Before the big project, Sybilla Patrizia tended to take interest in moments and niches. An unassuming street sign; the dancing churn of a summer festival; a bored child on a train; an abandoned shopping cart. Likewise, much of Patrizia’s video work has comprised case studies of micro-cultures or specialized social issues.

With her latest endeavor, she has changed the tone and expanded her purview both in form and content. PLASTIC LOVE! is a feature documentary. It tackles the structures of production, consumption and management surrounding Japan’s rabidity for plastic, as the country with the second-highest plastic consumption in the world. The film is currently in production, and when I met with her this much was evident, as she brought up her hectic schedule with a demeaning laugh and maybe too much composure. Being an independent feature film creator is not only a matter of research, endless interviews, creative direction, filming and editing; but also of raising money for these activities.

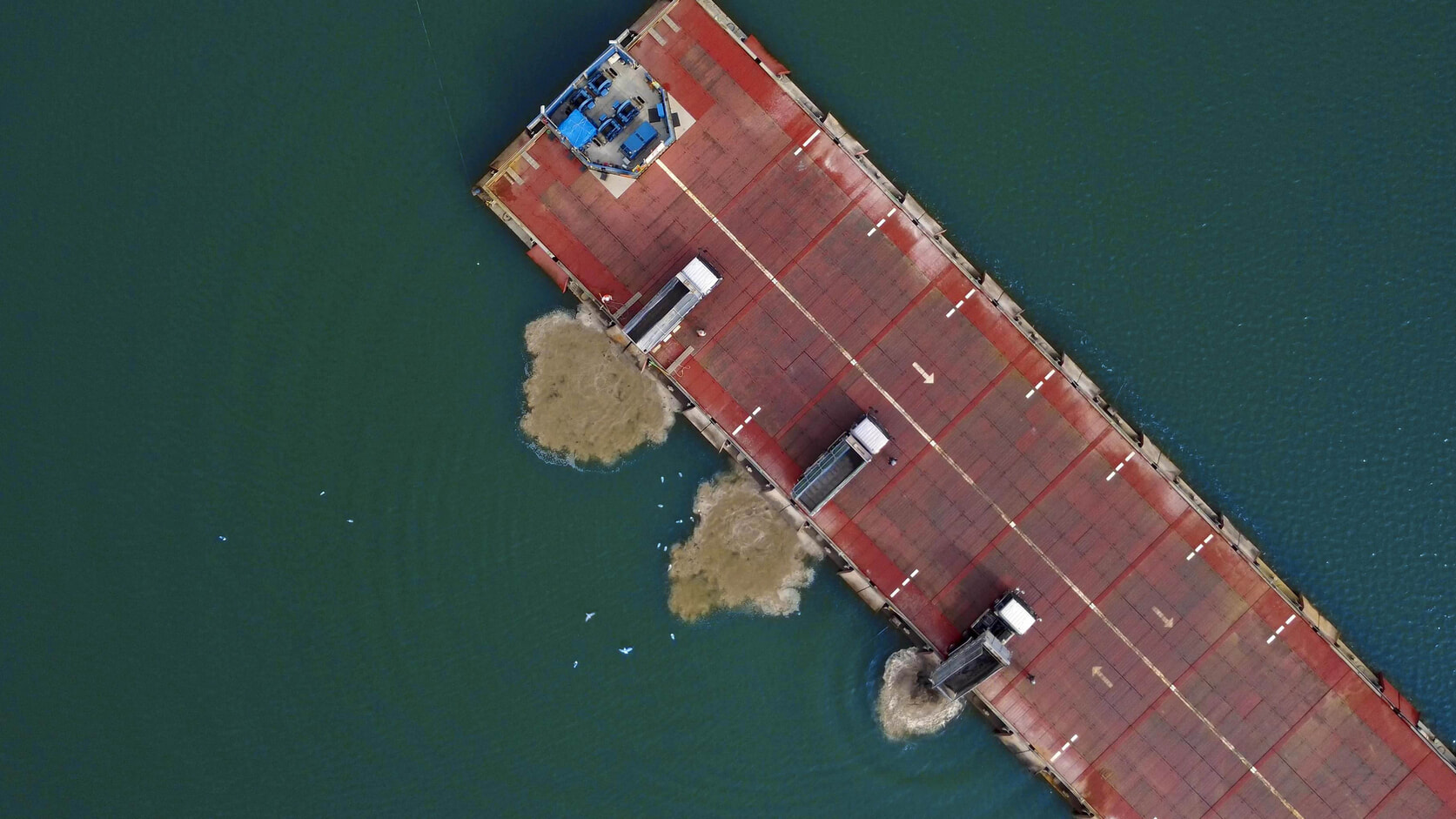

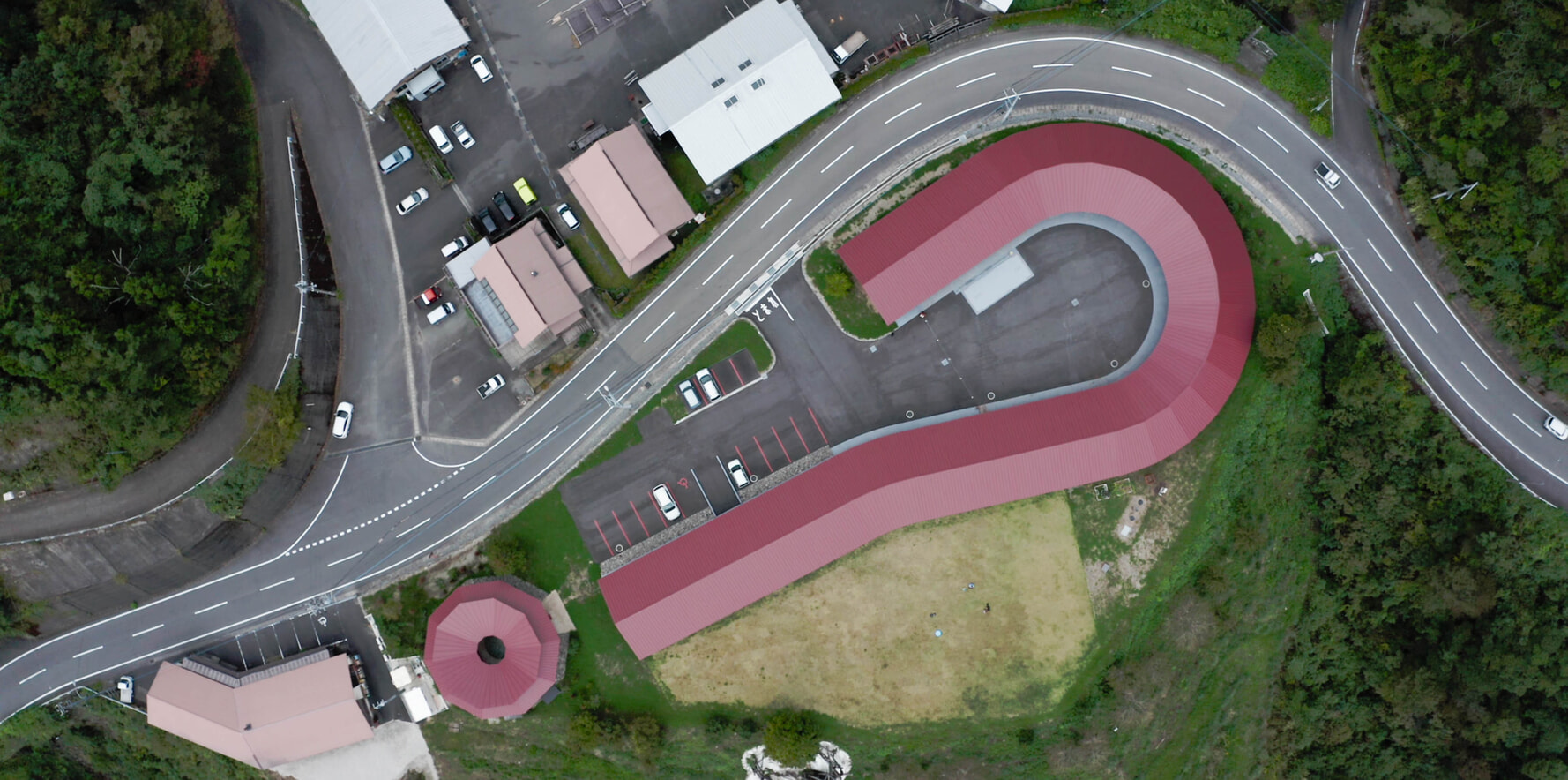

The minutiae of her street photography have given way to wide aerial shots of riverbeds, forests and highways; plastic “disposal” centers with equally monumental piles of waste; large grey pools of this waste slipping into the ocean. While the scale of PLASTIC LOVE! is enormous – the film proving to be a weighty research challenge besides a test of her endurance as an artist – it does not lack the particularity and detail that characterizes her past work. The complexity of the topic has demanded discriminating searches for her interviewees. Patrizia was thrown into an odyssey through waste treatment systems, recycling firms, municipal entities, research institutions, activist circles and more.

Patrizia has been in Japan for just about five years, but living here has been a dream of hers ever since she was a child. Growing up in Europe, she has long been fascinated by traditional Japanese culture and art, in its difference from her adolescent surroundings.

She testifies to the density of inspiring images in culture and everyday life in Japan. Her photography certainly shows an aesthetic appreciation for Japanese “street life” and public festivity, taking particular interest in, it seems, the colors and textures of people’s clothes and of the built environment. She enthused over how Tokyo in particular has so many “clashing styles” – how, for example, a lavish shopping district can suddenly lead to a quiet, residential side street.

But too often, especially in depictions of Japan and the “East,” a focus on the beautiful or fascinating appearance of a culture results in some erasure of its deeper significance, as well as the social problems that necessarily shape the culture. Patrizia, however, presents more complex portraits. She turned her eye towards such issues as period discrimination and stigmatization and the country’s involuntary sterilization of transgender people. Doing research for PLASTIC LOVE!, her image of Japan as “an amazing recycling country” gave way to the realization that recycling in the country is “almost nonexistent” (given that most of the plastic waste gets burnt, under the euphemism “thermal recycling”).

Further, she tries to make shooting a venue for interaction or experience rather than just cold documentation or staging. Whether conducting a video interview or taking photos of the street, a camera could drive irrevocable distance between the artist and subject, and could be seen as an instrument of intervention. But one of Patrizia’s provisions seems to be the comfort and ease of her subjects, and the degree of naturalism that comfort provides.

I asked her about her shoot-from-the-hip photography, particularly her matsuri series. I wondered, were these pictures, especially the blurry shots, as impromptu as they looked? Or was the street photography as staged as the fashion shoots? While as of late, making the movie has required her shooting gear to only get bulkier, Patrizia would have bristled at bringing big cameras to the summer festival. She attended the matsuri first; taking pictures was secondary. She had only a tiny, inconspicuous film camera with a flash.

“So you can go up to people and shoot and get into the middle of where everything’s happening. Whereas sometimes, if you show up with a big camera and big gear and you draw so much attention to yourself, people become really self-conscious of their behavior. When I go to those matsuri to photograph people, I feel like I’m almost invisible because I’m just shooting with this little box,” she explains.

“What it does, though – it allows me to get super close to people. For that project [matsuri] it’s all about being right in the middle of that moment while people are screaming and dancing, and it’s hot and humid – I can almost hear the music while I’m looking at the picture, and it’s just so raw. You also don’t know how the pictures come out because I’m shooting with film… I just love the rawness of it.”

In general, she likes to at least have a conversation with a subject – of a photo, a video – before shooting them. A grin grows on her face as she recalls two charismatic garbage truck drivers she interviewed for PLASTIC LOVE!. They promised each other to hang out sometime.

While she is mediating the voices surrounding the plastic issue, she ultimately sees herself as an artist, responsible over representation rather than disputation. Perhaps this belief is what accounts for the particular warmth, ease and idiosyncrasy of her photos; she approaches the essence of her topic without cold artistic remove or being overwhelmingly didactic.

“I guess I would say that I’m a documentary filmmaker and photographer, but at the same time I also think of it in the way of – what can I bring to the table that other people can’t, as a journalist or an activist? And that’s the art part… There are certain topics that are really important for me, but I’m trying to convey them in a specific style that grabs your attention and gets people to be interested in that topic. That’s the one thing that I can do as an artist, is bring my creative vision to the table.”

PLASTIC LOVE! – Unwrapping Japan’s toxic love affair with plastic is expected for release in early 2022. For more details about the film, visit the film’s official website.

You can check out more of Patrizia’s work over on her website.

This article was published in the Sep-Oct 2021 issue of Tokyo Weekender. To flip through the issue, click the image below.