“It didn’t even have to be cell-cultured meat,” admits Yuki Hanyu. “In 2013, I was thinking about actually doing science fiction and I thought about different options like a Mars colony or interstellar starships and stuff like that. Then I thought it was probably the right time for cell-cultured meat, given the level of technological development in human civilization.”

Hanyu, who holds a Ph.D. in Chemistry from the University of Oxford, is a self-professed otaku — someone with near-obsessive interests in their hobbies, particularly manga and anime. He’s also the founder and CEO of Integriculture (stylized as IntegriCulture), which possesses a bold vision of a future where technically anybody could make their own meat without animal slaughter.

Integriculture’s Culture

The company has almost completed its CulNet® System, which looks like it came straight out of a 1980s sci-fi movie. Cylindrical glass vats of liquid are connected by tubes to a larger vat. These are called the feeder bioreactors that mimic the natural processes within an animal’s body to create CulNet serum, a fluid that contains growth factors for cells, which is then pumped into a larger target product bioreactor. It’s here that the cells grow, producing the protein of the future.

It’s a system that Integriculture claims are pushing cell-cultured meat to a new level. Current conventional methods for lab-grown meat rely on the by-products of animal slaughter. For example, fetal bovine serum is retrieved from calf fetuses that are extracted from slaughtered cows. It’s why the ethics of cell-cultured meat as an alternative protein source have been called into question, and why the products have remained so expensive. By contrast, Integriculture’s process significantly reduces that need, potentially reducing it to zero. And crucially, the company says it can grow cell-cultured meat for just one 60th of the cost of similar products.

The appeal of ethical cell-cultured meat is palpable, considering the damage the meat industry is wreaking on the environment. Meat production alone accounts for nearly 60 percent of global food production-related greenhouse gas emissions. What’s more, 86 percent of crops for livestock aren’t fit for human consumption, highlighting the competition for resources and energy inefficiencies. Cultured meat holds the promise of eliminating the food versus feed debate.

Integriculture insists the concept isn’t just a distant dream, but coming to Tokyo tables soon. It is working on a cultured foie gras, with the aim of launching by the end of 2022.

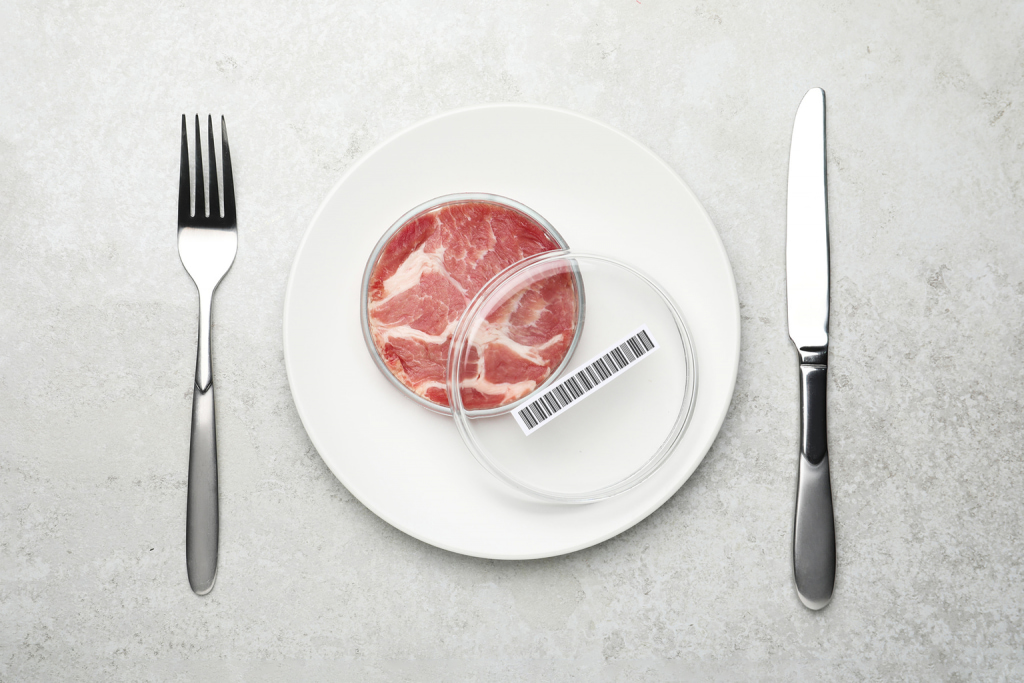

That is, of course, if people are willing to try it. Despite its revolutionary promise, the very image of vat-grown protein is one that makes many people shudder. Hanyu, however, is nonplussed.

“To be honest, until cell-cultured meat becomes cheaper and tastier than existing meat, it will never take off anyway,” he says, with disarming frankness. “So we’re not that worried about the yuck factor. All we have to do is just not disappoint our fans.”

The Start of a Revolution

“Fans” is a key word that underpins Integriculture’s beginnings. The company grew out of the Shojinmeat Project that Hanyu launched in February 2014 as a “DIY open source cell-cultured meat movement.” Fueled by a counterculture spirit, the project envisions a world where young enthusiasts can make meat at home. Indeed, a video showed them doing just that, growing chicken cells and cooking them, alongside step-by-step instructions.

Given that Integriculture emerged from this vision of food democratization, foie gras might seem like an odd choice of product. However, it’s merely a convenient proof of concept, rather than an end goal.

“We are not a cell-cultured meat company; we are a meat-producing machine company,” says Hanyu, keen to stress the point. “Our main product is not cell-cultured meat, but this whole technological platform that allows different players to make different things, including farmers to develop their own meat brand.”

Foie gras is already a high-end item, and so the company has less work to do to bring unit costs in line with current retail prices. Beyond the financial rationale, it’s also creamy, and that means there’s no need to worry about how to give cultured cells some texture.

Research on that front, however, is firming up. Whereas most cell-cultured meat products currently focus on molded meat, mixing the cells with other substances to give the product some bite, Integriculture has partnered with Tokyo Women’s Medical University to work on growing structured steak meat.

Once both taste and texture become customizable, Hanyu envisions a future where meat design enthusiasts, restaurant chefs and local farms create their own “meat recipes,” just like hundreds of ramen stores across Japan that have developed their own specialty broth. By providing the tools for protein production, Integriculture has also strategically positioned itself so that it can tap cellular agriculture startups developing consumer products as its potential clients.

Cultured foie gras. Photo by IntegriCulture Inc.

The Future of Food

It’s a market that’s growing. Startups began proliferating from 2014, and now over 100 companies operate in the space. Investment in cultivated meat companies topped $1.36 billion in 2021, more than doubling the previous cumulative investment in the industry, according to the Good Food Institute, an international nonprofit focused on alternative meat production. It seems investors are banking on a future where plant-based protein doesn’t become the mainstay of our diet.

“Plant-based meat cannot really 100 percent fit into the culinary culture we have,” says Hanyu. “Most of the plant-based meat that is sold today is sold as a packaged processed food, and it’s not something that the conventional meat enthusiast wants.”

Hanyu ends our discussion with a doubt that he will stick, in the long-term, with cultured-cell technology. He ponders working on an artificial womb or ectogenesis, but in the next breath, he mentions spaceships. His goal, however, always remains the same — bringing science fiction into reality.

Learn more about Integriculture at their official website.