Ten years. According to every Japanese artisan I have interviewed over the last seven years, this is the length of time it takes to master one’s craft. I have heard this response so often that at times, I’ll admit, I even wondered: is it truly necessary to spend a decade learning how to fashion a bamboo whisk or prepare green tea? Surely a one- or two-year apprenticeship would suffice? But we forget, you see, that becoming a shokunin (craftsman) in Japan is about far more than just learning a skill. It is a way of being. A constant, driving purpose. It’s all tied up in the concept of ikigai, which can loosely be understood as one’s “reason for getting up in the morning.”

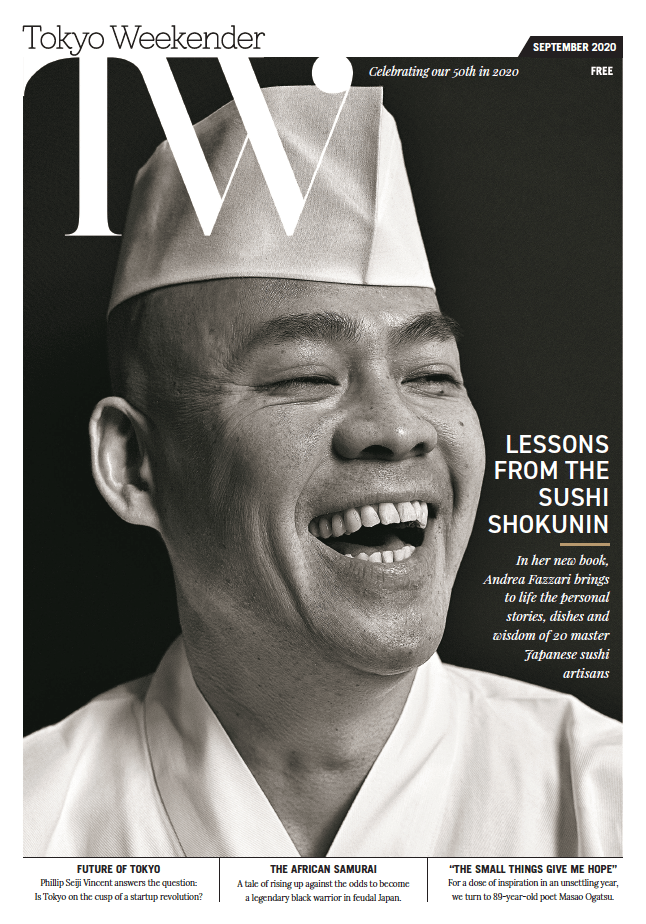

In the introduction to her new book, Sushi Shokunin, award-winning photographer and author Andrea Fazzari reminds us of the deeper significance in being a shokunin: “Concurrently, they are altruistic leaders, teachers, and artists of tremendous spirit and skill, who strive for excellence not only for themselves, but also for the benefit of others … This dedication to a lifelong pursuit of the highest level of mastery … affords all types of shokunin a respected and integral role in Japanese society.” When I consider this — and, indeed, when I read the stories and words of the 20 sushi chefs Fazzari interviewed — I find myself sheepishly thinking: how could I have questioned 10 years as an exaggeration? To reach the level these craftsmen strive for is the work of a lifetime.

Guests dining at Sushi Sho in Honolulu. ©Andrea Fazzari

As you run your hands over the pages of Fazzari’s beautiful silk-covered tome (which she co-designed), you’ll marvel at her crisp photography, the way she can make a grain of rice look like a tiny crystal, the way she can tease out an enormous amount of expression from an otherwise solemn Japanese sushi chef. But most of all, you will feel all the reverence of the shokunin you will come to know.

“It’s not just a job. It’s way of thinking and behaving.”

Because you really do get to know them. As in her first book, Tokyo New Wave, which focused on younger, more modern chefs in Japan, Fazzari reaches deep into each subject’s personal life, taking you all over the country to their childhoods, through their challenges, and into their restaurants. Here, seated at their sushi counters, she describes their artful cuisine in such vivid detail you’ll feel as though you’re eating it along with her. And when she is moved to tears by one dining experience, you may find yourself welling up too.

As much as the chefs she focuses on are shokunin, I’d like to say Fazzari is her own kind of shokunin. It’s rare to find a master storyteller like her.

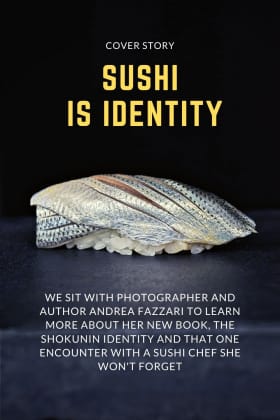

Lean tuna marinated in soy sauce (akami zuke) at Mitani. ©Andrea Fazzari

The chefs talk about sushi as though it’s life and death. You yourself were moved to tears during one meal. How can sushi be so powerful?

A few of the chefs said to me, as I quoted from Hidefumi Namba, “If you take sushi away from me, I have nothing.” Sushi is their entire being. That was echoed often. Also, the history of sushi as an Edo cuisine defines Japan — there’s a lot of nostalgia around Edomae cuisine, because it’s so symbolic and emblematic of the country. In addition, these chefs have so many memories of growing up and having special occasions when they would always have sushi, usually delivered to their home. It was a visceral experience for many of them when they ate at a sushi counter for the first time. It’s also that sense of duty and belonging; that sense of learning something so well in the Japanese tradition; that notion of doing the best you can and having that ikigai. These men really feel this purpose with a great sense of gravity. Finally, they are also often thinking of their predecessors: are they doing them proud? They want to carry that torch with pride and dignity.

Tell me more about your moving meal with chef Takaaki Sugita.

That dining experience was very important to me as it was the first time I got back to sushi after my illness [a tropical disease that left Fazzari unable to eat sushi for years]. Sugita-san is really important to me and I dedicated the book partly to him. What touched me so much was how he talks about propriety, of sushi being pure and brave, and of belonging to a way of thinking. The shokunin believed that, without sushi, their days would feel empty. Shokunin work every day on the same thing, with tons of repetition. This dedication I equate to a spiritual place. It’s not just a job. It’s way of thinking and behaving.

“There are a lot of chefs who strive for excellence, but shokunin are different – they are artisans”

Sugita-san is extremely emblematic of this. I was so touched by that meal because it was like watching a performance, like an opera or something. It was incredibly moving and made me emotional … the ceramics, the flavors, the senses, the aromas, sitting in front of him, how he handles everything, how he closes his eyes, it’s so special and otherworldly. I admire people who are so dedicated to their craft.

Many of the chefs talk about needing perseverance to get through those long, badly paid apprenticeships. Do you think that’s what gives them the standout factor?

They have an inkling when they’re young; they’ve heard stories about grueling apprenticeships. It takes a lot of dedication and strength of spirit to get through them. But it’s more worth it, in the end, having gone through such a hard journey. They build fortitude and strength. This is, in part, how the shokunin mind gets formed. Those who do see it through find a rhythm and that sense of belonging. They become goal-oriented and choose a life of pursuing mastery — again, that reason for getting up in the morning. To give that up would feel like failure. There are a lot of chefs who strive for excellence, but shokunin are different. They are artisans. They have a sense of working with nature, being mindful of their predecessors, and inherently approach food differently than chefs. Sushi is not a cuisine, many of them told me. It’s sushi. It’s emblematic of the country. It’s fish, rice, soy sauce, wasabi. It’s the Japanese aesthetic. Sushi is identity.

Keiji Nakazawa catching opah. ©Andrea Fazzari

Sushi is known as fast food in Japan yet the meals you enjoyed were three hours long.

Sushi did start out as a fast food, sold at food stalls; a merchant cuisine in the city with quick turnover. It has evolved over time into something that is more of a statement, more about enjoying the otsumami and nigiri at a slower pace, a dining experience rather than a quick bite. Some artisans are still speedy: for example, Jiro-san’s dining experience lasts 30 minutes. But this is too fast for me. I prefer a longer meal where I linger and can savor.

Gizzard shad (kohada) at Chikamatsu. ©Andrea Fazzari

Is sushi now your favorite Japanese food?

I’ve had a long relationship with sushi. Now it’s stunning to me because it’s so of the country, and I understand it and love it for all it represents. It is artful. Some of the shokunin may not think of themselves as artists. There’s a difference between artist and artisan. But I feel they are both. The dining experience really transports me to another world, another way of being and a better understanding of this life in Japan.

“Perfection is never reached, but striving for it is what is important.”

Can an average customer get this same experience?

Some can; it depends on what you bring to the experience. I know a few people who find it powerful to eat at these sushiya. It’s maybe not common to get as emotional and moved to tears as I do, but you can also feel this beauty even without knowing the shokunins’ backstories.

Takayoshi Yamaguchi brushing a nigiri at Mekumi. ©Andrea Fazzari

What were the most important life lessons you learned from them?

The importance of ikigai, sense of purpose, keeping it front and center in your daily life. I feel a great sense of admiration for their beliefs and their dedication to lives of purpose. Also, their sense of duty to family members and staff. Sometimes your life doesn’t turn out as you had planned it, but it is still just as beautiful. There’s no reason to worry too much if something does not go according to plan — an example is Terukuni Obana, the surfer shokunin. He had planned to become a train conductor, but instead, sushi and the ocean ultimately provided all that he loves in life, including his wife. The shokunin also reinforced the value of hard work. Especially now, people want to achieve easily — they want to become famous very quickly. But being a sushi shokunin is demanding with extremely long hours every day, and starts early on, maybe at 14 or 15 years old with chores like washing and cleaning the restaurant. This develops a sense of duty and commitment on the path to acquiring the ultimate goal – one’s own sushiya. Perfection is never reached, but striving for it is what is important.

Sushi Shokunin is published by Assouline and available for pre-order from assouline.com. For more of Andrea Fazzari’s work, visit andreafazzari.com.

Featured image: Yasuhiko Mitani preparing for service, surrounded by various cuts of tuna at Mitani. ©Andrea Fazzari

Updated On April 13, 2021