As the number of individuals infected with COVID-19 continues to grow so do anxiety levels. Far more than a global health issue, this pandemic is also a social and economic crisis with huge numbers around the globe concerned about their livelihoods. For those already struggling to make ends meet the situation is particularly troubling.

In Japan unemployment and crime rates have remained low for the past decade and it’s therefore easy to assume that things aren’t too bad here. However, scratch beneath the surface and it looks a little different. A significant percentage of those workers in employment (around 40 percent) are on non-regular contracts which means their wages are usually smaller, they don’t receive bonuses and they’re at risk of being laid off at any time.

With the relative poverty rate in this country reported to be around 16 percent, many people were in need of assistance before the pandemic began and things look much worse now. While the ¥100,000 cash handout scheme will provide some relief in the short-term, for a lot of families it won’t be anywhere near enough. Food security is a problem, yet there are few places to turn to for those who require help. At the same time, more than six million tons of edible products are being discarded annually in Japan.

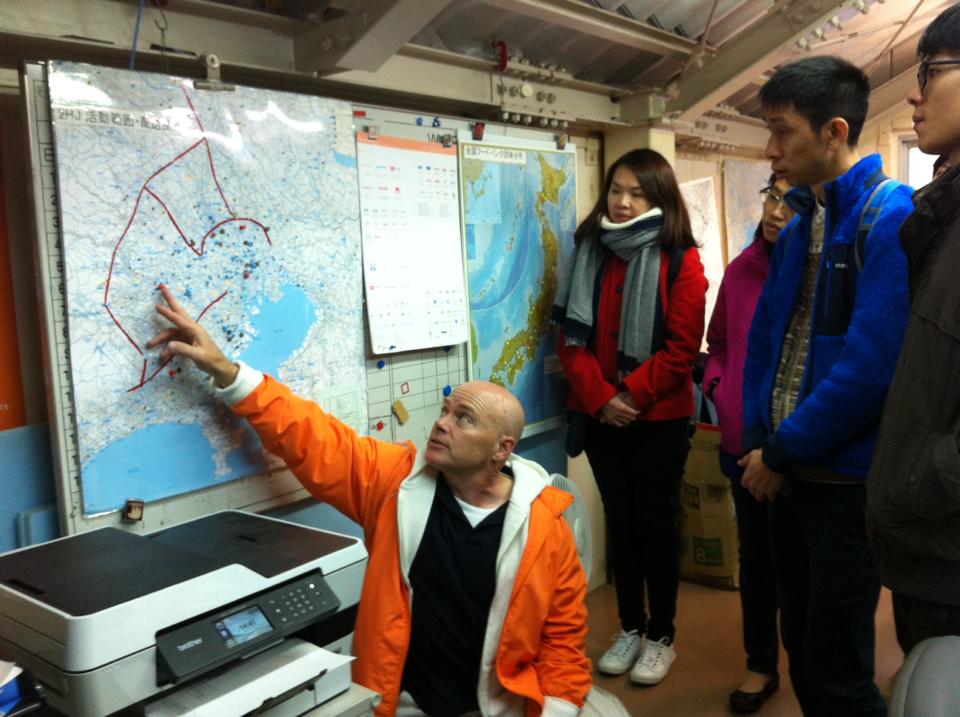

One establishment that is trying to match surplus with need is Second Harvest Japan, the first incorporated nonprofit food bank in this country. Founded in 2002, the organization is led by American Charles E. McJilton who has made a commitment to stay open during the crisis despite the decision by the Abe Administration to declare a nationwide state of emergency.

What impact has the spread of the novel coronavirus had on your operations?

What we’re doing here is what we’ve always done: Collect and distribute food donations to give to welfare institutions, NPOs, faith-based groups, and community organizations as well as directly to those in need. In response to the current crisis we have modified our pantry system (marugohan market) from a shopping experience where users choose what they want to a drive-thru style where a prepared box of food is passed out. Everyone who comes here is registered so if anybody gets sick, we’re able to contact them. Line control is also very important.

What’s included in each bag?

It’s about 10-12 kilos worth of food. There’s some rice, milk, eggs as well as some frozen meat and vegetables. We also send out care packages. They’re a bit bigger and include similar types of items, but there are more canned goods than anything frozen. We’ve seen an increasing number of requests for these boxes from nonprofits and government agencies as many people can’t come down due to the current situation.

Have you seen a significant increase in the number of people picking up food at your pantry?

“I’ve been doing this for around 20 years in this country and never seen anything like it.”

Yes. A year ago, we were handling around 60-70 families on a Saturday which is our busiest day. Recently we are going beyond 200 in a 2-hour period. I’ve been doing this for around 20 years in this country and never seen anything like it. Out of a population of 12 million that may not seem like a huge amount, but you’ve got to remember that the government hasn’t been telling people about us. There are times when I have to tell people we will not be able to serve them. It is really a matter of keeping our pantry safe for our users, volunteers and staff.

What can you do for those who can’t be served?

People can make an appointment for their next visit. With an appointment they don’t need to wait long to receive food and they’re guaranteed we will have something for them. The reservation system helps us control how many people we have in the area in order for us to maintain social distance. In my world, it’s unthinkable to be turning people away. If you had told me that would happen a month or so ago, I wouldn’t have believed you. It’s not because we lack food, it’s a time issue of being able to register new users, registering them for their next visit, and providing them with food. There are a lot of moving parts that go beyond just handing out food.

How much of an effect has the pandemic had on funding?

All of us here realized in February that this would be a tough financial year. 75 percent of our funding comes from corporations and many of them, even by that point, were asking their employees not to go to work. We were ready for it, yet at the same time many companies have reached out and asked how can we help? I’ll give you one example. The president of Seiyu Walmart Japan was on the phone well before the state of emergency was called. After putting a proposal to him, he decided to purchase food worth around ¥10 million for us. Usually you have to go through a long process, but they managed to get things done quickly. Hats off to them.

Do you have enough volunteers?

There’s been a dramatic drop. Before we had around 100-120 volunteers on any given week. That number has decreased by around 60-70 percent. It’s completely understandable. People are naturally concerned about safety. We’ve got a lot of elderly citizens who volunteer here. Their lives are at greater risk. You’ve also got parents who have kids at school worried about spreading infection. There are many things to consider so we’re not at all critical of anyone who says they can’t come in. We just have to get on with it the best we can.

Have you tried to recruit new volunteers?

In a meeting we discussed the possibility of advertising on Facebook but my staff thought it wasn’t a good idea and I understand their rationale. It would sound tone deaf if you have the government telling citizens to stay home and we put an ad up telling people to basically ignore that request. Informally, we do say, if you feel safe, we could certainly use you. Another issue is that the work isn’t straightforward. It’s not just chopping vegetables in a kitchen. You have to interact with people in a chaotic environment. For anyone doing it for the first time there needs to be some kind of learning curve to figure things out.

How have you been coping with the situation?

“In many ways this is harder than 3/11 because it’s an ongoing disaster.”

By staying humble, keeping things in perspective, and finding a reason to laugh. My son was born on April 11 and I had planned on taking paternity leave. That’s no longer possible. My staff are very capable, but there are certain decisions that only I can make. Around two hours after my son was born, for the first time in my career I had to tell people we didn’t have food for them. That was tough. In this role you have to make those decisions. For instance, if someone doesn’t have ID, we can’t give them food. Safety is paramount. In many ways this is harder than 3/11 because it’s an ongoing disaster. There’s a big risk that people could get sick.

What can people do to help at this time?

We are always hugely appreciative of any food or money that people provide. If they can’t do that, just dropping us a line to show solidarity and support, that means so much to us. We see ourselves as a public asset that is serving the community. This is a food bank for everyone. Also, once things have calmed down it would be great for people to come over to see marugohan market. It’s like a small supermarket where people can shop for around 30 kilos of food in 30 days. We then ask them to give back to society in some way. That service is frozen at the moment; however, people can continue with their membership when things get back to normal.

For more information about Second Harvest, visit: 2hj.org/english/

About marugohan market: marugohan.jp