Who needs calendars to tell what time of the year it is when you can use food instead? Plenty of countries use seasonal dishes to help mark the passing of time. In the west, for example, autumn is almost synonymous with pumpkin spice drinks, and while it’s not impossible to find the same here in Japan, the country offers something better to signal the beginning of the cold autumn days: oden.

Although often perceived as more of a winter dish, oden tends to appear almost as soon as temperatures drop, and since Japan’s climate doesn’t really believe in gradual cooling, October has long been the unofficial start of the oden season. But what is it exactly?

Oden is a hot pot dish where various ingredients are all simmered together in a single container. But not in water. The basis of oden is a soy sauce-seasoned dashi broth (Japanese stock of kelp and preserved bonito flakes, although hundreds of different variations exist out there). Dashi is what gives all sorts of Japanese dishes — from miso soup to tamagoyaki rolled omelets — their distinctive hit of umami/savoriness, and even with the lighter broth that you’ll find in oden, boiling things in dashi always enriches them with complex, deep flavors.

You can get oden at some restaurants but for an authentic Japanese experience, you have to get it from a cart or a convenience store, which sells oden by the ingredient, serving them in a bowl of dashi. Here are your best options.

Daikon (大根)

The sturdy Japanese radish becomes like a sponge for dashi after it’s been simmered in it long enough. Oden daikon usually comes in the form of small pucks.

Konnyaku (こんにゃく)

One of the most popular oden ingredients. It’s a kind of gelatin made from the starch of an Asian yam. Without additional seasoning, it’s a somewhat bland dish but it acquires subtle flavors and a pleasant, firm texture after an oden bath (where it appears cut into grayish triangle shapes.)

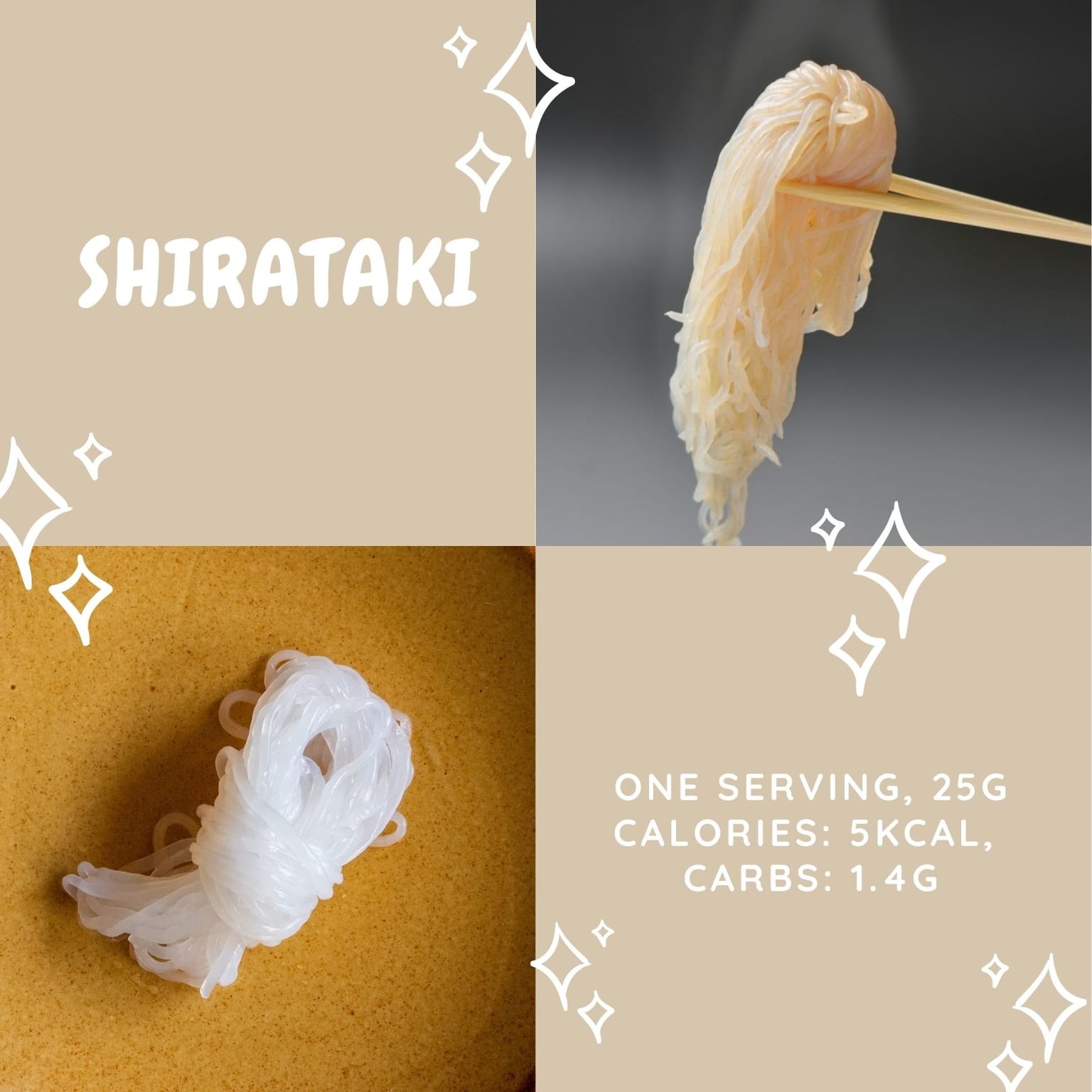

Konnyaku has virtually no calories and is extremely rich in fiber, so it’s recommended for stomach problems. A delicate noodle-shaped konnyaku, which also appears in oden, is called shirataki (白滝/しらたき).

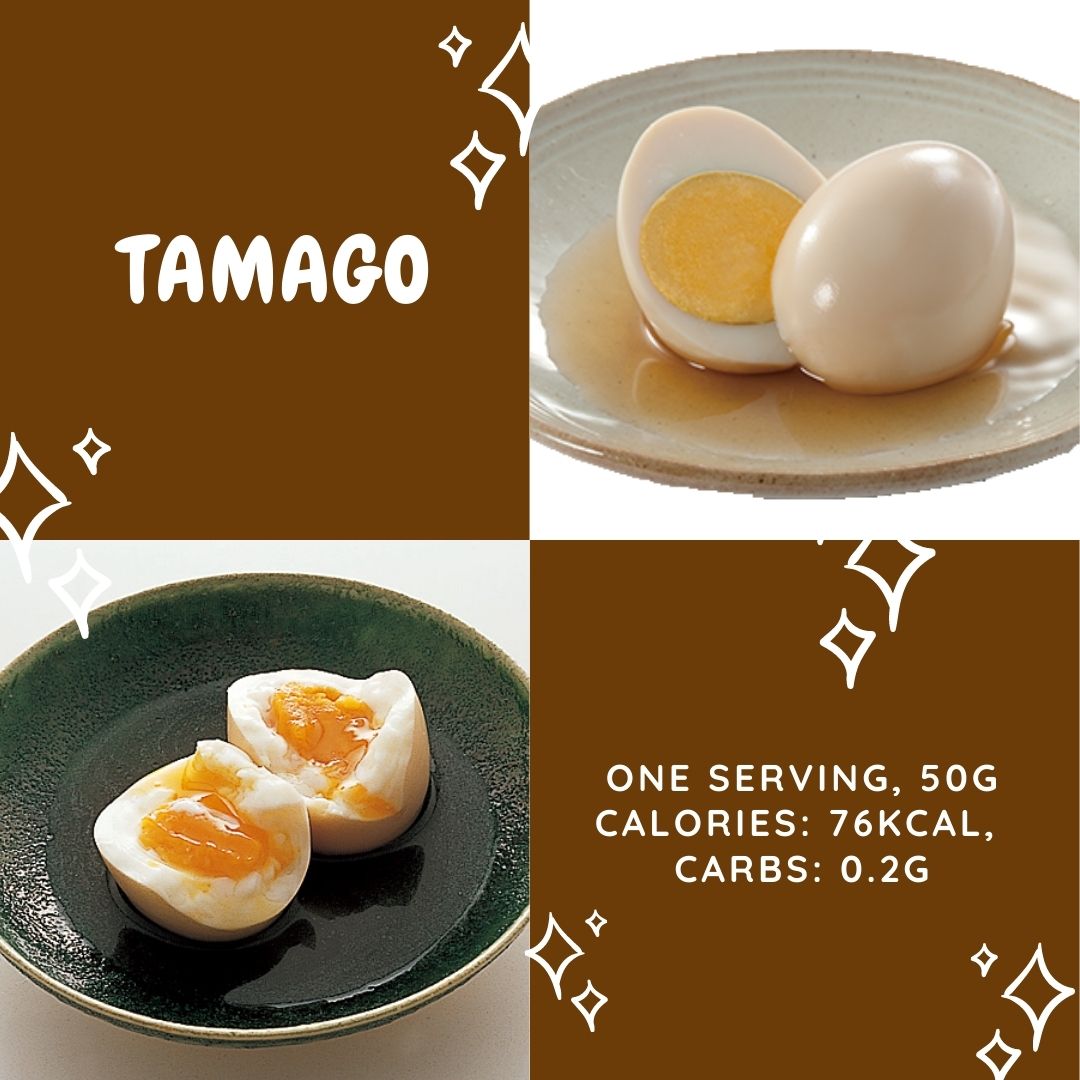

Tamago (卵)

Boiled eggs. A classic oden ingredient that, thanks to dashi’s bonito hints, tastes a little bit like a warm pickled egg, but in a good way.

Fishcakes

If oden had something like a main ingredient, it would be fishcake in all shapes and sizes. For example, there is chikuwa (ちくわ/竹輪), a starchy fishcake in the shape of a cut bamboo stalk.

There is also hanpen (はんぺん), which is a white triangle-cut pollock fishcake that’s melt-in-your-mouth soft.

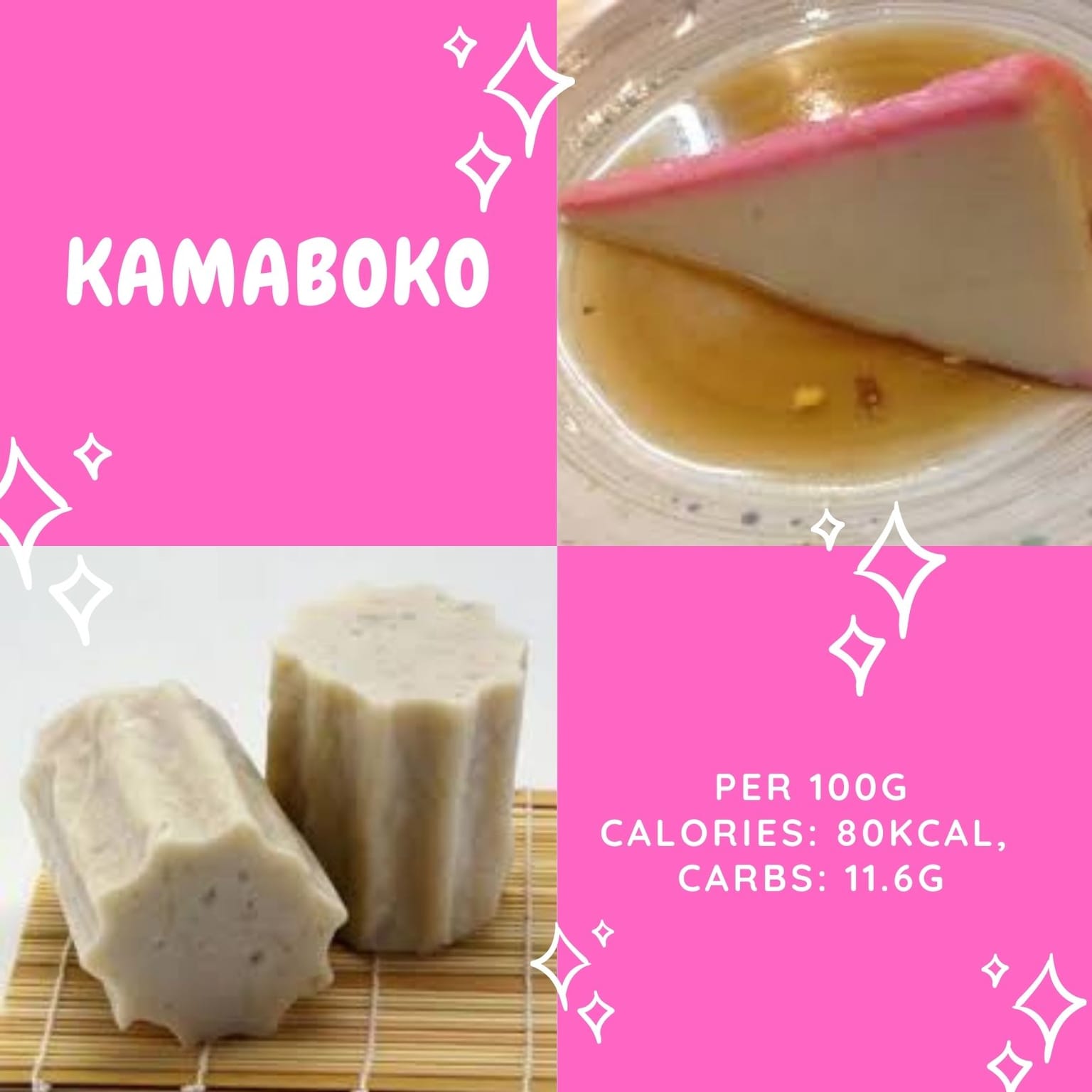

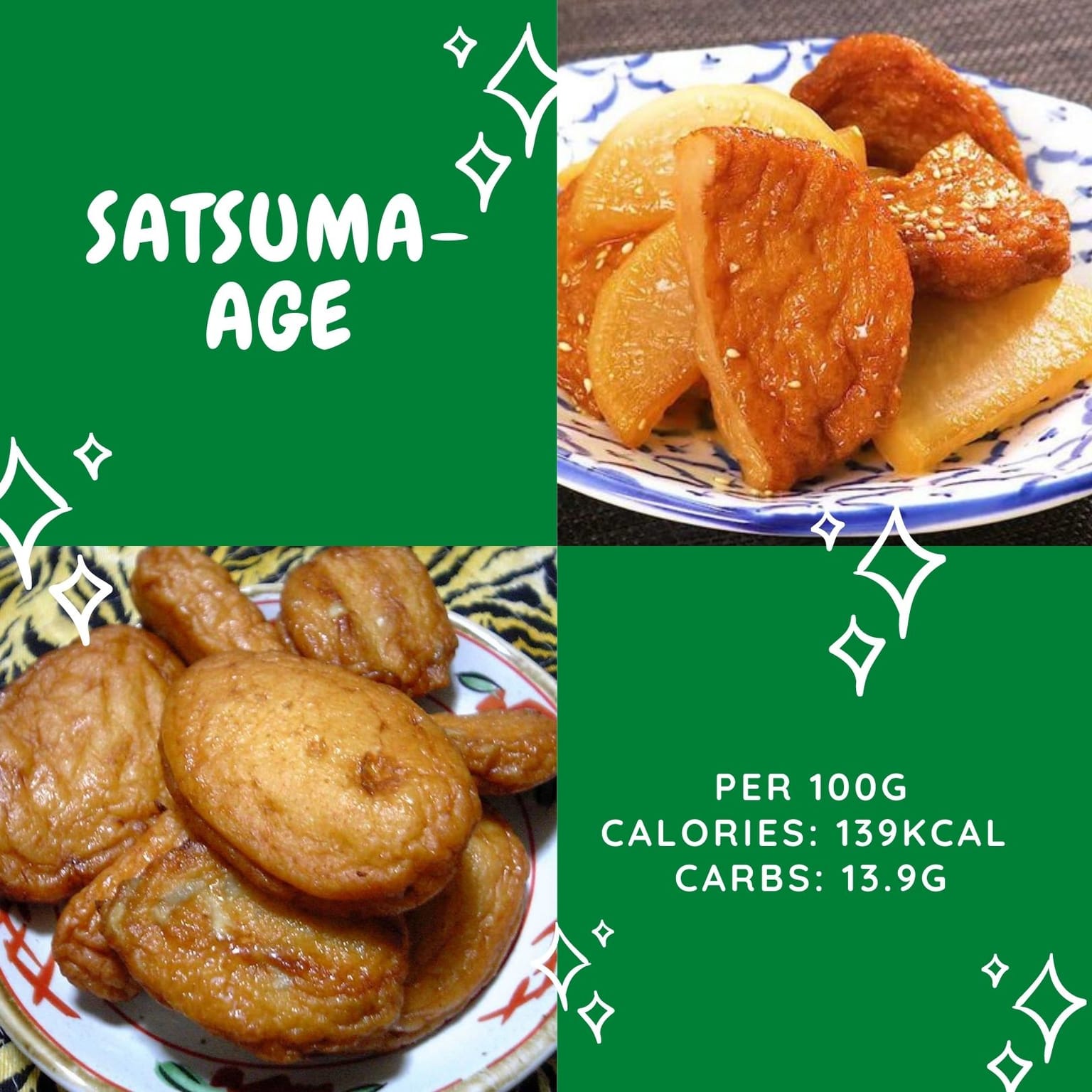

Kamaboko (かまぼこ), a delicate white-and-pink fishcake, is another popular oden ingredient, as is the fried satsuma-age (さつま揚げ) fishcake and tsumire (つみれ), a fish-paste meatball.

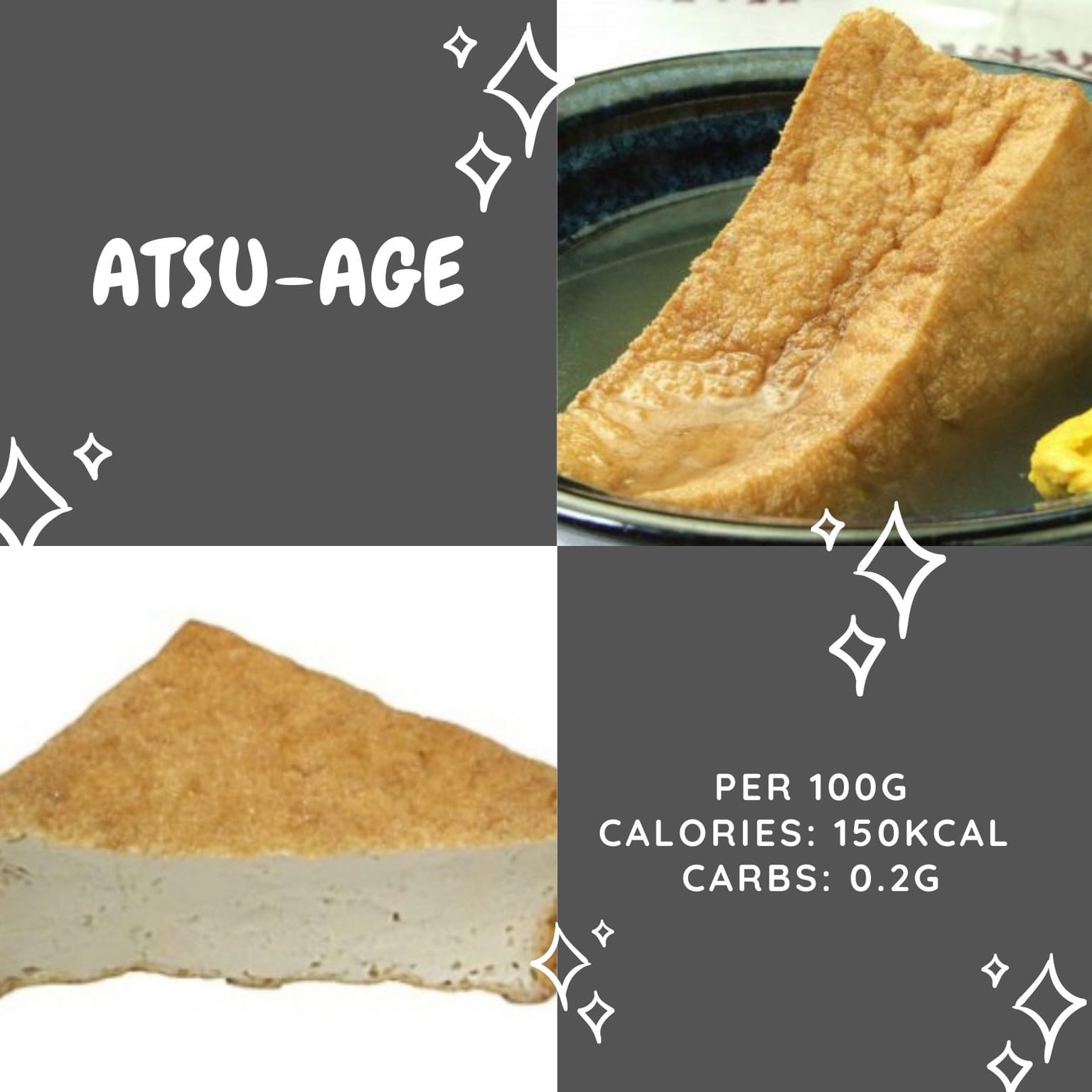

Fried Tofu

Another oden ingredient that likes variety. Oden fried tofu can come in the shape of atsu-age (厚揚げ), which is a thick, deep-fried block of tofu, most often cut into edible chunks, or ganmodoki (がんもどき, 雁擬き), a fried tofu and vegetable fritter, often shortened to just ganmo.

Then, there is one of the most singular oden ingredients ever: kinchaku (巾着). Literally meaning “pouch,” it’s fried tofu in the shape of a pouch with mochi rice inside.

It’s delicious but be careful because after boiling, the mochi inside tends to become lava-hot.

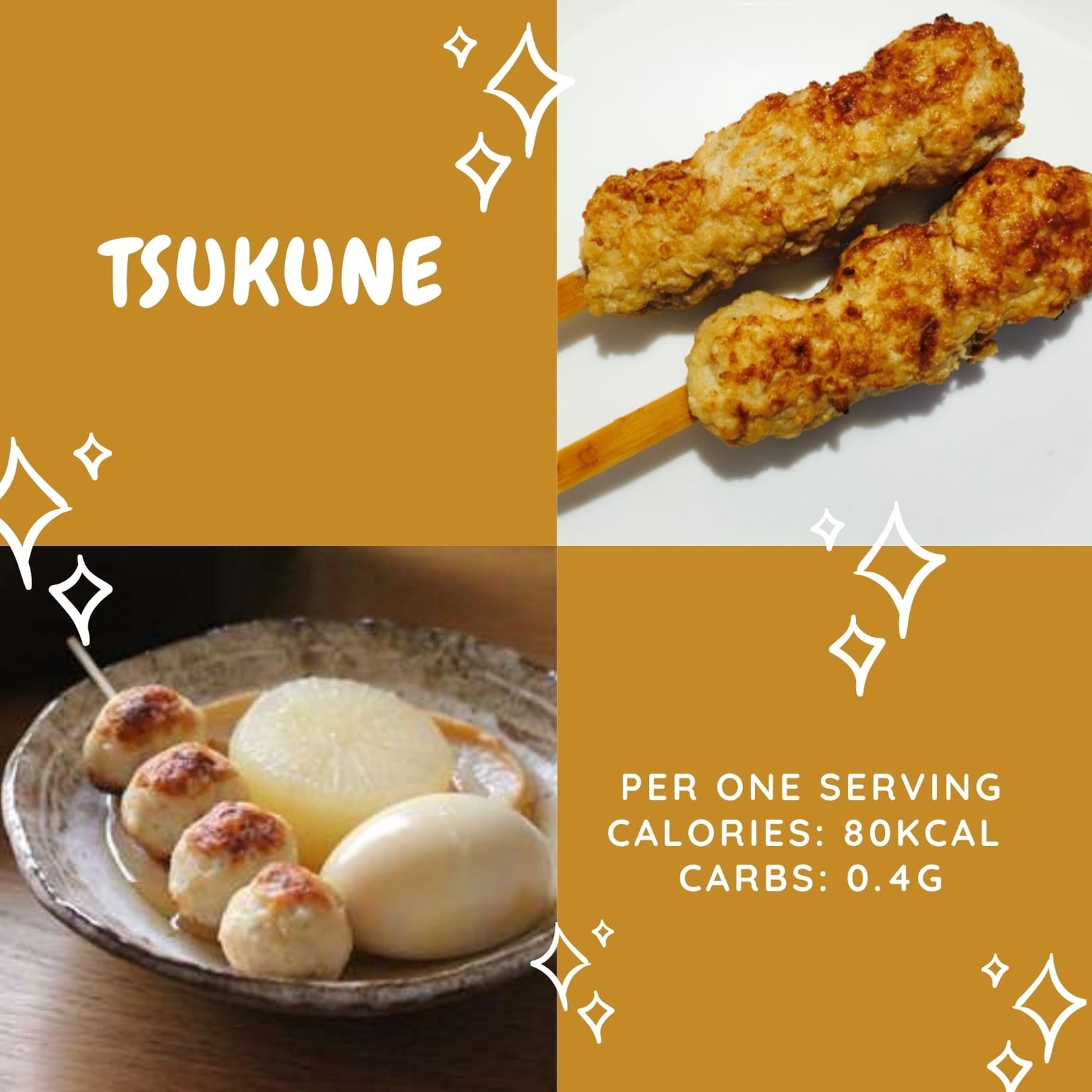

Meat

Carnivores rejoice because oden has something for you as well. Gyusuji (牛筋) beef tendons/sinew that become unbelievably soft and fatty after being simmered in dashi are an oden favorite.

You can also get wieners (ウィンナー), tsukune (つくね), chicken meatballs, or roru kyabetsu (ロールキャベツ): rolled cabbages stuffed with pork or beef.

Whatever you go with, don’t forget to smear a little bit of Japanese karashi mustard, miso sauce, or yuzu pepper paste on the side of the bowl, so you can dip your ingredients in them and give them a little extra kick.

Now that you know all about oden — go buy some from your local convenience store! You’ll be glad you did!