She packs her 20-something kilograms of equipment as she takes off to yet another photoshoot: It’s another day, another face, another prefecture somewhere in Japan. But as she heads to meet her model for the day, she has one thought in mind that keeps her going — every scar has its own story waiting to be told.

Facing cancer had become a daily routine for Japanese photographer Hideka Tonomura since a little over a year ago when she first found herself on the receiving end of the bad news: she was diagnosed with cervical cancer at the age of 39 and no doctor could tell her how bad it was until she went through the surgery. “It put me through hell — I was in an appalling emotional state of mind,” she tells Tokyo Weekender in a recent interview. “For someone like me who had always taken excellent care of my uterus, it was an enormous shock.” Uncertain about her future or career, Tonomura underwent a partial uterus removal surgery at a specialized cancer gynecology hospital in Japan where women of all ages — and cancer stages — accompanied each other in their battles against the disease.

A Different Reality

While hospitalized, however, Tonomura witnessed a very different reality. Instead of the defeated faces and disease-stricken people she feared she would see, she saw strong, empowered and determined women putting on lipstick, wearing earrings and cheerfully trying on new wigs while chatting about day-to-day matters. “The sight of this completely mesmerized me — I thought that I had never seen anything so beautiful.”

Days later, the first image that popped up in her mind immediately after waking up from her surgery was a monochrome portrait of the woman lying next to her in the hospital room. Tonomura, who had earlier made up her mind to abandon treatment and the camera altogether if her post-surgery results weren’t promising, took this as a sign that the end was nowhere near. She was no longer leading a battle on her own. She knew that she had to show the world the other side of the cancer reality that she had come to see herself — the women’s resilience, the raw beauty coming from their will to battle the disease.

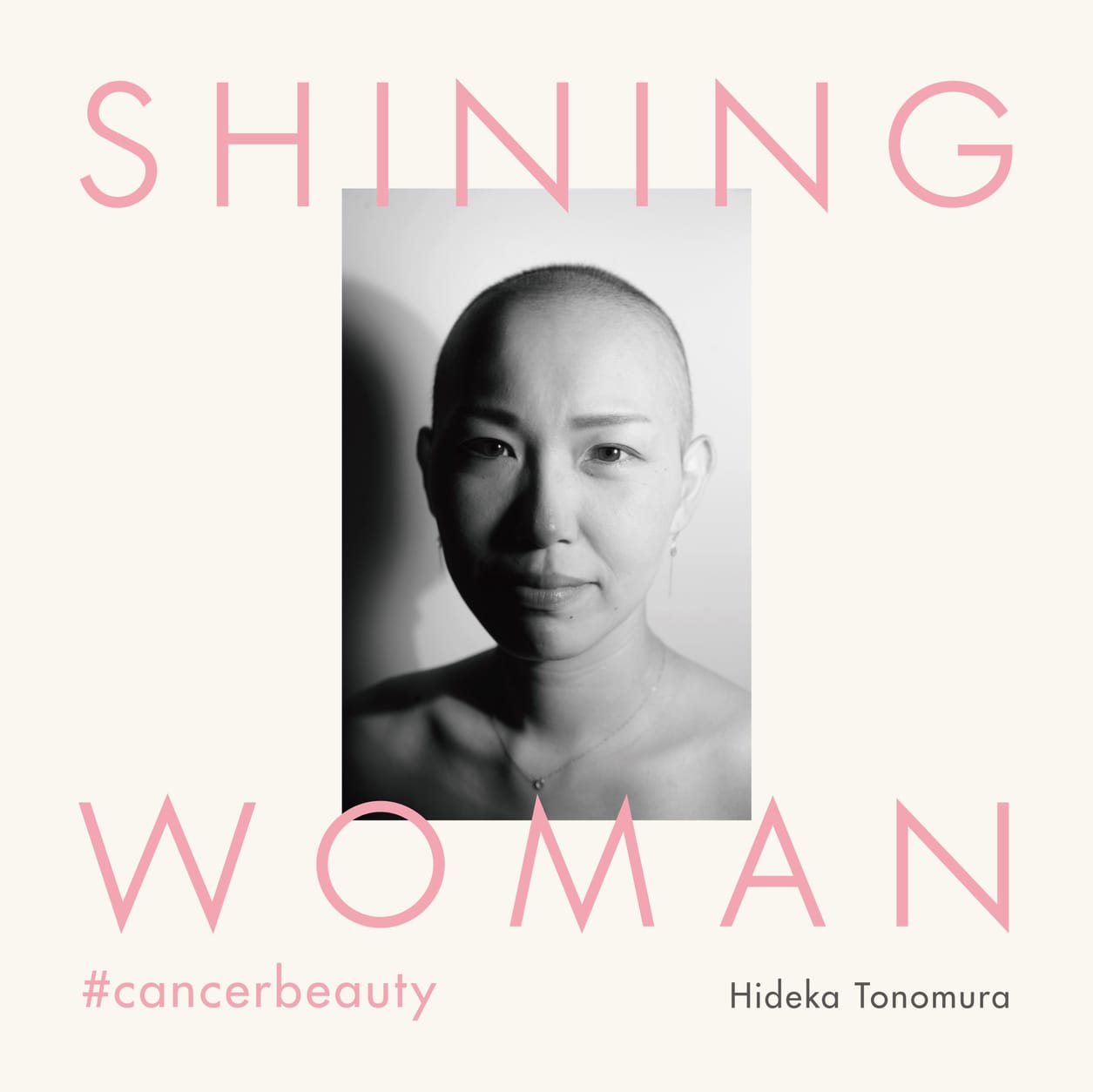

This is how the Shining Woman Project was born.

The Shining Woman Project

Now already in its second year, the Shining Woman Project has documented the living scars of nearly 30 women in Japan who have survived or are battling cancer to help them face and accept the disease. Intending to picture 100 in total, Tonomura travels throughout Japan to meet the women who have reached out to her via the project’s Instagram account, volunteering to participate.

“Being photographed means accepting the wounds and the disease — it’s a sense of getting back what I lost in cancer,” one of the women once told Tonomura. The photo sessions, Tonomura explains, never have a script and it’s up to the women whether they want to pose smiling, show their scars or hide them. “The importance is for them to be who they are and they’re great at it.”

More than an acceptance of the reality, however, by spreading the word through the hashtag #CancerBeauty on social media, the Shining Woman Project is also Tonomura and her models’ silent battle against cancer stigma in Japan: it fights to show that women can coexist with cancer and still be as strong and as beautiful as they’ve ever been. Perhaps even more.

“Despite the constantly rising number of cancer patients, it strikes me that cancer stigma has not risen as a social issue in Japan,” Tonomura notes. “Losing one’s hair, breasts, uterus, and the possibility of becoming a mother, could be devastating for a woman.” While they battle all of this, many women are also forced to undergo invisible verbal abuse and social pressure by being led to hide for the sake of their surroundings. The cases Tonomura encountered through the project were heartbreaking.

“One of the women participating in the project was asked by her boss to wear a wig at work ‘for the sake of male colleagues.’ Another attended her son’s PTA meeting wearing a hat instead of a wig during the hot Japanese summer, while having previously informed the school that she was undergoing chemotherapy. A few days later, she received a circulating school email that read that “there had been insensitive parents wearing hats at school.” For someone who is already striving to hold on the last straw of confidence, incidents like this could have drastic emotional consequences. In Japan, Tonomura says, cancer patients often suffer discrimination during and post-treatment by losing their jobs or facing difficulties returning to society due to their physical appearance. This is particularly alarming for women.

Before her surgery, Tonomura recalls being called in at the nurse room for a one-on-one consultation. “The nurse told me — quite frankly — that she was worried about me. Apparently, I fit in the most alarming group of women — young, alone and dedicated to their looks and career,” Tonomura recalls.

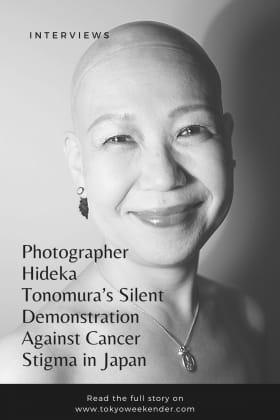

Photographer Hideka Tonomura, the founder of the Shining Woman Project

“She said that women like me often end up either abandoning their treatment completely while waiting for their death, or commit suicide. It got me wondering why we have such limited choices and why society leads us to think that a disease should be a divisive factor in what happens to our future.” The meaning behind the Shining Women Project, Tonomura explains, is all about that — showing that we can coexist with cancer and that if it makes us something, it makes us only stronger. “And more beautiful,” Tonomura adds.

A Catalyst for Change

Every year, Japan sees over 400,000 women diagnosed with cancer. More than half of them survive the battle, despite bearing scars for life. Tonomura hopes that her project can serve as a catalyst to inspire women to stand up for their scars and be proud of their stories — and by doing so, serving as an inspiration for other women who may, at some point of their lives, go through the same difficult path.

“I want the world to become a place where women can live more comfortably so that they can continue to treasure their everyday life and feel free to go outside, without having to experience any verbal abuse just because they have lost their breasts, wombs, ovaries, and hair,” she writes in the introduction to her upcoming photobook Shining Woman. “The true meaning of shining lies in the power with which we fight for our lives.”

When asked what’s next on her agenda, Tonomura smiles and confidently says that, one day, she will make the campaign visible for everyone. “I want to exhibit those women’s portraits in places where everyone can see their powerful and beautiful reality.” “And I also want to tell women to never think of abandoning their treatment — their scars can become someone’s strength.”

Hideka Tonomura’s photobook, Shining Woman, is set for publication by Zen Foto Gallery on October 25, 2020. A photo exhibition of the project will be on display at Zen Foto Gallery in Roppongi, Tokyo, from October 23 through November 21 (tentative schedule. Please confirm the dates via the gallery’s official website at zen-foto.jp/en).

For more information about Tonomura, follow her on Instagram at @hideka_tonomura or visit www.hidekatonomura.com

All photos by: Hideka Tonomura & The Shining Woman Project

Updated On April 26, 2021