On this day in 2019 Japan lost one of its most prominent international figures. Known as the “diminutive giant,” Sadako Ogata became the first-ever female UN High Commissioner for Refugees in 1991. The Cold War had just ended, but within weeks of taking up her new position, the Tokyo-native had to deal with one of the biggest crises of the decade as more than one million Iraqi Kurds fled to Iran and Turkey.

That was just the beginning. During her tenure, Ogata witnessed the regional conflicts that followed the fall of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union as well as the Rwandan genocide. Her focus, however, was always on the humanitarian needs of refugees rather than any political bargaining. When she first took on the role, many were skeptical about this small, self-effacing Japanese woman’s ability to run such a huge humanitarian organization. By the end of her reign nine years later, nobody doubted her.

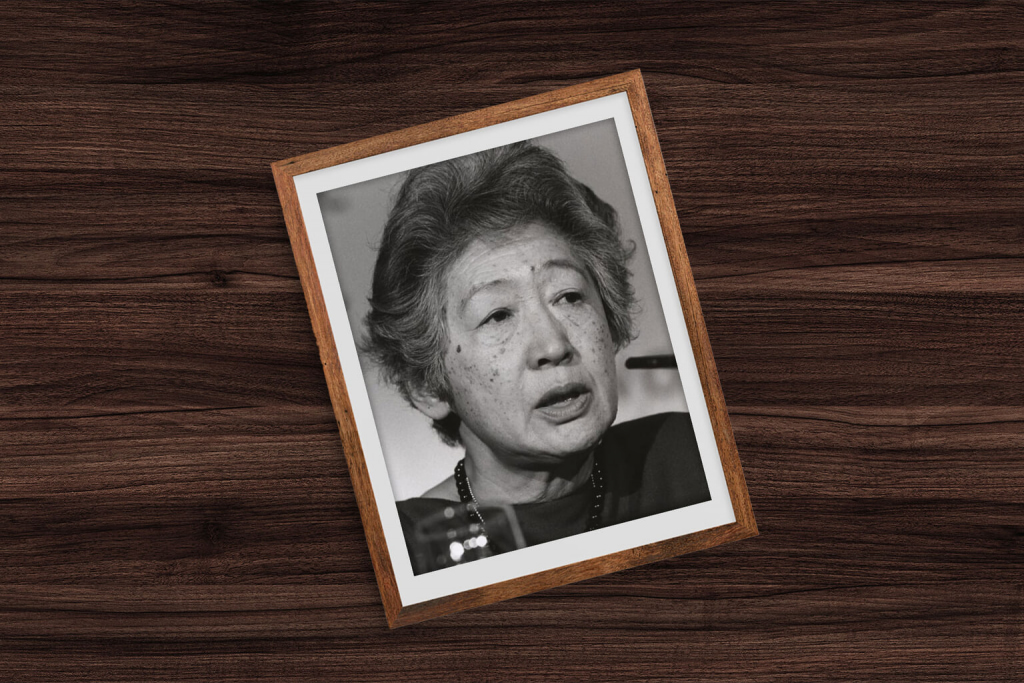

Sadako Ogata finished second in our survey asking people to name Japan’s Greatest Woman / Illustration by Rose Vittayaset

Background

Ogata, née Nakamura, was born on 16 September 1927 and hailed from a political family. Her grandfather on her mother’s side was foreign minister Kenkichi Yoshizawa while her great-grandfather was Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi. He was assassinated in the May 15 Incident of 1932 by junior naval officers. That effectively marked the end of civilian political control over government decisions until after World War II (they additionally planned to kill the visiting Charlie Chaplin, hoping that would lead to a war with the US, but fortunately he changed his schedule at the last minute).

Ogata’s father Toyoichi Nakamura was also involved in politics, working as a diplomat. Consequently, Ogata spent much of her childhood abroad including spells in America and China. Returning to Japan, she graduated from the University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo with a degree in English Literature. She then headed back to the States earning a master’s degree in International Relations at Georgetown University. That was followed by a doctorate from the University of California.

Brought up a Roman Catholic, Ogata later became a lecturer at Tokyo’s International Christian University (ICU) while raising her two children with husband Shijuro Ogata. Her first involvement with the UN came in 1968. She was invited to a General Assembly in New York by Fusae Ichikawa, a leader of the women’s suffrage movement in Japan.

Ogata subsequently spent her career switching between academe and public service. She believed her country wasn’t doing enough to support refugees around the world, expressing her views on the topic during a trip to Cambodia in 1979 following the collapse of the Khmer Rouge regime. “I think more Japanese people should do what they can for people overseas who need help,” she said.

Following the Gulf War, over a million Iraqi Kurds were displaced / Photo via Shutterstock

Changing the Rule Books

Just over a decade later, Ogata was appointed the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. She began the role in February 1991, the same month the Gulf War ended. Iraqi Kurds were fleeing for their lives following a failed revolt against Saddam Hussein.

“Almost a million went to Iran and Iran received them,” Ogata said in her book The Turbulent Decade: Confronting the Refugee Crises of the 1990s. “Then, there were some 450,000 who moved towards Turkey and didn’t quite make it across the border because Turkey had their own Kurdish minority problems. I think there was a real political problem. And a lot of these refugees, Kurds, were stuck on the mountainside.”

Flying out in a helicopter to the Iraq-Turkey border, Ogata heard directly from the refugees. Considered “internally displaced persons,” they were ineligible for UNHCR protection. Returning to Geneva, the Japanese woman pushed the commission to change its mandate to provide aid, not only for those escaping their own countries, but also those fleeing conflict within their nations. This was a watershed moment in refugee assistance.

A woman in front of Wall of names at Memorial Center Potocari, Bosnia / Photo via Shutterstock

A Ruthless Decision Maker

Not a leader to delegate from behind a desk, Ogata was regularly seen in conflict zones dressed in body armor and a helmet. She was also never afraid of making critical decisions deemed controversial by some. In 1993, she ordered the suspension of UNHCR activities in Bosnia after the Bosnian government and Serbian nationalists obstructed deliveries of food and blankets to war victims. Though heavily criticized, she stuck to her guns and five days later the Bosnian government ended its boycott.

Ogata’s next big crisis was in the Great Lakes region of Africa. Between April and July of 1994, somewhere between 500,000 and 800,000 people in Rwanda, predominantly ethnic Tutsis, were slaughtered by extreme Hutus. When the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) then overthrew the government, around two million Hutus fled the country, mostly to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

Concerned about members of armed Hutu soldiers compromising refugee camps, many humanitarian organizations halted activities in the region. Ogata, however, refused to pull the UNHCR out. Again, she was criticized. Her only concern, though, was for the welfare of civilian refugees, most of whom were women and children. From the moment she took on the High Commissioner position in 1991 to the day she finished in 2000, Ogata focused all her attention on helping displaced individuals.

“The suffering of refugees — with which my colleagues and myself deal every day throughout the world — is immense,” Ogata said in her final UNHCR address. “So is the joy of people who return to their home after years of exile. Both are much greater and deeper than words can describe. Respect your own commitment to protect the poorest of the poor, those who’ve lost their homes. Respect humanitarian workers, who are with them on the frontlines. And above all, respect refugees.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4jvQ1TQs-QU

Ogata’s Legacy

After leaving the UN, Ogata became the Japanese prime minister’s special representative on reconstruction assistance for Afghanistan. She then headed Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), an organization chartered with assisting social and economic growth in developing countries. Despite retiring as president in 2012, she continued to work with the agency in an advisory role. On October 22, 2019, the “diminutive giant” passed away at the age of 92. Her legacy, though, lives on.

“Sadako Ogata set the standard for helping refugees: principled, compassionate and effective. She was fearless in her advocacy for people, humanitarian action and political solutions,” said Secretary-General of the UN António Guterres.

Filippo Grandi, the current UN High Commissioner for Refugees, was equally effusive in his praise of the former leader. He said she’d left “a unique legacy and imprint on the UN Refugee Agency. Many millions of people enjoy better lives and opportunities thanks to her solidarity and skilful work on their behalf. And the many people today who have been forcibly displaced from their countries and homes are better served because of her achievements.”

Throughout her career, Ogata was critical of her own country’s low acceptance of refugees. “Japan has set up a situation to welcome people,” she told Reuters in 2015. “I think we should be open to bringing them in. If refugees come in millions, that’s a different story, but the arrival rate is not that huge and (to say) Japan does not have resources, that’s nonsense.”

In 2020, Japan accepted only around one percent of applicants seeking refugee status. Though the total of 47 was the highest in a decade, there seems little hope of the country changing its strict policy any time soon.