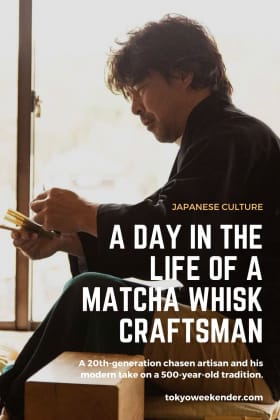

Over 90 percent of Japanese matcha bamboo whisks are made in one small village in northwest Nara Prefecture. The tradition goes back over 500 years, when the Tokugawa Shogunate bestowed 13 families in Takayama village with the Tanimura surname with the right to make chasen. For centuries, artisans worked only at night and passed on their skills by word of mouth to the eldest sons of the family to ensure the craft remained a secret. Of those 13 original families, only three remain. Tango Tanimura is the 20th generation head of one of those three after learning the mastery from his father – just as his ancestors before him.

What is a typical day like for you?

To make one whisk from start to finish takes two hours. Generally though, I make them in batches, working on one stage at a time. There are five stages in total. It’s a more effective method and means I can outsource some stages to helpers around the village, as some are easier than others. If one person focuses on only doing stage one, you can get through about 30 in one day. I have 12 people working for me in this way and they do it mostly from their homes. It’s kind of a lonely business in that way.

“In the past, bamboo whisk craftsmen worked by candlelight at night to protect the method and keep it a secret.”

Of course, sometimes there are last-minute orders or those that must meet a particular deadline. In that case, I make them from scratch as needed. For the most part, my work is focused on the third stage. I start around 9am – quite late, really – but in the past, bamboo whisk craftsmen worked by candlelight at night. This was to protect the method and keep it a secret. For over 500 years, Takayama artisans made chasen in this way and, even now, this is the only place in Japan that makes them. Now, about 70 percent of bamboo whisks sold in Japan are from China, but almost 100 percent of those made in Japan are produced here in Takayama. This is because they kept the know-how here for so long – it didn’t escape to other regions. Even within the family, they were strict about who they would pass the knowledge on to; usually the first-born son.

Why did you choose this job?

Well, it runs in the family. That’s the main reason why. I didn’t grow up thinking, “Oh, this is something I really want to do.” Once I graduated from university I became a salaryman and opened a home accessory store. My parents let me do what I wanted. But when I was 29, I started thinking about how I should take care of my parents as they grew older. So I returned home and started learning how to make whisks. That was about 26 or 27 years ago. I enjoy doing it and I have fun as I work.

There are many types of traditional crafts in Japan but everyone has the same problem when it comes to passing on to the next generation. Children, or young people, aren’t really interested. Also, it’s not very attractive in terms of income and many parents don’t want to force their children into it. So, they ask them to study.

I have kids too and of course I tell them to study hard, but I haven’t talked to them about taking over [the family business]. If either of them wants to, then that’s fine. For me, the work should be fun – or at the very least, the person doing it should feel it’s worth doing. If someone complains about their work, saying how hard it is every day, then the kids won’t want to do it either. One of the most important things is to be confident and do work that inspires them to try it on their own.

What’s the most important aspect of being a bamboo whisk artisan?

The most important thing to keep in mind is, of course, that bamboo whisks are consumable products. So, they don’t last forever but they need to last a long time. To make them last longer, the tines I’m shaving should be as thick as possible to prevent breakage. But on the other hand, if they are too thick, they won’t be buoyant enough and then tips will break off. It’s a balance between making it strong enough to last a long time, but supple enough to avoid breakage.

“Without money a craftsman can survive, but without bamboo, a chasen artisan is miserable.”

In the end, it has to be easy to use for the consumer; that’s my goal every day. In our business, many of our customers are quite upfront about the products. If you buy a chasen at a shop and it breaks or doesn’t perform well, then what do you do? Who do you complain to? Many of my customers are tea ceremony teachers or members of famous tea schools, so they use chasen often. It may sound wrong to express it this way, but I cannot send [my customers] shoddy items. I know where they go and they, of course, know that I made them. It’s a relationship based on mutual trust.

What’s the hardest part of the job?

Getting materials. I don’t go out and cut bamboo stalks myself, I buy them from suppliers. There are fewer people doing that sort of work as many elderly people are retiring. Farmers used to cut bamboo in winter when they had time to spare. But since farming methods have changed, that custom has gradually faded. When bamboo is left unattended, it grows at explosive rates. Bamboo needs to be trimmed regularly or excessive growth will limit sunshine and space. Stalks cluster and don’t grow straight and they damage each other.

Most of the bamboo in this area can’t be used for bamboo whisks. We generally use hachiku; a type of bamboo that has existed in Japan for a long time. Moso bamboo from China – the type from which you can eat the shoots – is the strongest invasive species and makes up more than half the bamboo in Japan now. It makes sense, since people can eat it. They can keep the forests healthy by foraging the excessive shoots, keeping the forests clear. As for hachiku, while you can technically eat the shoots, it’s not common so people don’t grow it. I can’t work without materials, so without bamboo, my skills aren’t of any use. My father used to say that without money a craftsman can survive, but without bamboo, a chasen artisan is miserable. I agree.

What’s the best part about the job?

Meeting new people. Seeing them smile. That makes me happy. Hearing that my chasen are easy to use is the best part. I do tours now too, with demonstrations. People from all over the world come here. I can’t speak English, but I muddle through and it seems to work. Even if I don’t say anything and simply demonstrate my work, visitors watch with great interest. You don’t need words for that. Back in the day, craftsmen would carve away alone in silence. Now I can show people my work and see their reactions in real time. It’s fun to share the wonder when people see it for the first time. I hope people will drink matcha, too. You don’t have to take tea ceremony lessons. All you need is matcha, a bamboo whisk and a tea bowl. Anyone can do it.

“You don’t need words for that. Back in the day, craftsmen would carve away alone in silence.”

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve experienced while working?

One time, a Hollywood actress came here, but I had no idea who she was at the time. She came with her family. They watched me work and tried a chasen-making experience where you weave thread around the base. I remember thinking she was very tall and slim, but couldn’t have imagined she was a famous actress. Anyway, they left and about a week later I got a call from someone in Akita Prefecture, asking me if Stana Katic was still here. I had no idea who they were talking about – I had already moved on, not knowing who she was and having forgotten what had happened a week before. So I told them that no one of that name had ever been here and has no plan on coming here, either. But, I got curious and looked up her name online. I immediately recognized her face and found out she’s the main actress on a show called Castle. It turns out that she had posted a picture of me on her Instagram. The Japanese fan in Akita had seen it, and assuming she was still here, asked if they could visit so they could meet her. I wish someone had told me sooner!

Do you have any advice for anyone thinking about becoming a bamboo whisk artisan?

If someone did want to become a chasen craftsperson, I would first warn them there isn’t a lot of money in it. [Laughs] If they would like to do this kind of work even so, then of course I would encourage them to try. Not everyone can do it, but you don’t know until you try. Previously it was only family members who would make different parts of the process but now locals in the area can do it. However, there is one condition: they have to live nearby. Also, it takes at least 10 years to learn the whole process. That’s why we only teach certain stages. If you only learn stage one, it may take a year. This means the person learning can become proficient quickly, make it a viable job and earn an income. It makes more economical sense for the person learning it. To learn everything and not make any money just doesn’t work because of the time it takes.

Book a Tour: Tango Tanimura doesn’t speak much English, but his demonstrations are mostly self-explanatory. Non-Japanese speakers who want detailed explanations of the process should bring an interpreter. Reservations should be made ideally at least two weeks in advance, to ensure he is available. You can follow Tango Tanimura’s work on Instagram at @leoniki

Photos by Allan Abani

Updated On April 26, 2021