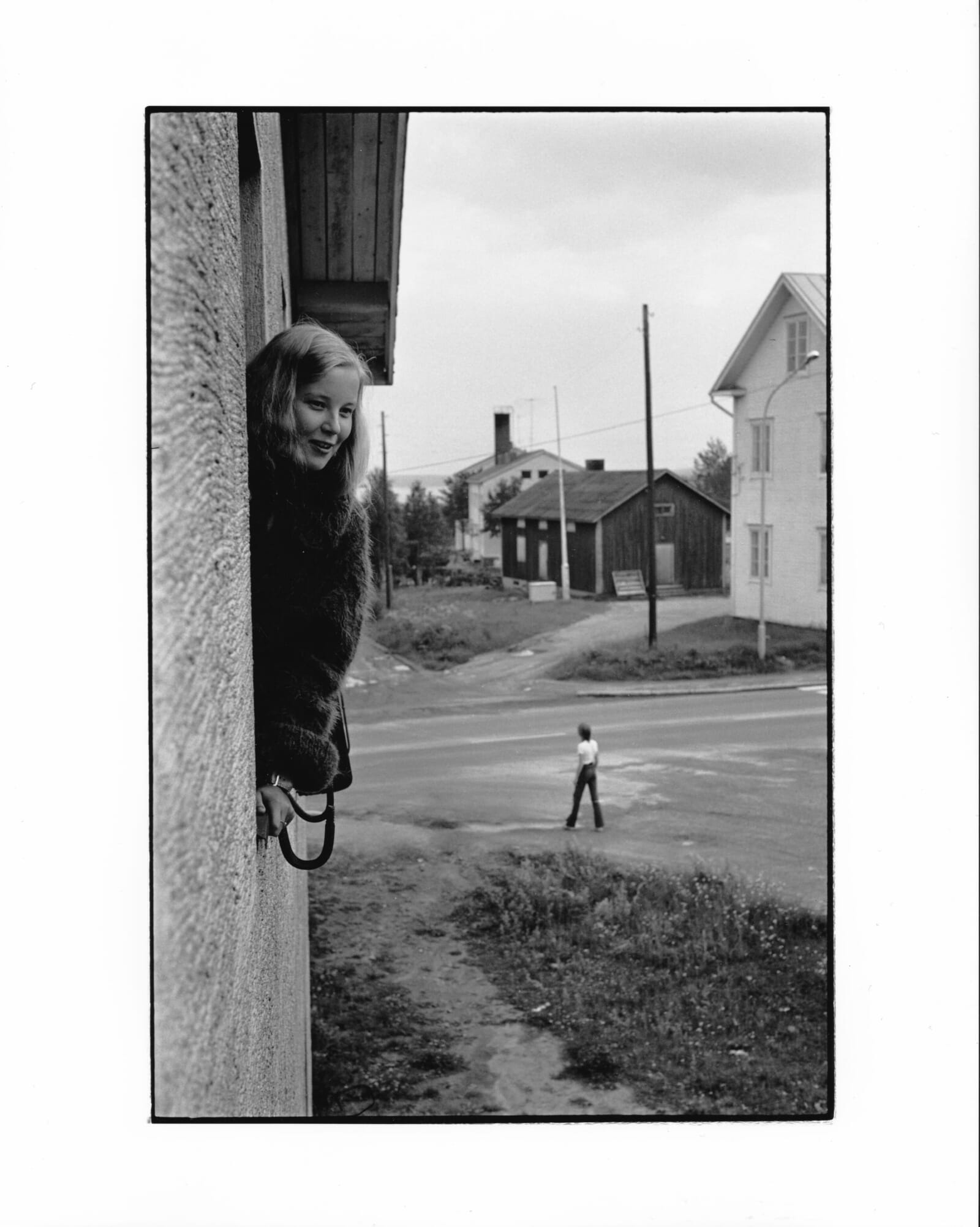

In addition to his photography work, he’s a radio and television personality and essayist and has been a visiting professor at several universities. Above all, he is a man of the people. Indeed, Yamaguchi is fascinated by people, the subject of most of his black-and-white photographs.

People are not only the center of his attention but are intrinsic to his identity as a photographer. “I believe that the day you become a photographer is not the day you buy a camera,” he tells us, “but the day you meet the subject you want to photograph.”

Yamaguchi is specific about his photography, sharing that he likes to take photos that “make people fall in love with people.” He’s been doing just that for half a century. We sat down with him to sift through the past, survey the present and talk about the future.

Photo by Lisa Knight

Snapshots of Hope

“I want to capture human hope.” This has been Yamaguchi’s motto since junior high school when he picked photography as an after-school activity. Suffering from poor health as a child after contracting tuberculosis as a baby, he had been unable to take part in most school sports activities. Photography was his only hope during a dark childhood marked by bullying.

He still remembers the exact moment he realized what kind of photos he wanted to take — those of people full of emotion and care. The memory is rooted in the simple, mundane scene of girls playing with a ball at a local park.

“As I was taking photos, the ball flew toward me, almost hitting me. One of the girls looked at me, her eyes so tender and caring. But I couldn’t take that photo. I had to avoid the ball. Once I was safe, the emotion in her eyes disappeared,” Yamaguchi reminisces. “Those were the first nice, warm eyes directed at me from people in society.” Aside from his parents, he explains, no one had looked at him kindly until that day when he was 20 years old.

“If I could put in a photograph the kind emotion in her eyes, the picture would make everybody on this planet peaceful,” he says. To this day, he chases tender moments like these in his photography.

A few years later, he would photograph another pair of kind eyes — this time on the London Underground — and the experience would change his life as a photographer. The photo was of Joe Strummer, lead singer of The Clash.

“I was hesitant to approach him because it was a private situation,” Yamaguchi tells us. But he gathered the courage to ask for a photo, and Strummer agreed. “I was a stranger, but he looked at me with such tender eyes. He was not his stage persona.”

It’s a photo that was — and still is — highly appreciated. If you search through The Clash photos online, you won’t find another photo of Strummer that radiates such softness. Before he exited the train, Strummer left Yamaguchi with the words that guide him to this day: “Take all the photos you want to take. That’s punk.”

Yamaguchi took it to mean that you should live your life without compromise while avoiding making trouble. He feels that the punk movement was misunderstood and that it was actually about human dignity and being true to yourself.

Joe Strummer from The Clash (London, 1981)

Chasing the Dream

Yamaguchi moved to London in 1973. He had no plan and no English ability but was buoyed by a love of British music and a dream of becoming a professional photographer. As fate favors the brave, Yamaguchi managed to get an acting job despite never having stepped on a stage. He joined a Japanese theater company in London by the name of Red Buddha to support himself and took photos whenever he could. In hindsight, being poor was the catalyst for meeting people, as he had no choice but to share an apartment.

“This guy here, I was sharing a floor with him and maybe five or six people,” Yamaguchi says, showing us one of his photos. “Six months later, he became Boy George of Culture Club.”

Although he shot many recognizable names, he wasn’t actively chasing famous people. Rather, he was just chasing his dream of becoming a photographer, sharing a life, an apartment and a city with people his age who were reaching for their own dreams. Yamaguchi’s photos of these ascending stars, in contrast to photos taken by paparazzi, are full of carefree authenticity, friendship and freedom.

His photo of Princess Diana, too, was taken before she was famous. In fact, Yamaguchi had no idea who she was. His friend said she was someone who seemed important and encouraged Yamaguchi to snap a photo, just in case. At the time, Diana Spencer wasn’t even engaged to Prince Charles. “Just months later, the engagement was announced, and then it was impossible to get near her,” Yamaguchi says. The photo he took is a frozen moment before her life changed.

Diana Spencer (London, 1980)

We can’t be sure that Yamaguchi has superpowers, but the subjects of his photographs have an uncanny way of finding fame not long after being snapped by the photographer — a phenomenon that isn’t limited to his London days when he mingled with talented, driven people in a golden age of sorts. He shares two fairly recent stories with us, both of them taking place in Tokyo and involving complete strangers.

In the first, Yamaguchi was riding on the same train as a pianist. She had no idea who Yamaguchi was, but after some hesitation, she agreed to a photo. After posting the photo on Twitter, she not only went viral but within a year had placed third in an international piano competition in Switzerland.

The second story revolves around a middle-aged taxi driver with a peculiar tuft of forehead hair on a mostly shaved head. A passenger in the back, Yamaguchi couldn’t help but be curious about his driver. He soon discovered that the man had been in a punk band for the last 30 years and had nursed a dream — an impossible one, he thought — to play at the Budokan, a large multipurpose venue.

Yamaguchi took his portrait, then spoke about his encounter with the punk taxi driver on the radio, driving attention to the band. “They played at the Budokan six months later,” he tells us. Perhaps his magic is simply helping people, supporting them and dreaming big together.

The Heart Behind the Lens

Yamaguchi creates a special connection with his subjects, though he cannot explain how. He only feels his heart overcome with excitement when he sees a person in a moment he wants to photograph. “And if they are sensitive enough, they can feel my emotion and accept my camera,” he says. “I think sometimes people look at me through my camera,” he adds. He appreciates their kindness and believes people feel that.

He tells a poignant story about the last photo he took of musician Ryuichi Sakamoto at what was to be his last public appearance before he passed away. Yamaguchi had taken Sakamoto’s photo many times before, but on this occasion, he felt compelled to follow Sakamoto behind the stage and out toward a waiting taxi. The last photo is just Sakamoto’s fingers grazing the door frame as he leaves the building.

“His hand was there for just two seconds. He knew he had cancer, and I felt he was telling me to take a picture. I felt a voice saying, ‘This is the last moment of myself — tell people in the future what kind of person I was.’”

Yamaguchi remembers a similar photo capturing hands that he took of a family reunited after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Showing further still that his heart and camera can truly catch emotion anywhere, during the pandemic, he published a photobook solely of masked people to show how humans can express themselves through their eyes and gestures.

The last shot of Ryuichi Sakamoto (2020)

We Will Be Alright

Yamaguchi has never stopped taking photos. “I take photos every day, and I take my camera everywhere,” he says, then pauses before adding, “Except when taking a bath!” He compares having his Leica in his hand to holding the hand of a loved one.

Fifty years of taking photos inspired his recent “We Will Be Alright” exhibition, which included photos of people separated by decades and continents. In it, he looks at the universal language of love — how people kiss, hug, hold hands, take care of children and talk to friends in the same way, whether it’s 1970s London or 2010s Tokyo.

“Human beings are doing the same thing — loving each other. So let’s be frank, and we’ll be all right,” Yamaguchi says. “And smile a lot. I think especially Japanese people should smile more. Good sleep, good food, exercise and smiling are the most important things.”

Harnessing the negative into a positive is what he recommends to everyone. He muses that if he hadn’t been sick during his childhood, he wouldn’t have taken the photos he has. Similarly, if he hadn’t spent his early adulthood poor and sharing an apartment in London, he wouldn’t have had the opportunity to meet the people he photographed.

He acknowledges that street photography has become more difficult and that people are more reluctant to agree to a photo by a stranger. However, Yamaguchi believes a smile and a pure heart can still go a long way. “And also, if we reject all cameras, we might miss a chance in our life,” he says, hinting at his power to change the lives of those he photographs.

Maybe it’s divine power, a blessing from the god of photography. Or maybe — and, perhaps, more likely — it’s just Yamaguchi’s kind heart clicking happily when meeting other humans.