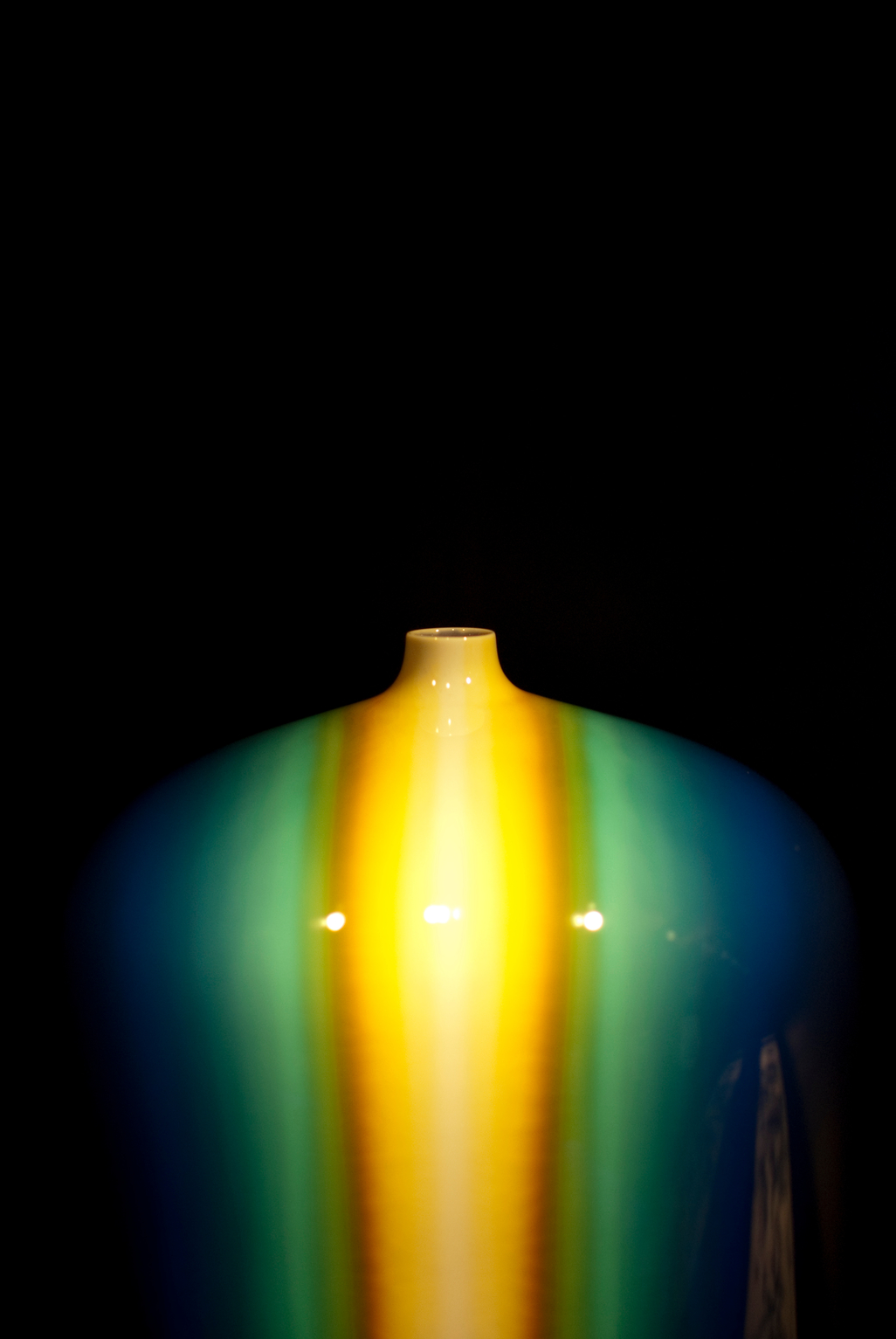

Kutani ware is a style of fine porcelain pottery developed in Kutani, Ishikawa Prefecture over 350 years ago. The porcelain is famed for its elegant designs, characterized by the use of exceptionally vivid colors, made possible by the firing process.

History of Kutani Ware

Ko-Kutani Ware

Kutani ware was first produced in 1655 in the city of Kaga, Ishikawa Prefecture, by Toshiharu Maeda and Saijiro Goto. It is believed to have used a similar porcelain to Arita ware.

From its inception, Kutani ware was distinguishable thanks to the use of over-glaze painting which produced strikingly vivid colors.

Created with Japanese porcelain, Kutani ware pieces made the most of the material’s flexible qualities, teasing out vases and tea sets into wafer-thin shapes. Kutani ware got its name due to the original kiln being located in Kutani, Ishikawa. Just 50 years after production began, however, it suddenly stopped. For around a century, Kutani ware from 1705 onwards is impossible to find as the kiln disappeared, and no-one is sure exactly why.

Products created prior to 1705 are known as ko-kutani (old kutani) ware.

Shoza wine cups

Kutani Revival (Saiko Kutani)

Just over 100 years later, in 1807, Aoki Mokubei, who moved to Kutani from Kyoto, began producing Kasugayama Kiln. He was a well-known painter and established the Mokubei-fu Kutani ware style.

Other, smaller kilns followed until there was finally a turning point in 1824. A rich merchant named Denemon Toyoda founded the Yoshidaya Kiln (named after his trade name) with the aim of reviving Kutani ware. He was supported by the shogunate at the time and established the kiln very close to the site of the lost production plant in Kutani.

Two years after Yoshidaya Kiln opened, it was moved to the nearby town of Yamashiro, due to the troublesome weather conditions of Kutani. Sadly, due to financial pressures, it closed just seven years after its inception. Uemon Miyamotoya, who’d been the on-site manager at Yoshidaya Kiln, eventually took over and reopened the facility.

Tokuda Yasokichi III | Photo by Ariya Stock via Shutterstock.com

A New Phase of Yoshidaya

While it was originally built to restore the older Kutani ware (known as Ko-Kutani) style, the Yoshidaya-Miyamotoya Kiln developed its own signature style in the process. This became known as Yoshidaya-fu. It soon became renowned across the country for the high quality of its signature four-color glazes.

When Miyamotoya passed away in 1845, the kiln began to fall into disrepair. Wazen Eiraku, a craftsman from Kyoto, was called upon to help revive its fortunes, developing Eiraku-fu in the process.

Following the fall of the shogunate and start of the Meiji Period, Kutani Ware was exhibited for the first time in Vienna in 1873. It was a hit and began to receive significant attention from the West and Europe in particular. Kutani ware quickly became an in-demand product, and the original kiln started to prosper.

Until 1940, it was made at the original site of the Yoshidaya Kiln. The porcelain evolved, developing different styles and individual Kutani artists became prominent.

Artists such as Tokuda Yasokichi III and Minori Yoshida were bestowed with the titles “National Living Treasures” thanks to their work modernizing the traditional Kutani ware styles.

How is Kutani Made?

Kutani is made from white China clay from Komatsu. The purified clay is shaped by the potter and then fired once. Next, an underglaze is applied, along with a white glaze, which turns it translucent and almost glass-like after firing. The white glaze helps to strengthen the porcelain piece. The ceramic is then fired once more.

In true Kutani style, after the second firing, the piece is painted with colorful overglaze. It is fired again, and the colors mix with the glaze, turning vivid and bright.

After this step, it’s ready for its gold or silver leaf application. Once the gold or silver has been applied and the top glaze added, the piece is fired for the final time.

How to Identify Kutani Ware

There are several different types of Kutani ware.

The characteristics of the pottery are generally defined as being made of thin porcelain and being glazed with a combination of yellow, green, purple, red and Prussian blue colors. Below we have included some of the most common styles.

On the underside of the pieces is the Kutani signature, normally painted on as porcelain marks.

Aote

Aote was popularized by the Yoshidaya Kiln. In Aote, four colors are used. Red is omitted leaving the Prussian blue as the most striking.

Iroe

Iroe is the most colorful of the Kutani styles, with five different colors used: yellow, green, red, purple and Prussian blue.

Eiraku

Akae

The Akae style was popularized by the Iidaya Kiln. Red is the predominant color.

Eiraku

Eiraku style is characterized by its use of red and gold, in striking patterns.

Shozo

Shozo is perhaps the most common of the modern Kutani styles. Developed once trading with the West had begun in earnest, Shozo makes use of several different styles, including somewhat elaborate shapes and color combinations. This was to appeal to their growing European customer base.

Updated On February 13, 2023