During the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), if you weren’t a samurai, farmer, craftsperson, merchant, or priest, they didn’t consider you a human in Japan. The bulk of the people outside those social classes were classified as “hinin,” which literally translates to “non-human.” This caste of outcasts included such people as vagrants, beggars, prison guards, some gatekeepers, entertainers of all kind and often the disabled. With the only exception being blind people and their guild of blind bankers.

Musical Beginnings

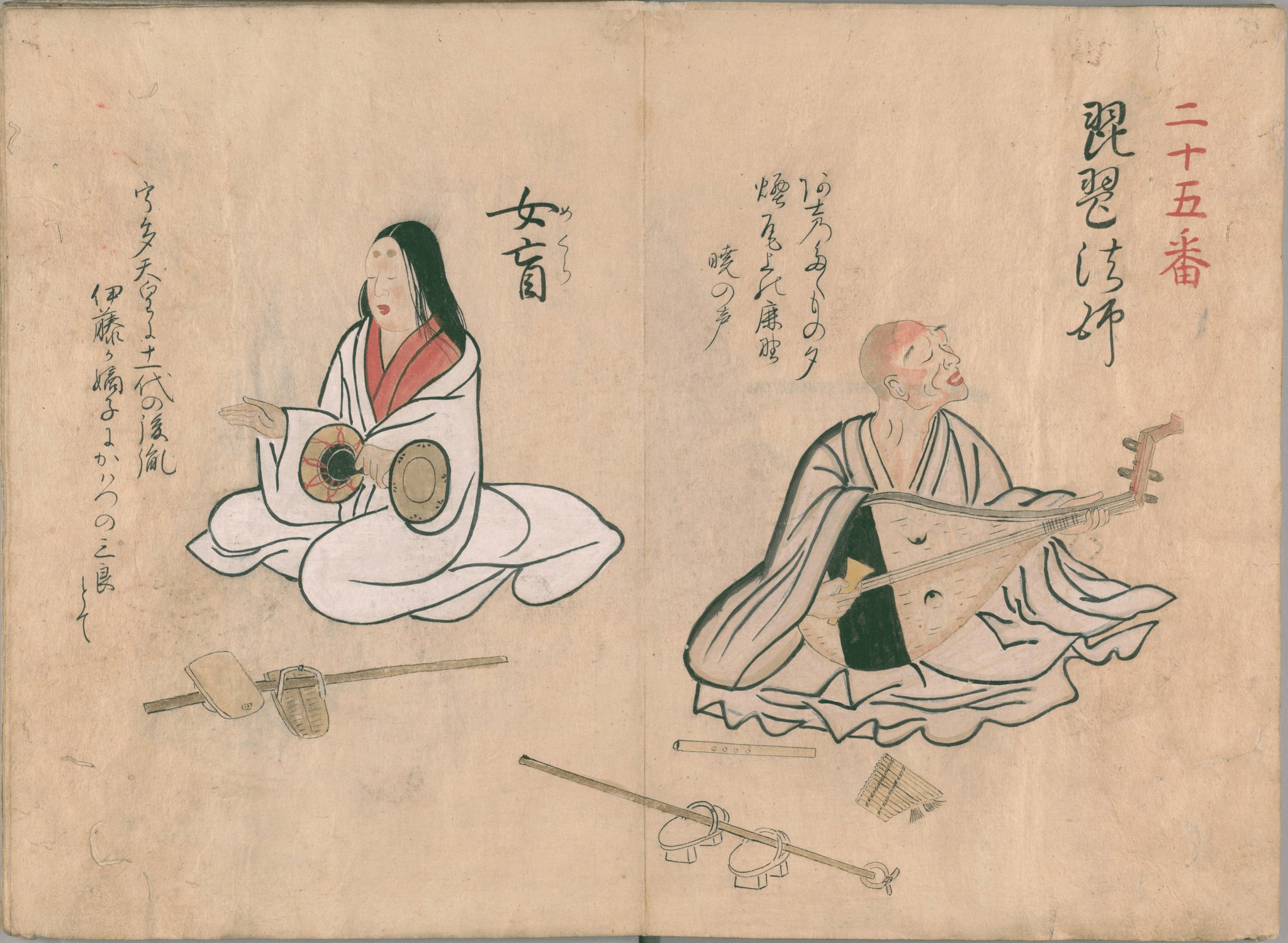

The visually impaired have long held a special place in Japanese society, going back to the 14th century when The Tale of the Heike was first composed. It was an epic account of the Genpei War between the Taira and Minamoto clans and was recited with musical accompaniment on the biwa (a Japanese lute). The traveling storytellers of The Tale of the Heike, known as the Heike Zato, were all blind men who actually won a government-approved monopoly on publicly performing this piece thanks to the Todoza.

The Todoza, meaning “the guild of our way” and often simply called “the Blind Guild” by Western sources, was a type of support group for blind men whose membership dues got them perks such as the aforementioned right to perform The Tale of the Heike. The government initially authorized that as a form of welfare, so Japan’s blind population would have a way to support themselves. The guild and its members soon found other sources of income. They gained a kind of unofficial monopoly on performing massages, acupuncture and playing other types of instruments. Then, during the Edo Period, the Blind Guild started lending money to rich merchants and samurai.

Friends in High Places

The fact that the Todoza was allowed to become a bank is astonishing. Though Japan was still a feudal, rigidly hierarchical society during the Edo Period, it was one that was slowly starting to adopt capitalist practices. Lending money became a huge business, but it was reserved for a select group from the merchant class. The hinin class was barred doing so. But, as stated earlier, blind people were not categorized as non-humans, even though people in very similar positions like street performers and actors were. How did they manage to swing that?

A Japanese woman is massaged by a blind Japanese masseur. Colored photograph (between 1890 and 1899). Image from Welcome Library, UK.

Since their creation, the Heike Zato were connected to the royal court and powerful families in some form or another. They initially enjoyed patronage from the Minamoto clan, one of the key players in The Tale of the Heike. The Todoza also loved circulating legends about how blind biwa players were supposedly first taught to play the instrument by a blind Imperial prince back in the ninth century. In later years, the Todoza affiliated itself with the aristocratic Koga clan, so they could claim exemptions from some government edicts.

The Todoza Played Both Musical Instruments and the System

During the Edo Period, the Tokugawa shoguns ruled Japan. However, they were technically servants of the emperor. By then, he was a figurehead with no real power. Thanks to their connection to the imperial court, the Todoza successfully argued that they were answering to a higher authority than the Edo shogunate and were thus exempt from their caste classifications. This not only allowed them to become bankers but also gave them immunity from the occasional government debt amnesty.

Biwa-hoshi in 71-Shokunin Uta-awase-Emaki (71 Artisan Poetry Contest Picture Scroll). Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Edo officials oversaw all civil court disputes in the city, especially when it came to monetary matters like unpaid loans. However, at the time, Edo was one of the largest cities in the world and the court system occasionally got overwhelmed. So, from time to time, officials would issue “figure it out among yourselves” edicts, which forced all plaintiffs to settle their disputes privately. If you were a samurai who owed a lot of money to a merchant, this usually meant you no longer owed a lot of money to a merchant. Here’s the really interesting part: the Blind Guild was exempt from these amnesties.

There was no way to escape a Todoza debt. If you failed to pay, members of the guild would stand in front of your home hurling obscenities your way and telling everyone who would listen that you were a deadbeat.

Honor was and still is a big part of Japanese society. Hence, the shaming tactic often worked but it did not earn the Todoza a lot of friends. That said, it did earn them a lot of money. Since they were immune from the debt amnesties, many other moneylenders would lend cash through the Blind Guild as a form of insurance. For that, the Todoza charged a fee.

Blind Hate for the Blind Bankers

Over time, the Blind Guild made so much money, they basically became the Bling Guild. Unfortunately, they were a bit too successful. Edo was periodically swept by movements lamenting that no one knew their place anymore in the strictly hierarchical Japanese society. This, in turn, caused the government to occasionally crack down on those who managed to get a leg up on the samurai.

The Blind Guild was once accused of taking away a samurai’s honor because he fled the city to escape a massive debt he owed them. It was also around this time that Edo started seeing the appearance of “medical” texts claiming that blindness was the result of immoral behavior.

In the late 18th century, many members of the Todoza were arrested. Some were banished, some were fined, while others were executed. The Guild mostly lost momentum after that, eventually being disbanded during the Meiji Restoration.

Ukiyo-e print by Hokusai. Image from Welcome Library, UK.

Going Forward

However, while the Blind Guild is no more, its legacy lives on to this day in the form of the Zenshinshikai, a national association for blind acupuncturists. Today, about 30 percent of Japan’s roughly 90,000 licensed acupuncturists are visually impaired, making them a separate and distinct group within the profession.

Of course, nowadays, blind people have access to all sorts of vocations and are especially active in Japan’s farming sector. But a not-insignificant number of them also act as custodians of a traditional Japanese profession that, centuries ago, gave the blind some advantages in a world that might not have called them “non-human” but very often treated them as such.

Japan’s history is full of fascinating stories. Here are some more to read: