Long before I made my first trip to Japan, I had heard of Nihon no Sankei, this country’s three most famous scenic attractions: Miyajima (or Itsukushima), Matsushima and Ama-no-Hashidate. In fact, an entire chapter in our Naganuma textbook (in Japanese) was devoted to the wonders of the so-called “Scenic Trio,” so we were suitably impressed and concluded that not to hasten to view these marvels of natures handiwork within, say, a month of arrival on those long-denied shores would be to fly in the face of all reason.

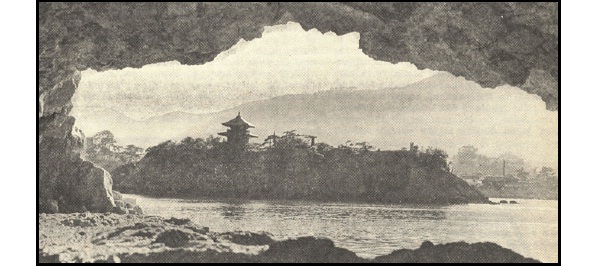

Actually, it took me much longer than one month to see these three places, there having been other charms nearer at hand to distract me, but eventually I did wend my way to their hallowed environs, first going to Miyajima, a small island about 13 miles (or 21 kilometers) from Hiroshima. The principal attraction there is the Itsukushima Shrine and its red-lacquered torii or shrine gate, both of which appear to be floating on the sea when the tide is in.

Next came Matsushima (Pine-Clad Island) near Sendai, north of Tokyo: a bay on which are sprinkled hundreds of pine-covered islets. And finally, Ama-no-Hashidate (The Bridge of Heaven), near Maizuru on the Japan Sea coast, where the Shinto gods Izanagi and Izanami stood while they created the islands of Japan (by plunging their spears into the ocean and letting the drops falling from those spears form the archipelago).

Ama-no-Hashidate is a sand-bar two miles (or 3.2 kilometers) long and 200 feet wide on which stand groves of pines wrought into fantastic gnarled forms by vindictive wintry gales. It is the Japanese custom to climb to a nearby mountain pass named Ochi, turn one’s back to the sand-bar and, bending over, view it from between his legs, thus making it appear to be a bridge hanging in the heavens. Usually there are photographers hovering nearby to take the de rigeur pictures of the visitors bent over in this inane pose, thus providing a lasting momento with which to thrill and inspire posterity.

Having made my dutiful pilgrimage to the last of the Scenic Trio (by then, five or six years had passed), I took myself in hand to ask if the views so obtained had been worth the effort. (Nor had getting there been half the fun, for in those distant days, many roads were a succession of pot-holes going in the same direction while trains were slow, too hot or too cold and unconscionably crowded.)

Replying to this query in the negative, I decided that the Scenic Trio, while lovely and certainly worth a glance or two out of the window if one’s train or car chanced to be passing by, constituted a tourist “course” more attuned to Japanese sensitivities than to ours. To be sure, various facilities have sprung up around these views: inns and hotels, souvenir shops and, perhaps, if one is lucky, even pachinko parlors, not to mention bars, cabarets and restaurants. Still, all in all, the length of time that one can stand still and look steadily at a single view (through his legs?) is limited and not over-long, for most visitors will, like me, feel the urge to press on to other wonders.

Instead of the Scenic Trio, we Westerners who sight-see in Japan have tended more to visit Kyoto, Nara, Nikko, Hakone, Kamakura and even Atami (though to a lesser degree). With good and ample reason, I admit, for there is much to be seen, enjoyed and learned in all of them, to which one must add for consideration that the physical facilities for making the visiting foreigner feel more comfortable and providing him with the conveniences to which he is accustomed do exist there in pleasing forms and quantities, doubtless more so than in the out-of-the-way nooks and crannies of the island chain.

When the first- or even second-time visitor to Japan pushes out into the hinterlands, off the well-trod lanes of tourism, however, he should be prepared for certain possible inconveniences. For instance, there may be no English-language daily available. In their concern over the appearance of his breakfast tray and the manner in which it is delivered and served, the maids in his ryokan (inn) may bring to his room (most inns have no central dining facility) eggs that arc gelid and coffee that is tepid, together with other delicacies, such as bean-curd soup and fermented soybeans, that— while nourishing—arc not exactly what his palate has been accustomed to.

On trains away from the Tokaido and other trunk lines, the announcements of approaching stations may be made only in Japanese, necessitating that the traveler sit tensely hunched forward in his scat, his face glued to the window with eyes straining to read the on-rushing station names (fortunately, in English as well as Japanese) and his luggage all ready in hand so that he may bound off the train during its distressingly brief stops.

Once a young American couple of my acquaintance wrote to me announcing their impending arrival in Tokyo. Although they were to be traveling with their infant daughter, they informed me in their letter — with a firmness of tone that admitted of no debate — that they wanted to savor the true Japan during that, their first visit. Indeed, they wanted to drink Japan to the dregs and therefore from the very moment of their arrival they insisted that everything — repeat, everything — be done in the Japanese fashion, whatever that chanced to be.

Accordingly, I made reservations for them in an inn in Tsukiji and then went to fetch them at the airport in Haneda. The wife was grimly disappointed that I was going to transport them to the inn in my car (a mundane Chevrolet, as I recall) instead of a rickshaw, but I explained that the few rickshaws still in service were used to transport geisha on their evening rounds, to which she countered, with a determined set to her lips, that the three of them simply had to attend a geisha party on their second night in Tokyo and would I be kind enough to make the arrangements.

Slithering out of that obligation adroitly, I delivered them to their inn, which delighted them with what they called its ‘quaint charm.” The next morning, however, they were singing a different tune. Would I quickly make reservations for them in a Western-style hotel? What had gone wrong, I wanted to know. Why, the young wife explained tearfully, the windows had no screens and she could not make the maid understand how she wanted their infant’s formula prepared and the toilets— ugh— they were simply unspeakable! (I hasten to add that in inns without screens, the shutters are closed, mosquito nets are provided and a mosquito-repelling incense is burned through the night.)

There. Now I have done my duty. Even without emphasizing the language barrier. I have made it plain, I hope, that out-of-the-way Japan may not be everybody’s cup of green tea. Those who venture there should gird themselves to expect — not, of course, privation or hardship necessarily — but some differences, shall we say? When he orders a very dry martini in the tiny bar (if there is one) in his inn, he may get a look of utter incomprehension or, at best, a tepid concoction of half Osaka gin and half Kofu vermouth, even though he specified Boodles and Noilly Prat.

For those prepared for such adventures, however, I can heartily recommend out-of-the-way Japan, which has its compensations that are both memorable and soul-pleasing and that have installed permanently in my memory-bank some colorific scenes and adventures that even cruel time cannot degrade to bland pastels.

For instance, I recall a boar-hunting trip I made into the Amagi Mountains of the Izu Peninsula south of Yokohama with a party of American friends. After chasing dogs that were chasing boar up and over those lovely but steep hills all day, we returned foot-sore and exhausted that evening to our inn in Atagawa, on the cast coast of the peninsula, to dine on sukiyaki. After dinner we had one of the maids lead us to the inn’s roten-buro or outdoor bath.

It was a night in November, perhaps the best month of the year in Japan, when the cool hand of autumn is felt but is softened by a palpable sun and clear skies. Above and to our right rose the now-dark shape of the principal peak of the Amagi chain, while to our left and below stretched out the Pacific, upon whose surface dancing lights had begun to appear. These were the lanterns that are hung from the prows of squid-fishing boats to attract those multi-legged aquatics. As we watched, the number of boats doubled, then tripled, until soon there were more than a hundred of them bobbing about on the dark fluid surface.

By then the four of us had settled ourselves in the waters of the outdoor bath and were enjoying the bottles of Kirin beer which I had been blessed with the foresight to order. The bath itself was designed to resemble a natural pool that one might stumble onto in the deep mountains, studded with large rocks and half-hidden by foliage. The hot water of the bath offered a pleasing contrast to the chilly air of early autumn, and the sounds of revelry from within the inn were faint enough to enhance, not diminish, the aura of pleasing relaxation. Bit by bit, I felt myself becoming more and more an integral part of nature instead of a mere intruder.

The mountains and the sea, the moon and the stars, the cool fall evening and the hot spring pool in the midst of the natural foliage made me feel one with them, unconscious of time and enthralled by an insight into what nature and hot springs mean to the Japanese.

Such places as Atagawa abound in out-of-the-way Japan. In the center of Kyushu, for instance, is the spa of Tsuetate, nestled deep in a valley along the banks of a clear frolicsome stream. Behind me was a wintry day and a bleak landscape as my car started down the steep sloping road into the valley, but below me was the fresh greenery of spring. Protected by the walls of the valley from the winds of winter and warmed by numerous hot springs whose steam rose from each inn perched on the stream banks, this secluded village had the appearance to me of Shangri-la, and I dined that evening on delicious trout taken from the stream only minutes before, unfamiliar but tasty vegetable dishes and hot special-grade sake.

Near the town of Minakami, in Gumma Prefecture, is the tiny spa of Yunohana, so isolated that one must catch a train to Minakami, a bus to Takaragawa, walk across a dam and down a road to a pier, and then take a fishing boat across a lovely lake in a trip of indescribable beauty and tranquility. Here one feels that at last he is out of the reach and sound of civilization, as ducks take wing and fish ripple the otherwise placid surface. Leaving the boat, he must again press on afoot for 20 minutes or so before reaching the inn where he will rest: a mountain hut where delicious fish are cooked over an open hearth and only oil lanterns fight the interior at night.

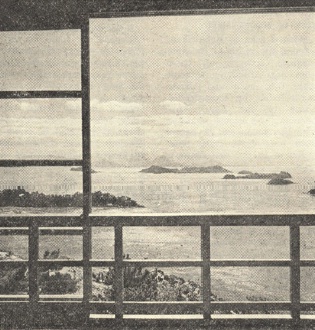

On the Japan Coast, in Toyama Prefecture, is the hot springs resort of Unazuki, its inn standing on the very edge of the Kurobe River that flows through the gorge of the same name between the Tateyama and Shirouma mountain ranges. This is surely one of the world’s most beautiful gorges with cool, green, limpid waters in summer and marvelous colors in autumn and near-by ski slopes for the winter visitor.

The reader will note my frequent reference to onsen or hot springs and to the resorts that build up around them. This is not surprising, considering that there are 13,300 onsen in Japan and that the Japanese regard prolonged immersion in hot water as the most acceptable justification for a relaxing excursion.

The charm of out-of-the-way Japan is not, however, limited to the hot springs resorts, and I can offer as supportive illustrations the Kijima Plateau, an hour from Beppu on the island of Kyushu. Surrounded by the graceful Hyuga Mountains and facing a valley created by a stream of lava from Tsurumidake, Kijima is one of the most restful places in Japan.

There, one will find a small, clean inn whose owner will gladly prepare for the visitor an unforgettable Genghis Khan dinner of excellent mutton on the grass under a 100-year-old tree while spinning him tales of the samurai of long ago. Then there is the coast-line of the Noto Pennisula on the Japan Sea Coast, surely — with its hard, red sand beaches— one of the most arresting and exceptional views in the Orient.

And on north to Sado Island, seldom visited by Westerners: an island inhabited mostly by fisher-folk and farmers who ply their trades in the way their distant ancestors did. It is a simple, rustic way of life, and the visitor won’t find elegant supper clubs or vibrant cabarets with svelte hostesses to soothe (or excite) him. There’s little to do but swim and fish and hike and relax and visit ancient tombs and temples and perhaps contemplate man’s precipitous rush toward folly.

For clear ocean water and assorted aquatic adventures one should consider Amami-Oshima off the southern coast of Kyushu, or Shikinejima, one of the Seven Isles of Izu, or the Amakusa Islands or the Kujuku-to (99 Isles), both off the western shore of Kyushu. Or one of those small inlets along the west coast of the Izu Peninsula, such as Heda and Toi, that can best be reached by the coastal ferry plying between Numazu and Shimoda.

Or Sensuito Island in the Inland Sea, near the Honshu port of Tomoura; a hilly island green with pines and fringed with lovely beaches and a hotel with marvelous views of the island-studded sea, a summer beer garden, a fine seafood menu, and a theater-restaurant whose nightly star attraction (when I was last there) was a genuine Egyptian belly-dancer with a lithe, luscious body and a back-up band from Taiwan.

There must be hundreds of these places tucked away in the fastnesses of the archipelago of Japan. Generally, they are unknown to Western visitors, so the pleasure and peace they offer are enhanced by a sense of exploratory satisfaction, a feeling that you are one of the comparatively few from abroad who has blazed this particular trail.

Added to other charms are the hospitality and courtesy of the residents of these areas, the genuine interest they display in foreigners and their welfare. The people who live in the great cities of industry and commerce, such as Tokyo and Osaka, and in the tourist meccas of Nara and Kyoto have, for the large part, become blase and largely indifferent to the presence of foreigners, and one of us would have to don a leotard of leopard-skin and a polka-dot burnoose to attract much attention. But off the beaten pathways, such is not at all the case. There one meets friendly smiles and eager offers to be of help when needed.

Hie yourself to Sapporo, in Hokkaido, for example, and leisurely walk the streets some mild evening, occasionally dropping in on a comfortable bistro for an ounce or two of encouragement. You will, I think, be gratified at the friendliness you feel there and some of the adventures that may await you, should you reciprocate.

I won’t attempt to provide you here with all the mechanical details of transportation, hotel names, room rates and so forth. Those you can obtain from your travel agent, but I should point out that you may meet some initial resistance at this point. Many of Japan’s travel agents have a mind-set about the preferences of Western visitors and may try to steer you to the Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto (admittedly, worth a visit) instead of a snug little ryokan in, say, Katsuura, on the Pacific side of the Boso Peninsula. But falter not. Persist. In time you will prevail.

In preparation for your trip to out-of-the-way Japan, I recommend one of the following:

1. Find a Japanese friend to accompany you.

2. Hire a guide.

3. Take a two-week crash course in rudimentary Japanese conversation.

If none of these is feasible, don’t lose heart. Instead, make your reservations through the Japan Travel Bureau, buy a guide book (JTB publishes a good one), fill the bottles in your travel-bar and — after pausing for a moment to place yourself in the hands of the patron saint of travelers — fare forth with bold resolve. I believe you will be glad that you did.