The koto is a slumbering beast. The method of extracting sound from the traditional Japanese stringed instrument shaped like a dragon was left dormant until Michiyo Yagi plugged it in, cranked it up and made it sing her songs.

Traditionally crafted from paulownia wood and strung with silk strings, the koto is a cantankerous instrument. Referred to as a Japanese harp, the weather, humidity and the amount of light in the room can cause the instrument to de-tune.

Just as Leo Fender added pickups to a steel guitar, Yagi electrified her koto to tame the unbridled tones that under less-skilled fingers resonate in the air like the whinny of wild horses.

This winter Yagi released her 12th album, Into the Forest, a mature, measured compilation of original songs that features her vocals for the first time. The album’s opening stanza, played on the electric 17-string bass koto, chimes like a grandfather clock. At the same time, Yagi can make the koto ring like a bell using a poly octave generator – or “stompbox” – typically used for electric guitars. The reverberation that used to fade away now resounds like an organ.

The title track, “Into the Forest,” is a 17-minute, five-part prog rock suite that showcases Yagi’s skill mastered during years of training and playing with world-class mentors. The song moves from weather report jazz rock to an improvised koto and contra-bass free jazz duet to the fuzzy hard rock coda.

Yagi’s production is complex, and the completed form is high art. Most importantly, it reflects Yagi’s decades-long efforts to harness koto music and make it pleasurable to all audiences.

“She has reinvented the instrument”

“She has reinvented the instrument,” says Norwegian drummer and composer Paal Nilssen-Love, who asked Yagi to join select shows on his recent Japan tour.

Yagi grew up surrounded by ceramics artists in the seaside pottery town of Tokoname. Her mother was a talented koto teacher, and the koto was a toy Yagi tinkered with as a toddler. Since Yagi was largely uninterested in the instrument, her mother oversaw her daily, two-hour piano lessons. Then, as a teenager Yagi heard a koto rendition of a Toshiya Sukekawa song. She found the sound fresh.

Her first koto instructor was Satomi Kurauchi, an apprentice of Tadao Sawai. Soon she was taking lessons from Sawai himself, one of Japan’s foremost innovators of koto music. He and his wife Kazue founded the Sawai Koto School, and Yagi was invited to become an apprentice. For two years she lived in the Sawai household. She cooked, cleaned and welcomed guests for the Sawais. She was berated by older students who took her clothes and money.

While many apprentices left the Sawai residence within weeks, Yagi uses a Japanese expression to describe Tadao Sawai as “someone who is above the clouds.” During one performance, she waited in the wings holding Sawai’s extra bridges when she felt his music so transcendent that she found all of her hardships justifiable.

Kazue Sawai was invited to perform at the contemporary classical music festival, Bang on a Can, in New York City, and Yagi accompanied her on stage. There she watched John Cage’s avant-garde composition of half-naked men banging on sheet metal and clay pots.

“That is when I decided I am going to compose and play my own music,” says Yagi.

After graduating from the NHK Professional Training School for Traditional Musicians, she obtained a position as a visiting professor of music at Wesleyan University, to which Cage was closely affiliated. Her initiation to the Western style of education was a “tremendous shock,” as freshmen students not only composed music, but presented their own work on stage.

When Yagi returned home to Tokoname, Japanese audiences weren’t ready for her brand of free jazz koto. No longer affiliated with the Sawai school, lucrative gigs dried up. She took up teaching to make ends meet. “It was a struggle.”

Then in 1999, John Zorn, who Yagi met during her time in the States, invited her to record an album for his Tzadik label. Lugging two kotos and a suitcase she flew to New York City. The resulting breakthrough album, Shizuku, is a vibrant, energetic and at times frenetic display of free jazz.

“That was a significant point in my career, where I could sit in front of the koto and think about my own music,” she says. “Still, it wasn’t an easy album to make.”

“Nobuyoshi Araki said, ‘Your music is not particularly easy to follow. You should make an effort to be accessible to as many people as you can’”

When the album was released, Yagi didn’t see the success that she expected. She did receive a lengthy lecture from provocative photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, who shot the album’s cover art.

“He said, ‘Your music is not particularly easy to follow,’” says Yagi. “’You should make an effort to be accessible to as many people as you can.’”

Jazz pianist Masahiko Sato asked Yagi to compose a koto arrangement and she formed an ensemble with some of her students called Pauwlonia Crush. Around this time she met her husband and producer Mark Rappaport, who she calls “the ray of light who saved my career.”

Tired of using microphones and battling errant sounds, in 2002 Yagi took her 17-string bass koto to a Tokyo guitar luthier who designed possibly the first custom-built electric koto.

Since then Yagi has collaborated with the world’s top jazz musicians. While playing and recording with saxophonist Peter Brötzmann she learned how to tune the koto on the fly as the prolific German bandleader changes keys regularly and without warning. In 2011 she was invited to the preeminent Moers Festival in Germany, where she blew away the audience by performing with two bass players and two of Japan’s top jazz drummers.

The drummers, and regular collaborators, appear simultaneously again on Into the Forest. Yagi has more songs to record and hopes to reform the band Double Trio. This December she has gigs in Tokyo, Ehime Prefecture, Aichi Prefecture and elsewhere in Japan.

She describes her compositions as ancient Japanese battle scrolls. The scrolls can run the length of the room, but if you look at an individual scene, you can see an entire story.

“I want to organize a linear improvisation that would not just seem random, but accessible to the audience,” she says. “I want to energize the audience, inspire the audience in some way, and I am always conscious of doing just that.”

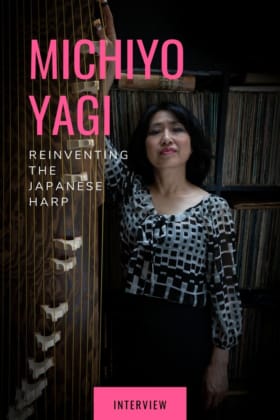

Photographs by David Jaskiewicz

Updated On April 26, 2021