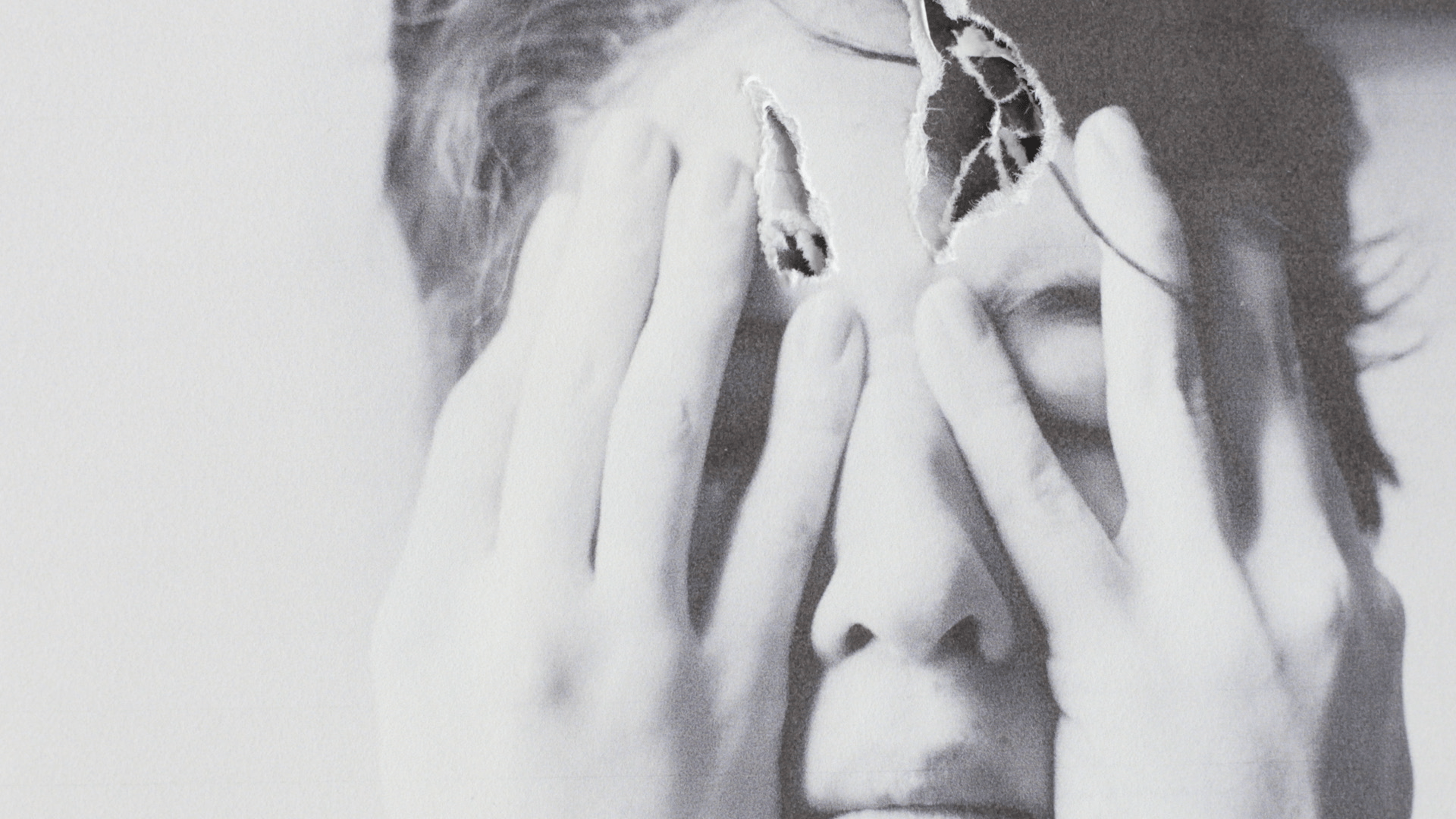

Mixing stop-motion animation and Super 8 video footage, Mizuko (“Water Child”) is a delicate and immersive short film that chronicles a woman’s abortion and the unfolding story of her grief and search for healing. The film focuses on the personal experience of co-director Kira Dane, a Japanese-American filmmaker who narrates the story, taking us on an emotive journey that ebbs and flows from childhood memories in Japan to packed New York subway cars. Through the Buddhist practice of Mizuko Kuyo, a memorial service for those who have experienced an abortion, stillbirth or miscarriage, Dane is led back to rural Japan to conduct her own ritual.

The experimental and atmospheric film offers a tender and thought-provoking perspective on the natural cycle of life and death, also bringing understanding and empathy to a topic so often dismissed as controversial, political or taboo. We caught up with the filmmaker, now living in Nara, to find out more about the film.

Why did you decide to make a film about such a personal experience?

My initial instinct to make Mizuko came from the desire to spread the kind of nuanced thoughts about abortion that I saw in the Buddhist rituals of mizuko kuyo. But the question of how to do that in the strongest way came second. My co-director Katelyn Rebelo and I talked about other options early in the writing process, but in the end, it felt like the most powerful impact would come from telling it through my own voice. It was terrifying and exhausting in a lot of ways.

How was it working together with Katelyn on this film?

We had collaborated on some projects during our time studying filmmaking at New York University. When the idea for Mizuko came along, I knew that I had to bring on a strong outside perspective with a project that’s so personal, or else the process would be too insular. We co-directed, co-produced, co-edited, co-animated, while she was shooting, and I was writing. Katelyn sacrificed a lot to help me tell my story. She was always receptive and understanding, but also stood her ground when the time was right. I think that’s the most important thing in a creative partnership.

What were the benefits of including animation in the film?

The first step was for me to write about my experience with abortion, which would be used for the voiceover and backbone of the film. It became clear to me that the story would need to go to many places in my life, and that I would be speaking English and Japanese, so we needed to use different visual languages. More than abortion, I wanted this to be a project about the arbitrary lines we draw between our minds and our bodies, between our selves and other life. It felt necessary to have different mediums as stylistic representations of how those lines are drawn in a place like New York, compared to in rural Japan. And then breaking down those stylistic boundaries at the end of the film felt like a natural choice.

How was the experience shooting parts of the film in Japan?

A lot of the live-action scenes in Mizuko were filmed in Kamakura, home to some of the most famous Buddhist temples in the country, but also dozens of lesser-known temples and shrines. We traveled from temple to temple on bicycles. The Super 8 camera wasn’t much bigger than a soda can and we carried it, along with a tiny tripod, in one backpack. This spontaneous and low-key way of filming was so preferable to me and Katelyn, after years of NYU film sets where the focus always seemed to be on super high production value and a lot of testosterone. I also had a chance to travel to an incredible mizuko kuyo site on Sado Island in Niigata. I had read about this location in William LaFleur’s book about mizuko kuyo called Liquid Life. There, I finally had the chance to focus on performing my own ritual. The place is called sai no kawara or “the river of souls.” It’s not maintained by anyone but the visitors who go there, inside of a cave nestled in some cliffs right up against the ocean. Along with some personal artifacts, I brought my own mizuko jizo statue, which I made myself out of clay under the guidance of an incredible Buddhist monk in Tokyo. My clay statue wasn’t fired so I left it in this ocean cave knowing that it would eventually weather down into mud and return to the earth.

Do you think people outside of Japan can relate to the practice of mizuko kuyo?

When you think about abortion, you’re thinking about the big human questions, like the origins of life, what we are in relation to other living things, where the separation is between our minds and bodies, what happens when we die… So what does it mean to end a small and separate life that is also merged with your own life? Mizuko was about confronting the different ways these questions are answered in Japanese and American cultures. There’s no denying that most Japanese perspectives on nature and death have been built on the foundations of Buddhism and Shinto, and American perspectives have been built on the foundations of Christianity. Regardless of your personal beliefs, those influences are mixed up in all aspects of the cultures, and they probably define us in ways we can’t even understand. I think it even defines the ways in which people reject religion and spirituality. American atheists are so different from Japanese atheists. A lot of people in Japan are religiously unaffiliated, but if you probe them, you’ll usually find they’re very spiritual. Now a lot of Americans have reached this point where they’re craving a little more spirituality.

How can we encourage more support and empathy surrounding abortion?

Even though mizuko kuyo was formed by and tailored to Japanese culture, I think the thoughts behind it are accessible to everyone. So many Americans are tired of seeing the pro-life versus pro-choice debate in a rigid political context. A political debate is necessary to maintain its legality, but that isn’t getting us anywhere because people feel determined to say abortion is either murder or a normal surgical procedure. For political purposes, it cannot be anything in between. That’s why the nuances of mizuko kuyo have the potential to reach people in the US. It’s admitting to the purposeful ending of a life, and an acknowledgment of the guilt and pain that comes from that. But it’s also acknowledging how very small that life was, as part of a never-ending tide of life, and how often small forms of life all around us are being created and destroyed. I don’t think people should feel like they need to be devoted practitioners of Buddhism to relate to the idea that there are no true barriers between all forms of life. I think what people really gravitate towards is this idea of performing a ritual to heal after a painful experience. There’s a kind of closure that comes from the ritualistic acknowledgment of an experience that you can’t get through speech or writing, because it’s something you’re doing with your mind and your body. More people should feel open to finding their own ways to mourn, regardless of their religious background.

Mizuko continues to be screened at festivals internationally. Find out more about Kira Dane and her work at kiradane.com. For screening venues and other information on the film, check the official website at www.mizukofilm.com or the official Instagram account.

Updated On April 26, 2021