Nodoka Odawara is a Miyagi-born sculptor, scholar and critic researching how Japan’s art intersects with its historical narratives. She explores places and their pasts, creating work that examines issues such as state power, public expression, war and gender. At the 2019 Aichi Triennale, she drew attention with an exhibition about a 5-meter arrow that marked the epicenter of the Nagasaki atomic bombing. She earned a doctorate from the University of Tsukuba, and this autumn she will hold a solo show at the Tsunagi Art Museum in Kumamoto Prefecture.

How do you feel about being included in an article series featuring women artists?

Gender is of interest to me. I participated in Gender Balance Hakusho, a volunteer project compiling data on gender equality in the arts in Japan. Its 2022 report found that while there are many young women artists in Japan, they are often unable to continue working long term, and few rise to prominence as they age. Eighty percent of art university professors are male, even though the student body is about 70% female. In art competitions, around 70% of judges are men, and award winners also tend to be about 70% male. Art critics are also overwhelmingly men. The numbers make the gender imbalance in the Japanese art world clear.

Do you think being from Tohoku affects your work?

Very much so. I’m from Sendai, a city with many public sculptures. It’s unusual in that it commissions a new statue each year; they’re installed in accessible places like Jozenji-dori Avenue, where anyone can see them. I don’t think I’d have the same awareness of or interest in sculpture if I’d grown up elsewhere.

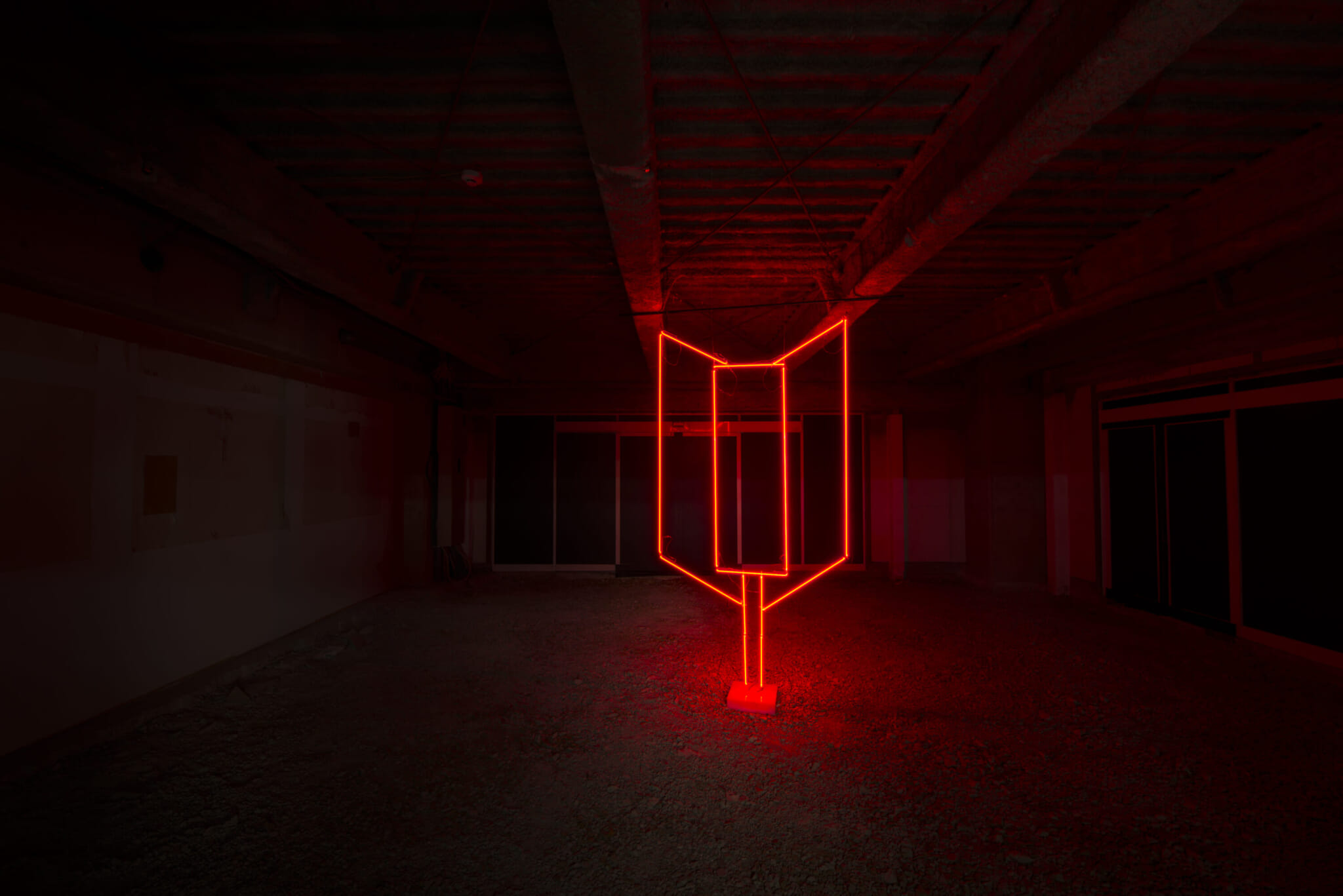

Installation view at Aichi Triennale, 2019 | Photo by Takeshi Hirabayashi

You’ve produced a book and exhibition called “Overcoming/Sculpting Modernity.” What does this title mean to you? How did you adapt the project for your show in Aomori?

I research the historical and social contexts of sculptures, and I contemplate possible alternate paths modern history might have taken. In Aomori, I examined statues such as “Death March in Snow of Hakkoda Mountains (Fifth Infantry Regiment Memorial)” by Ujihiro Okuma, one of modern Japan’s first sculptors, and “The Statue of Maidens Phototype No.1 Group Image” by his contemporary Kotaro Takamura. The first work memorializes the Hakkoda Mountains Incident of 1902, in which nearly 200 people died on a military climbing expedition. On the other side of Mount Hakkoda is Lake Towada, where Takamura’s landmark is located. This was Takamura’s last statue, and the differences in his work and Okuma’s reveal a turning point for Japanese sculpture. Today, Takamura’s Rodin-influenced approach is still prevalent while Okuma’s style has largely been abandoned. In the Aomori exhibit, I also displayed the wooden prostheses of Hakkoda Incident survivors who lost appendages to frostbite. I consider these objects a kind of sculpture, too.

Tohoku’s history sometimes defies common narratives about Japan’s past. How do such complexities inform your work?

After the Great East Japan Earthquake, I wasn’t drawn to Sendai or Miyagi as much as to Nagasaki. There I spoke with atomic bombing survivors, and this was my first time to really hear about what they went through. In school in Tohoku, we weren’t taught much about the civilian experiences of these places.

In Nagasaki, there’s the “Peace Statue” by Seibo Kitamura. I always wondered why this work was placed there as a peace memorial. The artist had also been involved with sculptures that celebrated the war, and it never sat right with me how after Japan’s defeat, Kitamura was chosen to make another work — in the same style — as a tribute to peace.

Nagasaki and Hiroshima have histories of simultaneously being aggressors and victims in war. They’re also home to movements to abolish nuclear power, and they illustrate many of the twists and turns of Japanese history. It’s curious to me how they’ve become places of memorializing peace, and I want to understand how this has happened.

“Overcoming/Sculpting Modernity: Aomori Snow Country Edition,” installation view at Aomori Contemporary Art Centre, 2021-2022

You also write articles and run your publishing company Shoshi Tsukumo. How do these activities influence your sculpture practice?

My work has evolved over time. When I was looking into the Nagasaki arrow, I found that no one had studied it before. I realized that if I didn’t write about it, there’d be no record for the future. I don’t always write to create art, but as I travel, I come across places and events that intrigue me, so I research and document them. This process sometimes results in a sculpture. My life and work feel like a series of chance encounters that have taken me all over — from Sendai to Nagasaki and Tokyo, to Aomori and Minamata. I follow these spontaneous twists, wherever they lead.

Odawara’s next exhibition will be held from September 9, 2023, at the Tsunagi Art Museum. Find out more about Odawara and her works via her website.

Updated On July 10, 2023