Searching for the essence of an ancient Japanese city based on a turn-of-the-20th-century metaphorical love letter could accurately be described as a quixotic quest. Nonetheless, last autumn, I found myself in Matsue, Lafcadio Hearn’s “Chief City of the Province of the Gods,” with just that idea in mind.

Granted, it’s not unusual to find a writer with inextricable links to a geographical place: Hemmingway’s Madrid, Kafka’s Prague, Lawrence’s Sicily, Joyce’s Dublin. But what about a 19th-century wayfaring journalist of Greek-Irish heritage becoming the anointed son of an old samurai stronghold in western Japan?

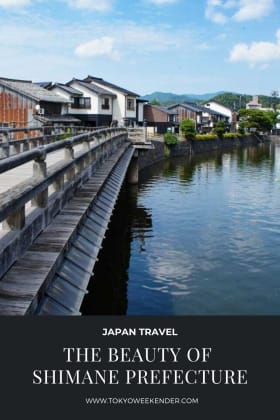

Matsue Station, Shimane Prefecture

Lafcadio Hearn’s Matsue

In Matsue, a small castle city whose jagged coastline greets the Sea of Japan, Lafcadio Hearn did exactly that. Born in 1850 to an Irish father and Greek mother on Lefkada in the Ionian Sea, Hearn’s upbringing was marred by familial abandonment and financial strife. But it was the scars of his childhood, and an to introduction Japanese folktales in later life, which fuelled the body of work for which he is most renowned: kaidan, or ghost stories.

Though Hearn arrived in Japan aged 40, an established and culturally curious journalist, it’s strange he ascended so quickly to the upper echelons of Japanese literary immortality. For a start, he could barely speak a wink of Japanese, and could read even less; something he was never short of rationalizing.

The entrance to the former residence of writer Lafcadio Hearn in Matsue, Shimane

“It is safe to say that no Occidental can undertake to render at sight any [Japanese] literary text laid before him,” he wrote with some confidence in an essay not long before his death. To circumvent the painstaking task of learning Japanese, Hearn even developed a kind of baby-talk dialect to communicate with his wife, the daughter of a déclassé Matsue-based samurai family.

Furthermore, though he was widely praised for having an aesthete’s eye, Hearn was essentially blind. He lost sight in one eye in a playground accident (which is why all remaining photos of him are side profile) and the other was so short-sighted that when he walked into a room, he’d often grope surfaces and objects to acquire his bearings.

This never got in the way of his descriptive prose, which came out in full fervor where Matsue (his first adopted hometown in Japan) was involved. “But oh, the charm of the vision, — those first ghostly love-colors of a morning steeped in mist soft as sleep itself resolved into a visible exhalation,” Hearn wrote of a typical Matsue morning.

Chasing Lafcadio Hearn

Naturally, the artist informs the art. And when you have a body of work as wide ranging as Hearns, from Creole cuisine cookbooks and West Indies’ travelogues to ghost stories and philosophical essays on Japanese people and aesthetics, you have quite an enigmatic character to deal with.

So, when myself and my girlfriend rolled our Tetris Block rental car onto the tree-lined streets of Matsue, it was this enigma behind the art I was chasing, along with the remnants of the city which so endeared him.

“The first of the noises of a Matsue day comes to the sleeper like the throbbing of a slow, enormous pulse exactly under his ear. It is a great, soft, dull buffet of sound — like a heartbeat in its regularity, in its muffled depth.” Such are the opening lines of Hearn’s ‘The Chief City of the Province of the Gods’ essay, referencing komestuki (rice cleaners) at work in the early hours of the morning.

Matsue

Today, this same passage more accurately describes the distant drone of cars swarming into the city on their daily commute. Like most Japanese cities, Matsue is no longer a town of geta sandals clip-clopping on flagstones and of coolies whipping round the pedestrian streets pulling hand-drawn carts.

Multi-lane highways are a dominant force on the drawing boards of 21st-century Japanese city planners, and as Shimane’s prefectural capital, Matsue has not evaded the forces of civil construction. Nor is urban change a recent development — in the late 1800s, Hearn was already lamenting the first signs of modernity in provincial Japan.

Though visual monotony is often the trade-off we make for convenience, Matsue has not lost all of its charm. The city loops around the bay of Lake Shinji, which sparkled in the late afternoon sunshine as we rolled Tetris Block along its flanks.

It was on days like this, I imagined, where the water’s rhythmic and sun-splashed surface caused Hearn to liken it to the Ionian Sea of his early childhood. Magnifying Lake Shinji’s grandeur is a lone islet, Yomegashima, believed to have appeared many years ago out of the blue (quite literally), and topped with slender red pines resembling acacia trees in the African savanna.

Matsue Castle

The Man Behind the Art

This dramatic setting leads toward the eponymous Matsue Castle, which sits in black tiers brooding over the low-rise skyline. Its in this area, Matsue’s most fetching, where the old samurai residences remain, one of which was Hearn’s former home.

How Hearn ended up in such a peachy abode within a year of moving to Japan is simple: a marriage of convenience. Marrying into local families was a common ploy for gaijin assimilating to life in Japan in the post-Meiji Restoration era. The arrangement was also a potential stepping stone en route to Hearn’s ultimate journalistic goal: “thinking with their thoughts.”

He later realized, however, thinking like a Japanese was an inherently impossible task. “One would need to be born again, and to have one’s mind completely reconstructed,” he noted in the seminal essay, ‘Strangeness and Charm.’ At least the marriage went the distance.

We stopped Tetris Block nearby Matsue’s samurai quarter, and made our way along the castle moat sitting opposite the residences. Squat-trunked black pines hung drunkenly over the bottle-green water, where small, wooden cruise boats drifted past the castle’s cyclopean foundations.

We headed to the museum by Hearn’s former residence at the street’s end, where a collection of idiosyncratic trinkets displayed in cabinets illuminated his character in a new light: a monocle for his good eye; an office space with floor cushions, writing pens, a tobacco humidor and smoking pipe; sepia-stained notebooks, travel sketches and letters penned to his wife in their bizarre private language.

A trumpet shell sat in one corner, which Hearn used to blow as shorthand for “bring me my pipe dear,” while some letter excerpts showed how he doubled-down on the whisky when his heart started failing him. These snapshots of the eccentric, emotional, and often irascible, man behind the words, tell their own tale. Hearn is most remembered for stories involving supernaturality and death – he was arguably consumed by them – but that never stopped him from living life.

Sunset in Lake-Shinji, Matsue, Shimane

The Sun Always Sets on Matsue

In a last gasp attempt to see the city through Hearn’s eye, we made for the sunset on the shores of Lake Shinji. We sat as the sun dipped toward the horizon, which hides behind a thin strip of land to the west, admiring the surrounding “demilunes” and the “silhouette of the pine shadowed island” as Hearn did almost 130 years prior.

The sun streaked the sky in crimson, in waves of pink and whisps of mauve, until a bubbling black cloud stampeded across its path gobbling up the last of the day’s rays. A potent, if slightly disquieting, analogy for the beasts of modernity gobbling up this city – nearly all Japanese cities.

But while the Matsue Lafcadio Hearn adored is largely confined to the halls of antiquity, the legacy of Hearn the man endures is as strong as ever. All you need to do is look.

For more information on Lafcadio Hearn and his life and work in Matsue, see the official website of the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum in Matsue here.

Updated On April 19, 2021