by Denny Sargent

Photos by Rebecca Sargent

Well, they’re here. The dearly departed, that is. Welcome to Obon.

From mid-to-late August (or mid-to-late July for those who follow the old lunar calendar), odd happenings can be observed all over Tokyo and environs: drums, dances and songs call disembodied spirits and hordes of black-clad folks make festive graveyard visits. Along with these ritual observances, haunted tales of magic and mayhem that simmer just below the surface of an otherwise placid nation seem to rise from the earth at this time of year. They are conjured up by circles of fire-lit story-tellers, by strange shamic superstitions and by the imaginations of millions of supernatural-loving Japanese.

Obon festival season is a commonly accepted “twilight zone” in Japan that affects almost everyone in some manner. Virtually everyone has some time off in August and a great many people return to their furusato (family homeplace). This ancient festival seems to have been celebrated for longer than anyone can date; it commemorates the time when the “veil between the worlds of living and dead” are parted and one’s ancestors return to earth. In this, it much resembles the ancient western festival of Samahin, now known as Halloween. The difference is that while Halloween is more or less a shadow of what it once was, the celebration of Obon in “modern Japan” still consists of the spirits of the dead being greeted with strange dances and rites.

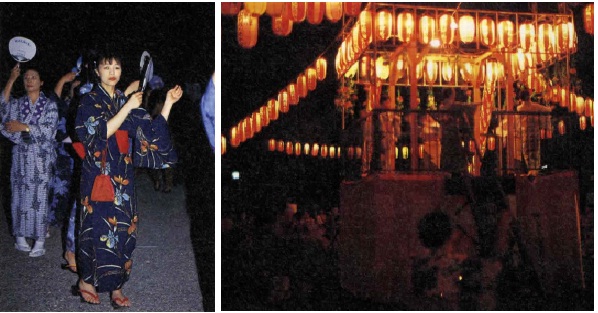

The most famous of these, the circular dance called Bon Odori, is a lively entertainment that conceals an old and spooky ritual. The original object of Bon Odori was to call for the shades of departed relatives so participants could dance with them; this is why everyone dances alone.

It’s very easy to find these dances if you are interested in participating—or just watching. Most neighborhood parks, shrines and temples host Bon Odori for a number of consecutive evenings. You can spot the tell-tale scaffolding, strings of lanterns, drumming platform and festival booths being erected days before. Then join your neighbors in light summertime yukata, grab a fan (uchiwa), put on your geta and follow the sound of the hypnotic drumming.

During Obon, it is also traditional for the family to visit the ancestral haka or grave where usually interred are a large number of relatives. The graves are cleaned and the departed’s favorite sake, cigarettes or food morsels are offered, together with flowers, incense, mikan and sweets. The practice of lighting lanterns to guide the return of the dead is sometimes extended to floating lanterns on lakes or rivers. Thus, Obon is sometimes called “the lantern festival.”

One reason Japanese are so involved with the supernatural is that there is nothing to contradict a belief in these forces in religion. Shinto, the animistic folk religion of the nation, and Buddhism, the long-ago adopted national faith, both accept and propagate a belief in the psychic and occult.

Ancestor worship has been an important part of ancient Japanese thought and the common belief prevails that one’s ancestors—shugorei—constantly watch and guard family members. Obon is the only time the entire nation pauses to honor ancestors.

Most Japanese shrug off ideas concerning religion, but ask about ghosts and frequently you’ll get a different response, not always seriously. Japanese “haunting houses” spring up at festivals and several well-known horror movies involving ghosts are aired on TV.

The mundane and the spiritual often lie side by side in Japan, with moments in which the two meet and mingle. Every torii of every shrine, every magic charm and every supernatural incident announces the entrance to another world, the realm of the spirits, the same dimension from which the ghosts and shades those long dead return at Obon to dance with festival-goers in every Japanese village and city.