On this day (August 20) 10 years ago, Mika Yamamoto and her boyfriend and colleague Kazutaka Sato were travelling in a van with the Free Syrian Army in Aleppo, Syria’s second biggest city. The couple were covering the civil war in the area for Nippon TV when they were suddenly caught in the middle of an armed conflict between Syrian opposition and pro-government forces. Yamamoto was shot in the neck. Tragically, her death was confirmed at a nearby hospital shortly after. She was just 45.

“Mika was greatly respected among journalists because she pursued a real mission. If only her name was more widely known during her life. Sadly, it is her death that has made her a national figure,” Yamamoto’s friend and fellow news correspondent Miyuki Hokugou told Time magazine. So, who was this heroic reporter who regularly risked her life to provide news coverage in war zones? In this month’s Spotlight we look back at the life of Yamamoto, one of Japan’s bravest news journalists.

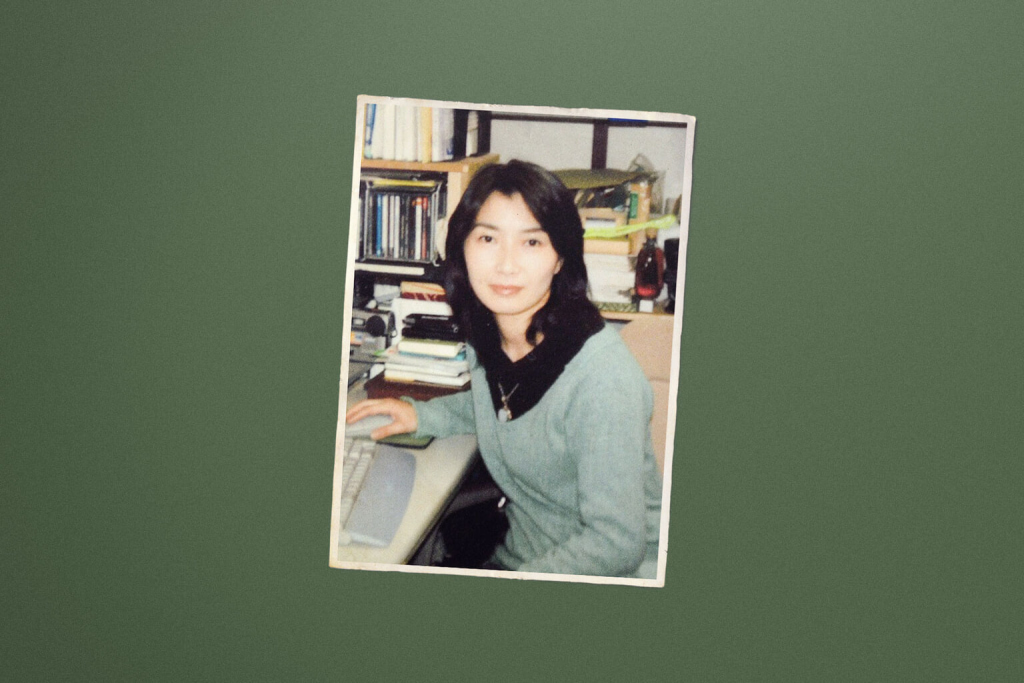

Yamamoto wanted to give a voice to suppressed females inside Afghanistan | COPYRIGHT (C) JessicaGirvan/Shutterstock

Background

Born in Tsuru, Yamanashi Prefecture on May 26, 1967, Yamamoto was the second of her parents’ three daughters. Her father was a journalist for the Asahi Shimbun and from a young age she was determined to follow him down a similar career path. And so she did, joining the Asahi Newstar as a reporter in 1990. A talented video journalist and director for documentaries and news programs, it wasn’t long before Yamamoto was attracting interest from other media outlets.

In 1996, she joined the Japan Press, an independent media group based in Tokyo. This was when her career as a war correspondent began. From the mid-1990s onwards, Yamamoto reported on the front line in regions such as Bosnia, Kosovo and Chechnya. Using her handheld camera, she did more than simply describe what was happening. Her aim was to give a voice to people that were often ignored, particularly women and children.

A subject she was particularly passionate about was the suppression of females inside Afghanistan. Yamamoto first visited the Islamic country in 1996 and continued going back annually, even after the US invasion in 2001. “I asked myself what issues there were that few people covered, which needed to be communicated but were not given enough attention, and what locations were very difficult for people to get to, which needed to be covered and reported on but weren’t,” she once said at a lecture at Waseda University.

Yamamoto was in the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad when it was attacked in 2003 | COPYRIGHT (C) Rasool Ali/Shutterstock

A Dangerous Profession

The courageous journalist was aware of the risks involved in her job. She was contracted by Japan Press to cover war zones for major publications and TV networks that weren’t prepared to send their own full-time staff because of the dangers associated with the work. Prior to her death, the scariest moment came in April 2003, when she was staying at the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad, Iraq.

It was the building in which most of the foreign media in the city were based. American forces fired a tank shell that hit the 15th floor balcony of the hotel being used by Reuters. The news agency’s Ukrainian-born photographer Taras Protsyuk and Spanish cameraman Jose Couso of Telecinco television were killed in the attack. The two soldiers concerned, Sergeant Shawn Gibson and Captain Philip Wolford said they believed they were firing on enemy troops.

Yamamoto was in the adjacent room to the one that was hit. She quickly rushed next door to see what was happening and to check on the injured. In the immediate aftermath of the shelling her voice can be heard frantically crying out for help. On the same day, Al-Jazeera’s media station on the other side of the river from the Palestine Hotel was also hit by American forces. Reporter Tareq Ayoub died as a result.

Yamamoto set off to Tohoku soon after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami | COPYRIGHT (C) FLY_AND_DIVE/SHUTTERSTOCK

Recognition and Reporting on Forgotten Victims

In 2004, Yamamoto was awarded the Vaughn-Uyeda Memorial International Journalistic Prize for her coverage of the war in Iraq. Named in honor of former United Press Vice President Miles W. Vaughn and Sekizo Uyeda, former president of Dentsu advertising agency, it’s conferred annually on journalists “who’ve made exceptional contributions to the promotion of international understanding through their reporting.”

Given her extensive experiences in war-ravaged regions, it was then no surprise Yamamoto was selected to be a guest lecturer at Waseda University’s journalism school and her Alma mater, Tsuru University. According to Waseda Professor Shiro Segawa, she was “a person who excelled not only as a journalist, but also as an educator.” Settling for a life in the classroom, though, was never an option. She felt it was her duty to be out there, at the forefront of the action, reporting on forgotten victims.

Nine days after the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011, she set off to Ishinomaki, Kesennuma and Miyako to interview people affected by the disaster. “News media throughout Japan were using every possible means to gather and report information, but there were still places that were abandoned, areas that were isolated,” she said. “So, I thought I’d gather information to fill in those gaps.”

Yamamoto’s Death and Legacy

Another major news event in March 2011 was the start of the Syrian civil war. Bashar al-Assad’s government faced an unprecedented challenge to its authority with demonstrations taking place nationwide. Police, military and paramilitary forces suppressed the protests with violence. This soon expanded into a fully-fledged war. Yamamoto and her partner Sato were sent to cover the conflict for Nippon TV. It was an assignment that would ultimately lead to her death.

On that fateful day on August 20, 2012, Sato remembers 10 to 15 men walking towards them. “At first I thought it was the Free Syrian Army and we were on the same side, so I held up my camera and started shooting,” he told CNN. “It was then that it happened. I thought I was going to be hit and that’s when I was separated from Mika… I need to know what happened to her. Mika was the best part of my professional and personal life. She was my right hand, my left hand, my everything. I have no idea what to do now she’s no longer here.”

Yamamoto was the fourth foreign journalist killed in the Syrian War and the first from Japan. On May 3, 2013, she was posthumously awarded the World Press Freedom Hero prize by the International Press Institute. The Mika Yamamoto International Journalist Award was also established in her honor. It is presented annually to individuals working in journalism (whether through video, picture or print) who exemplify her spirit.