Spotlight is a news series profiling influential Japanese people in the 20th century. We begin with Chiune Sugihara, the man known as the “Schindler of Japan.” In 2016, he was voted number one in a TW poll asking Tokyo residents to name this country’s greatest ever person.

Background

Sugihara was born in the rural town of Mino in Gifu Prefecture on the first day of the 20th century. He spent his early years living with his family in a borrowed temple. As a youngster he dreamed about a career as an English teacher, but his father had designs on him becoming a physician. In an act of defiance, the teenage Sugihara deliberately flunked the entrance exam, writing only his name on the paper. He instead went on to major in English literature at Waseda University. It was an early indication of his rebellious streak.

He was not a man to simply go with the flow if he felt something wasn’t justified. After passing an exam for the Foreign Ministry in 1919, he was sent to Harbin in China to study Russian. He then served in Korea for a year, before returning to northeastern China where he was recruited by the Japanese Consulate. Harbin fell under Japanese control in 1931 and became part of the puppet state of Manchukuo a year later. In protest at his country’s mistreatment of the local population, he quit his post as deputy foreign minister in 1935.

An expert in Russian affairs as well as being fluent in the language, Sugihara was assigned to serve in the Soviet Union in 1937 but was refused entry. He was posted in Finland instead, working in the Information Department of the Foreign Ministry. Two years later Japan opened a new Consulate in the Lithuanian city of Kaunas. It was seen as an ideal place to keep an eye on its ally Nazi Germany. The fear was that Adolf Hitler was secretly negotiating a pact with Joseph Stalin. Sugihara was appointed as vice-consul.

Visas For Life

On August 23, 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact. It effectively divided up Eastern Europe for conquest by the two nations. The following month, both countries invaded Poland. At the time Lithuania was a haven for Polish Jews looking for an escape route. The situation changed after it was occupied by the USSR on June 15, 1940. Though they didn’t face systematic murder, many were persecuted as Communist ideology was against all religions. Thousands were sent to Siberian labor camps. The anti-capitalist campaign also meant several Jewish merchants lost their businesses.

The fact that Nazi Germany was rapidly advancing east was even more concerning for Polish and Lithuanian Jews. Their only hope of survival was to obtain a transit visa. Jan Zwartendijk, acting consul from the Netherlands, had issued final-destination permits for the Dutch colonial territory of Curaçao, where visas weren’t required. They still needed transit visas, though. That’s where Sugihara came in. Whereas other diplomats in Lithuania had to close office in August, he managed to negotiate with the USSR to stay open until September. The last man standing, he wired three requests to the Japanese foreign ministry for approval of the visas. Three times he was refused.

He was told not to issue them to anyone who hadn’t gone through the appropriate immigration procedures or didn’t have enough funds – pretty much everyone who lined up outside the consulate building. Taking matters into his own hands, he issued 10-day visas for transit through Japan. He reportedly worked 18-20 hours a day, stamping more than 2,000 visas. On top of that, he used his Russian skills to negotiate with Moscow officials to ensure refugees could pass through the Soviet Union and would be able to leave Vladivostok for Japan. Stalin agreed to the transit orders.

A Savior to Thousands

As most of those involved included dependents, it’s estimated that somewhere between 6,000 and 10,000 people were able to escape thanks to the selflessness of Sugihara and Zwartendijk, though the official number will never be known. Two people they did rescue were Nissel Wajsbrod (known in America as Nathan Waisbrot) and Moczek “Moshe” Goldszmid. Five days after Germany invaded Poland, the pair left their hometown of Polaniec. They spent 10 days traveling by bicycle to the Soviet border where they ran into a Polish police officer. Putting their bikes on a supply wagon, he was able to get them across state lines. Making their way to the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius, they got in contact with Rabbi Zerach Warhaftig. He was an influential lawyer who spoke to Sugihara about issuing visas for refugees.

“Warhaftig was able to connect my father and Moshe to Sugihara,” says Wajsbrod’s daughter Faye Honor. “They were numbers 1473 and 1477. After getting the visas, they had 10 days to leave the Soviet Union or risk being shipped off to Siberia or jail. My dad went on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok before getting on the boat to Japan. He spent much of 1941 in Kobe working for a refugee organization. He then headed to Bombay in 1942 followed by Palestine. His uncle sponsored him to go to the States where he was later joined by Moshe. Unfortunately, he passed away in 1960, but I eventually heard his story from Moshe who lived until he was 96. Most of their families were murdered during the war but they were able to get out thanks to those visas from Sugihara. His compassion for the fate of the Jews saved many.”

Sugihara’s Legacy

Sugihara went on to serve in East Prussia, Czechoslovakia and Romania. When Soviet troops entered Bucharest in 1944, he and his family were forced to spend 18 months in a prisoner-of-war camp. Released in 1946, they returned to Japan the following year. Sugihara was then asked to resign by the foreign office. The official line was downsizing, though many, including his wife Yukiko, believe it was because of what happened in Lithuania.

For decades, little was known about Sugihara. Things changed in the years leading up to his death. In 1985, a year before his passing, he was recognized in Israel as Righteous Among the Nations, a title given to non-Jews who showed great courage during the Holocaust. Interest in the former diplomat has continued to grow since. He’s had streets, museums and an asteroid named in his honor. Numerous books, documentaries and films have been written about him, including the 2015 movie Persona Non Grata.

“My father did what he felt was right even if there were repercussions,” Sugihara’s only surviving son Nobuki Sugihara told us in 2016. “He never thought of himself as a hero and rarely talked about what he did in Kaunas. I knew nothing about it until I was 19. He got a call from the Israeli embassy in Japan and we went there together. Commercial attaché Jehoshua Nishri, whose family had been saved by a visa [my father] issued, managed to track him down after trying unsuccessfully through the ministry of foreign affairs numerous times. Nishri informed us that many others had escaped. My father never really displayed his emotions, but that was pleasing for him to hear because he had no idea what had happened to them.”

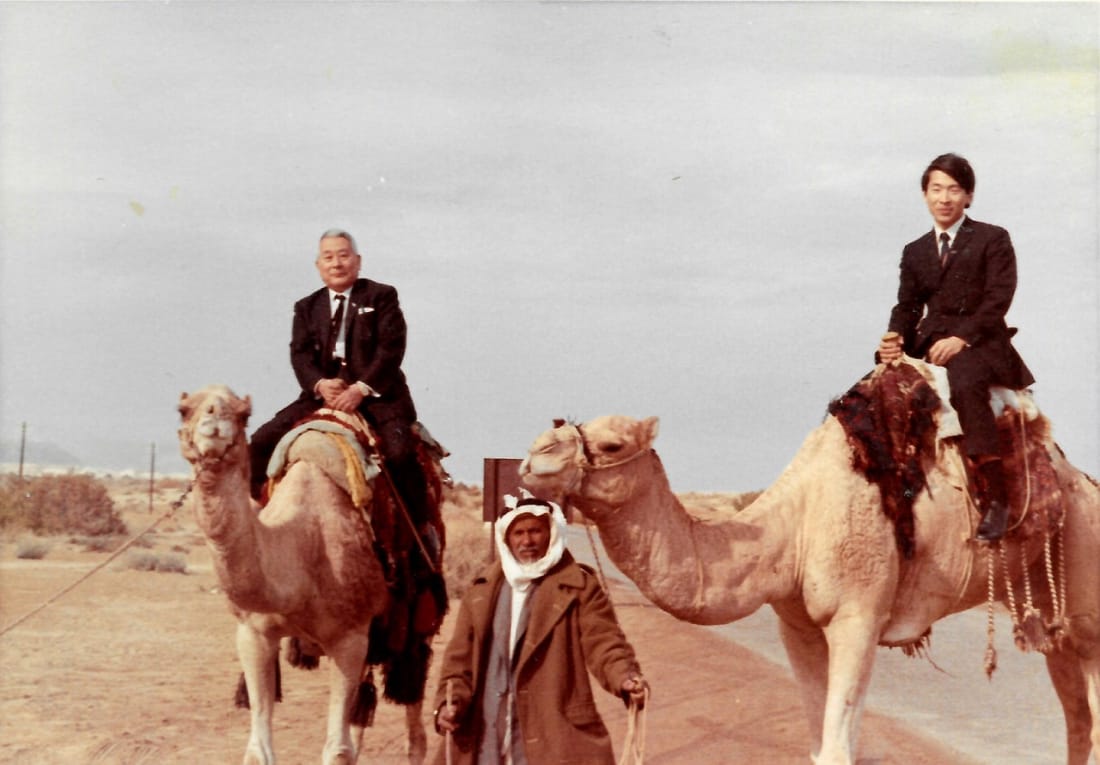

Images courtesy of Nobuki Sugihara

Updated On June 14, 2021