Words by Christopher O’Keefe

Amongst the pantheon of great Japanese directors the name Nobuhiko Obayashi does not immediately stand out, and up until a few years ago the man and his work were all but unknown in the west. That all changed in 2009 when his debut feature, 1977’s Hausu, was pulled out of retirement and shown to a packed audience at the New York Asian Film Festival, garnering acclaim and subsequent DVD releases in England and America.

Hausu is a film of frenetic, mad genius. The story of a group of high school girls who go to stay with a peculiar old woman in an ancient house in the country, it is an absolute tour de force of wild, colorful effects and a mash-up of genres. The director is a prolific worker, having steadily released films since his debut, but following the recent success of Hausu it was great to see his latest film, Seven Weeks (No no Nana Nanoka) debut as the closing film of the Yubari Interantional Fantastic Film Festival.

Seven Weeks follows the lives of several members of a family as they gather after the death of the family’s patriarch, Mitsuo Suzuki. Suzuki’s past is recounted by the surviving members as secrets are uncovered and relationships explored. It’s a narratively dense film that explores the complex themes of war-time guilt, the loss of communities and the relationships between the living and the dead through a unique visual style and highly kinetic editing. Like Hausu, it’s an utterly unique film, a truly artistic vision that’s complex, mysterious and fully deserves to be seen.

Obayashi arrived at Yubari on the last day to show his film and I was able to sit down with him the next morning and talk to him about his career. The director carries a dignified kind of cool that certain artistically minded older Japanese men seem to carry off so well. He was open and honest and talked at length about his feelings about his films, art in the movies and the messages he wants to convey.

The main themes of the film seemed to be the effects of the war and also the redevelopment of dying towns. Did you have a personal connection to these themes? Why were they important to you?

I am 66 years old and my generation is the last that has actually been through war. Just like with Hausu we made this film as a message to the people who didn’t know the horrors of war and those hard times. Hausu expressed the atomic bomb for children using extremely childish imagery that they can understand. I made this film to reevaluate the Japanese history since the Pacific War as a whole.

“Economy and politics is all about ‘me, me, me,’ and ‘what I want,’ but when it comes to art it’s about seeing the other person and seeing yourself in them.”

After March 11th and the nuclear disaster I wanted people to rethink post-war history again. I wanted to shoot this film as a documentary, a project of movie journalism. It is purely because of commercialism that there are only two types of movie format: the feature length and short movie. Since [Thomas] Edison we’ve been trying to figure out the possibilities of what movies can do, but after 3/11 I feel like the whole medium of film has lost its power.

So right now, I think I’m trying to break out of this regular format—which I feel is very commercial—and give film the power of free fantasy and make it more deliverable to the people. I decided to create a “movie journal— like “Essays in Idleness” in Japanese literature, which is a collection of information that one sees or hears. I think my film is similar to that art form which is easy to explain, think about and discuss.

Hayao Miyazaki last year released The Wind Rises and it was criticized both here and abroad for the way it tackled the war. Have you seen the film and what did you think?

Well, I know Miyazaki-san and Takahata-san [director of The Tale of Princess Kaguya] and The Wind Rises is the first of his films that I really want to watch but I haven’t seen it yet. I’m really good friends with Takahata and he told me both of these films were very influenced by the events of March 11th. Without this event these films wouldn’t have been made. Princess Kaguya would have been a much shallower, more commercial film but it’s got a lot of substance in it now. To them it’s a very personal film; because of that Ghibli could possibly have gone broke but that was ok with them!

While you’re obviously trying to tell this timely, cautionary tale to the younger generation—how it’s up to them now to rebuild the country—there are also, particularly in the first hour of the film, so many family dynamics at work and generational elements to the story. I wondered how you came about creating that family structure and what your process was developing this complicated family?

Shooting was very similar to 3/11: it was very chaotic. Films are usually shot based on a completed script, but I do it differently: the shooting is very random. It’s almost like making a sculpture and taking out little pieces and then putting them back in. That’s the editing process. But what I do is take that little piece out and put it somewhere else and see what happens, maybe create a little dent and then put it back. The whole process is pretty chaotic and I create this whole chaotic monster and give it to the audience with no explanation and no clarity. I call it a “charming chaos”—I want to communicate with the audience, I want them to find their own way and get them lost first and have them find their own way back.

As part of that process, do you use multiple cameras and improvisation with your actors?

There are four cameras and an extra as a backup. I shoot a whole sequence with no rehearsal at all. There’s a completed script and the actors remember all the lines so that in the performance they become the character. Sometimes weird and surprising words come out and I’ll use that instead of the script. One time takes are the best—I always tell the actors there are no second takes in life.

In that case did you do a lot of rehearsals with the cast? Group work and having them interact as a family unit before shooting?

I noticed that as far as the family dynamic goes in this film, and your others, you seem to focus on women, female characters being thrown into chaotic situations and I wondered to what extent that actually does represent your own interests in terms of the stories you want to tell.

I am old and a man and I was trying to capture the exact opposite, which is female and very young! Young girls are the most charming and mysterious and impossible to understand so by capturing and expressing all those women I’m describing myself. Economy and politics is all about “me, me, me,” and “what I want,” but when it comes to art it’s about seeing the other person and seeing yourself in them: that’s the process of art.

How do you feel about the recent emergence of Hausu abroad, it’s been rediscovered, re-released and film fans are watching it. How do you feel about this?

When I was a child people said that art would only truly be appreciated 100 years after its release, not at the time the artist creates it. Commercialism says that something has to be made right now to make a profit, but just like Takahata and Miyazaki they all feel right now, post 3/11, they have to live as artists. What they make doesn’t have to be appreciated right now and doesn’t need to be understood right now. We are creating art that people in 100 years can appreciate, so even if we don’t make a hit that’s ok. Of course we are capable of making billions and billions of dollars if we follow the rules but that’s not what we are thinking right now: it’s not [about] success, it’s a message how we feel as artists.

But you need a certain amount of commercial success in order to fund future projects … has the recent resurgence of interest in Hausu—and as a result your career—made it easier for you to get your last couple of films made?

Yes, it’s really benefiting my creative work. When I made Hausu obviously it would have been so much easier for me to make a commercially viable film, which would be nominated in first place in a prestigious film magazine, but then I didn’t make that choice. All the adults will say “that’s not a film, that’s not a film,” but the children will appreciate it. The reason I believed in it was because my daughter was seven years old back then and she believed in it (Obayashi’s daughter Chihiro told her father the story of Hausu after having a dream). Thirty years later and my daughter helped me make this film too.

“The younger generations that are watching this film: those eyes will tell it all.”

What’s important was that back then when I was making Hausu it was my future dream, my future prospect. Of course the reality is you have to make a profitable film to keep creating work, but I think the artist should always have this future vision. I believe that this movie, Seven Weeks, will be appreciated in ten—maybe twenty—years. Then that will be the Japanese film standard, I know it. The younger generations that are watching this film: those eyes will tell it all. Kurosawa used to tell me, “I will live until 400 years old, then I can confirm that all my film dreams will come true.” That’s the destiny of the artist. He only lived to 80 years old but his films will live for much longer.

Hausu is a very effects laden film, there are lots of visual tricks, and there’s a sort of similar style in this film too. Are you using the same kind of techniques to do certain visual effects that you did back then?

I believe that film is a creation of science and technology, so I think that movies are a combination of expression and invention … back then when I was working on Hausu I was aiming to make this film the ultimate optical work—that was a very emotional part of the film. Now with this film I tried to do the ultimate digital work, so it’s always invention, invention, invention…

In cinema now, the big issue is the transfer to digital: there’s a lot of talk of this being a huge problem, but as I say, film is an invention; you have to take that for granted. It’s like when film went to sound and then to color and recently to 3D: it’s always a big issue,but what’s important is that what film can do digital cannot do and vice versa. People talk about film disappearing and going digital, but that’s not true! Film has to be preserved because each format is different. So, as I was trying to make the ultimate digital platform, I wasn’t thinking about film at all: I was only thinking of what digital can do.

So now when the younger generation watches my film and thinks, “Oh, I’m going to become like Obayashi and rent digital equipment and expensive stuff!” That’s just wrong. I want to encourage them to think, “I can do this with one pc and one video camera.” I wanted to give hope and encouragement to the younger generation and prove that this is real. Even though we were using four cameras, when something was missing I would pull out my camera phone and keep shooting!

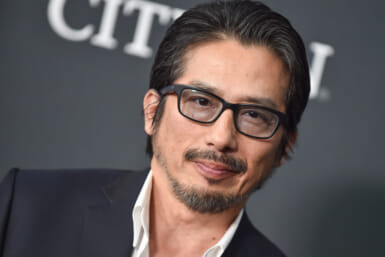

Main Image: Obayashi and actress Miki Jinbo on the set of Hausu, 1977 (OB’s House)

This article was originally published on March 22, 3014