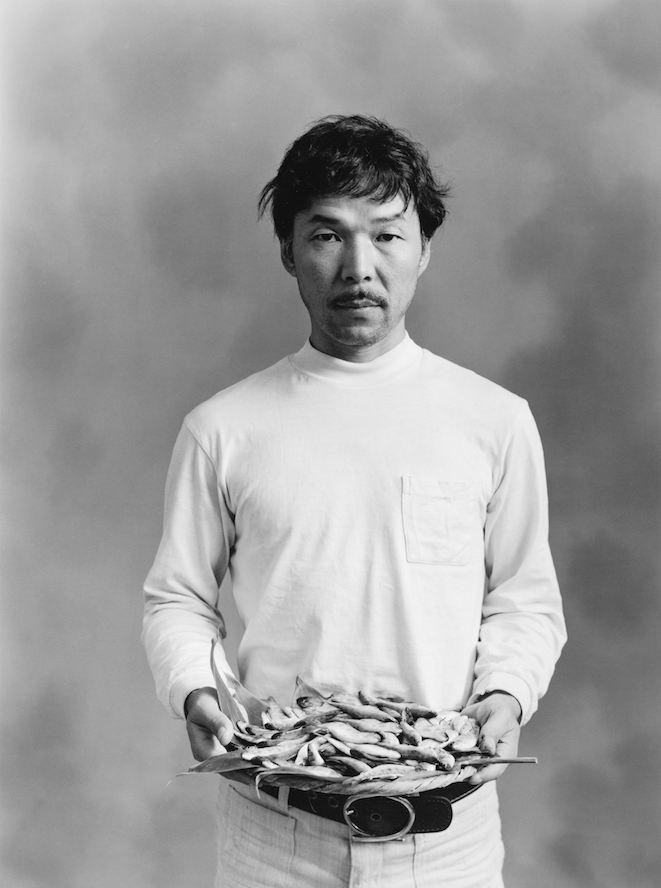

Considered one of the most radical and important Japanese photographers of his generation, the late Masahisa Fukase’s legacy continues to unfold with the republishing of his final photo book.

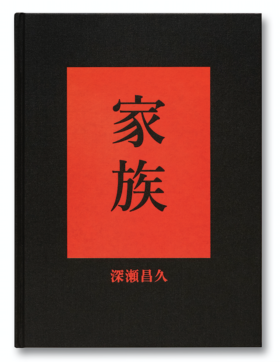

Twenty-eight years after its original publication, Masahisa Fukase’s 1991 photo book, Family, was re-released last month. The book contains a series of idiosyncratic and unconventional family portraits taken at the Fukase family’s photographic studio over several decades. The black and white photos introduce the photographer’s extended family, often including Fukase himself, alongside a cast of half-naked men and women, a pet cat and even the framed memorial portraits of deceased relatives. During the period the photographs were taken, we see the composition of family members fluctuating and eventually dwindling, coinciding with the demise of the family business.

The Fukase Photographic Studio was located in Bifuka, a small town in the remote central northern part of Hokkaido. It was founded in 1908 by Fukase’s grandfather on his mother’s side, and later taken over by his father Sukezo. Born in 1934, two years after his parents’ marriage, Fukase was the obvious heir to the family business and recalls assisting his mother in washing the prints when he was just six years old. At a time when few people had access to cameras, studio photography was thriving and people from Bifuka and neighboring towns would flock to the studio to commemorate their special occasions and events. The family and the business suffered through the turbulent and frugal period of war but recovered in its aftermath.

While attending high school Fukase was given his first camera (a new “portable” model) by his father and subsequently moved to Tokyo to study photography at the Nihon University College of Arts. Upon graduating he found himself more inclined to artistic pursuits and spending time with his then girlfriend; in his own words, “preoccupied” with his personal daily life. He decided to stay in Tokyo where he had begun working at an advertising agency and by default his younger brother, Toshiteru, became the third-generation photographer at the family’s Bifuka studio.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s Fukase experimented with his work, exploring techniques, color and light, and often creating dramatic studies of figures and form, which were at times both playful and powerful. From his early beginnings he used his everyday life and the subjects closest to him as elements and even the focus of his photography. He often featured his partners, notably his second wife Yoko with whom he had a tempestuous relationship, marriage and later divorce. Yoko can be seen in some of the early pictures of the Family portrait series.

Reportedly, Fukase was prone to bouts of depression and the decade following his break-up with Yoko marked a particularly dark period which ended up yielding his most acclaimed book, Ravens, in 1986 (later republished as The Solitude of Ravens). The book remains highly regarded as a masterpiece of modern photography and also marked a shift in process, opening up Fukase’s exploration of isolation, loneliness and occasionally torturous self-scrutiny.

While his career developed in Tokyo and overseas, bringing with it moderate and sporadic attention through the years, he maintained a strong connection with his hometown, regularly making the long journey back to the northern island. It was on these trips returning home, gathering his relatives together with guests he had brought with him from Tokyo (including young actors and dancers), that he had begun utilizing the studio’s old portrait camera to take commemorative pictures in the early seventies and again in the mid-eighties. At the same time he was also capturing the general activities of his family life and chronicling the declining health of his ageing father – these photographs would be collected in the book Memories of Father, published simultaneously with Family in 1991.

Inside the latter, in addition to the unorthodox group shots, we find photographs of the artist himself as well as portraits of his mother and father taken to be used at their funerals after their death. As we view the pictures chronologically throughout the book, we witness the transformation of the family’s patriarch Sukezo, his bare chest and arms shrinking from sinew and muscle to frail skin and bone, until eventually the framed memorial portrait stands in his place.

In some versions of the group portraits we see the posed ensemble facing away from the camera with one or more person turning back or facing the lens. Perhaps we are meant to see only those looking forward as the focus of these pictures or maybe this is simply just another variation of the quirky assembled shots, a parody of the career the photographer himself had rejected.

While the portraits feature numerous extended family members, the entire project can be interpreted as somewhat self-serving in its nature – a family album just for Fukase, cataloging his memories and his mourning.

Fukase’s ex-wife once described him as an egoist devoid of subjective judgment. This is arguably an unsurprisingly common criticism of many gifted artists, but in the case of Fukase it’s particularly interesting that he remained seemingly unconcerned by social, economical and political issues – especially during a time of prolific growth and development in Japan, which inspired so many others. Whether completely self-absorbed or innately tied to his past, his obsession with his most intimate relationships ultimately manifested as work that portrayed life-affirming absurdity and the darkest of emotions.

In 1992, just one year after his counterpoint books were released, Fukase tragically fell down the stairs of his favorite bar, leaving him brain damaged, and he remained incapacitated until his death in 2012. In the years following there has been a revival of interest in the late photographer’s work, with previously unseen archives revealed, new publications and international retrospectives, owing greatly to the foundation of the Masahisa Fukase Archives.

Fukase’s legacy continues and this latest of his republished works finds new resonance in a time where the meaning of the word family continues to be redefined. Family can be viewed as both a celebration and a memorial, inspiring us to reflect on the passing of time and, indeed, on our own relationships. The book serves as a reminder of the ever-changing nature of families, removing the significance of biological links.

Viewed individually, most pages of Family could be looked at purely with the intrigue and curiosity of glimpsing snapshots of someone else’s personal and private affairs, yet presented together as a collection it conjures more complicated emotions. We too can feel the bittersweet sorrow of life and death, longing and distance. We feel sympathy and empathy for the Fukase family, for whom we can’t help but construe a narrative. We enter into contemplation and self-reflection, considering our own blood relatives or chosen family, the memories we share and the impending and inevitable losses to come.

Family by Masahisa Fukase (September 2019) is published by MACK Books and available from www.mackbooks.co.uk and Amazon

Updated On April 26, 2021