Parliament is close to allowing the uber popular homesharing service to continue operating legally in Japan – with a few restrictions.

Airbnb is a perfect example of a disruptive technology: the company’s $31 billion valuation means that some of its value is coming at a cost to hotels and hotel booking sites alike. But these old industry are not going gently into the overnight: in San Francisco, the city where Airbnb first started opening doors, the nine-year-old behemoth has been forced to confront serious legal obstacles (just as the other big member of the disruptive duo in the new sharing economy, Uber), and it has been legally challenged in plenty of other cities and countries as well.

But this legal wrangling wouldn’t be happening unless the company happened to be a runaway success, and like it is around the world, Airbnb is proving to be a hit in Japan for tourists, Airbnb Hosts, and marketers alike – the country’s penchant for creative design has led to some really creative spaces, the service is putting up record numbers in Japan, and for a quick minute, your mom and dad had a chance of kipping for a night atop of Tokyo Tower through Airbnb.

But developments over the last year have put Airbnb on tenuous footing in the Land of the Rising Sun. Even though finding hotel rooms in Japan can be tough during popular times of year (hanami season, anyone?), more and more tourists are coming to Japan, and even more are on their way with the 2019 Rugby World Cup and the 2020 Olympics on the way, hotel owners and their lobbyists aren’t so keen on being disrupted. That’s one of the reasons behind the regulations that were proposed by the Abe administration last year regarding these kinds of properties, which were designated as minpaku (home sharing). Under the recommendations, minpaku hosts would only be allowed to house guests who were staying for one week or longer – which is a good bit longer than average Airbnb stays around the world. Failure to comply with these rules would be illegal and could mean a hefty fine.

Ota Ward in Tokyo adopted the proposal shortly after it was announced, and the city of Osaka joined on in April. For most of the rest of the year, the situation looked grim for the company that had seen 500 percent growth in 2015. When interviewed last year by Forbes, Airbnb Japan Country Manager Yasuyuki Tanabe voiced his frustration, saying that “the government should create new laws specifically for the sharing economy, rather than employing a modified version of lodging rules that are almost 70 years old.” Although there might be creative solutions to deal with these new restrictions – booking for seven days but only requiring that a renter stay for three or four – some would-be Airbnb hosts decided to pursue different options.

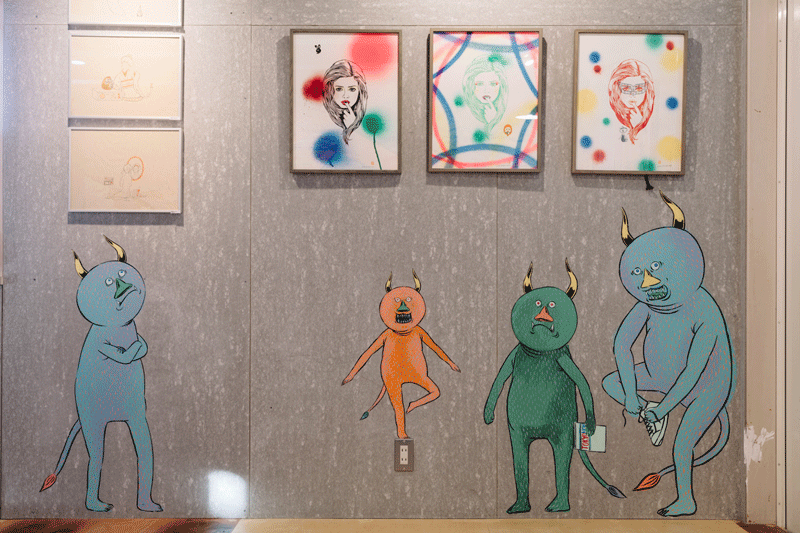

For example, the BnA space in Koenji (as well as other locations around Japan), which features rooms decorated with pieces by local artists – who also receive some of the revenue from the operations – launched a test room as an Airbnb property, but chose to continue the project with official hotel licenses. As Yu Tazawa, founder and COO of BnA explains, “this is because we believe being compliant to the regulations to make sure the rooms are operational for a long time is our responsibility to the participating artists, since they will receive a revenue share as long as we operate the rooms.” He admits that his personal feelings about the issue and his perspective as a business owner are somewhat at odds: “I personally believe de-regulation is the way to go for Japan overall, but as a company that spends a good amount of resources following the regulations, the end of illegal minpaku could potentially be beneficial to our business, and thus to the artists we support.”

Fortunately for Airbnb, tourists looking to stay in affordable or interesting kinds of lodging, and the host of Hosts that have sprung up around Japan, the new proposal put forward by the Abe administration should have people sleeping a little easier. According to the proposal, which has been submitted to Parliament and would go into effect in 2018, minpaku operators will be required to notify their municipal government about their business, and they will be allowed to lodge guests for 180 days a year. Hosts will be held responsible for any disturbances created by their temporary tenants, and local governments would have the authority to decrease the total number of days that minpaku could host guests, if complaints are raised by people in the community.

Markus Leach, who runs the Reef Break Retreat in Chiba, was positive about the proposal, but felt that the 180 day limitation was impractical and counterproductive: “Just last week I saw an article about the acute shortage of accommodation in Kyoto and the need to add 6,000 guest rooms to the total currently operating. Sites like Airbnb could help close that gap so any limitations seem ill advised. However, the hotel lobby is very strong in Japan and from the tax perspective I can see why the government would want to see proper registration. But why limit registered minpaku to only 180 days, other than to make things difficult for non-residents to run these businesses? This seems self-defeating, considering the critical accommodation crisis that Japan faces.

“I think the 180 day limit is a mistake, but the other terms are not unreasonable. Why should registered hotels and ryokans pay tax while many Airbnb owners don’t? That said, if I were operating in an area where the local government could reduce the number of acceptable booking days further, due to complaints, I’d be nervous. The sight of ‘gaijins’ in their neighborhoods will no doubt result in many, often unfounded, complaints in urban neighborhoods.”

Tanabe, in an official statement following the announcement of the proposal last week, took a more measured tone: “We welcome the news that the Cabinet has taken steps towards rules for short-term rentals that are fair and progressive, while reflecting Japan’s unique needs. The opportunity to share your extra space brings benefits to countless communities in Japan, and we look forward to continuously working with the government to promote a responsible and sustainable framework for short-term rentals and home sharing across the country.”