One of Japan’s very few major ethnic minorities, the Ainu people have existed (predominantly in Hokkaido) for hundreds of years. However, from around the 18th century, they suffered routine oppression at the hands of the Japanese government. In 1800, the Ainu population was thought to be approximately 80,000. Today, it sits at around an estimated 25,000. The Ainu were recognized as an ethnic minority by Japan’s government in 1991 and then recognized as indigenous people as late as 2008. Despite the systematic assimilation, Ainu culture has endured in Japan to this day. In 2006, Sapporo TV began free, weekly lessons in the language that still run today. There are several cultural facilities dedicated to Ainu culture across Hokkaido and even an Ainu restaurant in Tokyo.

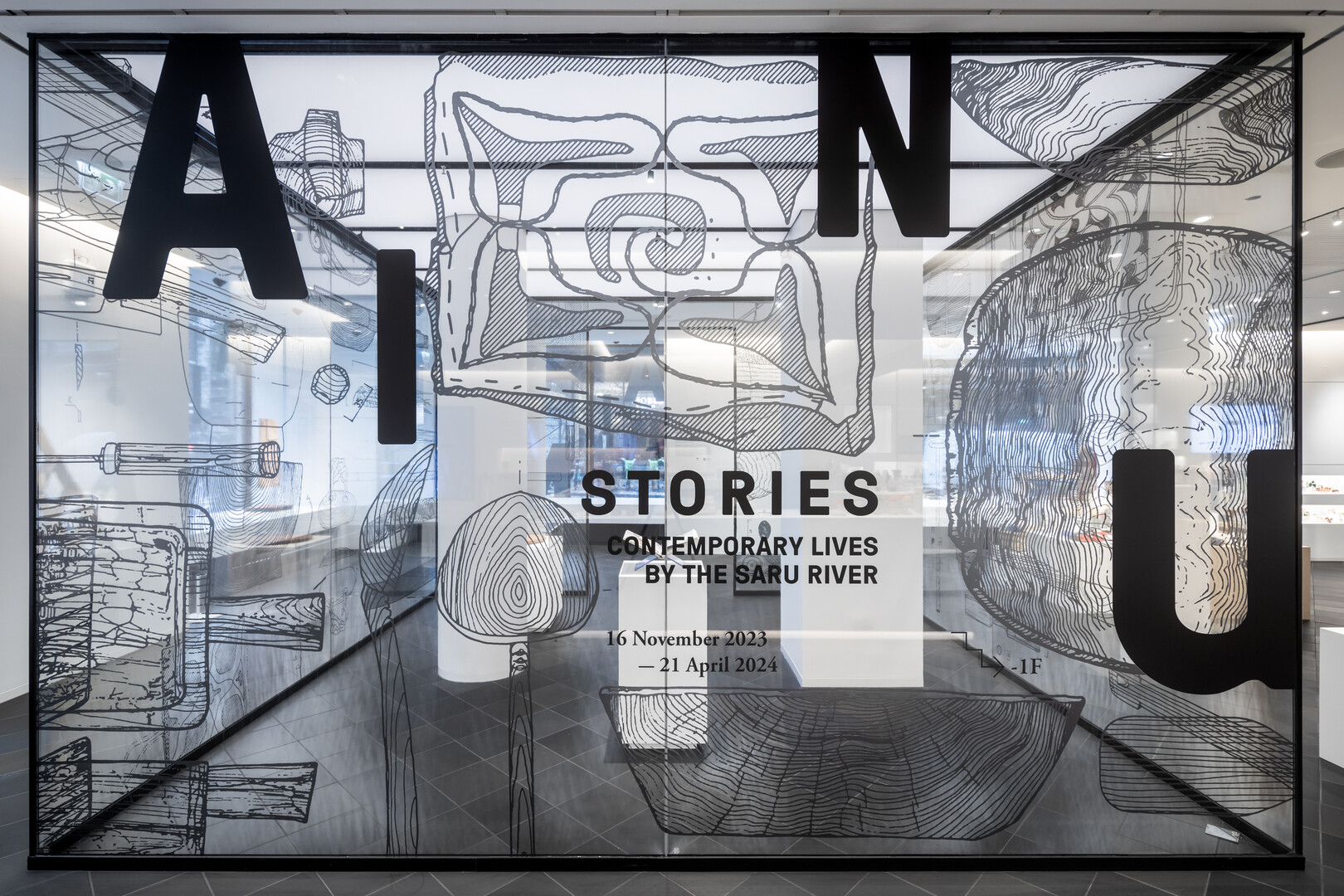

Ainu culture has also recently begun to receive global recognition. In September 2023, Japan House London, a Japanese cultural center in the UK, welcomed Ainu singing duo Ankes (pronounced an-kesh) for an exclusive performance, ahead of the Ainu exhibition, “Ainu Stories: Contemporary Lives by the Saru River.” With the help of Japan House London, I was able to speak with Rino Harada and Seiya Shinmachi, the two performers who make up the Ankes duo, to understand a little more about Ainu culture and what it means to be Ainu today in Japan and beyond.

Photo by Jérémie Souteyrat, courtesy of Japan House London

How Ankes Came to Be

Born and raised in the Nibutani area of Biratori, a town in Hokkaido where 70-80% of the population is of Ainu descent, Harada was brought up surrounded by the Ainu culture. On the other hand, Shinmachi’s relationship with his Ainu heritage growing up was more estranged. He was 17 years old when he first learned of his familial ties with the Ainu people, news that came as a great shock. He explains how the time he spent at university, involved with the Urespa Club, was critical in his journey to determining and understanding his cultural identity.

Loosely translated as “growing together,” the Urespa Club aims to bring together students of Ainu heritage, encouraging them to learn more about Ainu culture. It was in this club at Sapporo University where Harada and Shinmachi reconnected. Although they had been friends as children, the pair lost touch for several years.

Within this community space, the would-be duo uncovered their shared love for both traditional Ainu singing and dancing — a discovery that set them on their shared journey today. They decided to form Ankes in the summer of 2022. Translating to “twilight dawn,” the name Ankes was chosen in the hope that, as the two of them put it, listeners might feel “more energetic” and “motivated to take on challenges” when enjoying their music.

Singing Upopo and Traditional Ainu Dance

Singing and dancing are core to Ainu culture, and a key feature of Ainu festivals. However, Harada and Shinmachi explain that they are not only enacted for performance purposes. While dances and songs are sometimes delivered as an offering to the gods (referred to as kamuy in the Ainu language), singing and dancing are for spectators and performers alike to enjoy, a means of gathering and celebrating. This notion of enjoyment is at the heart of why Harada and Shinmachi decided to form Ankes.

Referred to as “upopo” in the Ainu language, the songs that Harada and Shinmachi sing have been passed down from generation to generation. To prepare for their performances, the duo explain how they listened to sound recordings left by their ancestors, perfecting the versification unique to the Ainu culture. A commitment to faithfully transmitting this ancient way of singing is core to the group’s principles.

Upopo are commonly described as “sitting songs” and they’re sung by several people while beating the lid of a container, called a sintoko. The songs also deploy a technique referred to as “ukou”: they are sung in a round. As you listen, it becomes difficult to distinguish between the parts and determine by whom they are being sung. The melodies are seamlessly woven together, producing a hypnotic quality to the sound.

Upopo are traditionally performed by women, so Shinmachi acknowledges that some audiences might be shocked to witness a man performing the songs. He hopes, however, that his palpable joy might inspire others to also engage in new possibilities and experiences.

Performing Ainu Music Abroad

Harada and Shinmachi express how moving it has been to perform these traditional songs in places previously inhabited by their Ainu predecessors all across Hokkaido, such as Biratori. They speak candidly, though, on the difference between performing in Japan, and their experience performing abroad for the first time at Japan House London.

As a consequence of the traditionally tense relationship between Ainu people and the mainstream Japanese population, the presence of a broader Japanese audience, as they see it, sometimes engenders a greater sense of self-consciousness. By contrast, they note a deeper sense of freedom afforded by the blank canvas of foreign audiences, and express a desire to continue performing in this vein in the future.

Learning the Ainu Language

Harada also spoke about her experience learning the Ainu language, considered an “endangered language” by UNESCO. It’s a journey that only really began in earnest following her time at Sapporo University. She asserts how central she believes the Ainu language is to the culture more broadly, given its deep entanglement to songs, oral literature and anything relating to nature. While she had previously believed herself to be someone without the knack for language learning, she explains how her involvement with “Te Ataarangi,” a Maori language revitalization project, helped her to develop her confidence and skills in learning an indigenous language.

Today, Harada helps to teach the Ainu language as part of an after-school club. With the help of people like Harada, the teaching of the Ainu language is becoming increasingly widespread, with an increasing number of children and adults alike beginning to study the ancestral tongue. The existence of groups like Ankes also plays an important role in both the sustaining and development of Ainu culture for contemporary audiences. With an international debut under their belts, this is only the beginning for the duo, who hope to continue performing in this capacity, spreading awareness and appreciation for a culture that has for too long been ignored.

Related Posts

- Inside Harukor: Tokyo’s Only Ainu Restaurant

- 10 Timelines That Will Change Your Perception of Japanese History

- Sushi Tales: The Surprising History of Salmon in Japan

Updated On February 5, 2024