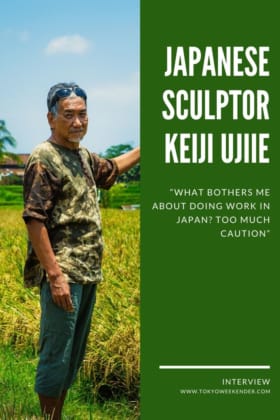

In his quest to give a voice to the natural world, sculptor Keiji Ujiie’s decades-long career has taken him from his native Gunma Prefecture to places as far-flung as the pyramids of Mexico, an artists’ village in Lebanon, and the Indonesian island of Bali – the last of which he now calls home. Long fascinated with the interplay between human beings and our natural environment, Ujiie does not create art for the sake of art so much as he acts as a sort of medium between worlds.

Ujiie’s career took off during Japan’s decadent bubble era of the 1980s and continued to flourish during the 1990s when cash was flush for public art projects such as Faret Tachikawa, which merged the concepts of urban development and art. Despite the excitement of the era, Ujiie found himself gradually disillusioned by Japan’s loss of connection with nature. A turning point in his life occurred when he was commissioned in 2007 for work by a Japanese company in Bali. He instantly fell in love with the island, where he felt that his instinct to create fusions of nature and culture through art had finally found a home.

In Japan for several weeks this past summer, Ujiie sat down with us in the lush rooftop garden of Ginza Six for an in-depth chat about everything from Balinese spirituality to what finally prompted him to leave his homeland.

What inspired you to become a sculptor?

When I was around 15 years old, I used to go often to a Catholic Franciscan monastery located near my house in Kiryu. There were many stone sculptures there, and they fascinated me. I knew immediately that I wanted to sculpt rocks.

“The Japanese concept of nature does have some similarities, but I feel this connection much more strongly in Bali”

What type of materials do you enjoy working with the most?

I sometimes use substances like bronze, but I have always felt rock to be the most responsive. When I was working in Japan, I sourced rock from all over the world, but in Bali I use local materials. In the past, I always started with a square chunk of rock – but I’ve now come to a point in my journey as an artist where I only begin a piece after feeling the energy of each individual stone, and how it relates to its natural surroundings. This has been a change for me.

Did this change happen after you moved to Bali?

It’s certainly gotten stronger there. In Bali, the energetic and spiritual relationship between humans and nature is part of everyday life – particularly for Hindus. The Japanese concept of nature does have some similarities, but I feel this connection much more strongly in Bali.

Have you been influenced by the Balinese concepts of sekala and niskala (the seen versus unseen worlds)?

Absolutely. Some nature you can see with the eyes, and some you cannot – and I have come to understand that the latter is most important. Each of us also carries a piece of nature inside ourselves, which is a concept I am now trying to understand more deeply. Light is the same: metaphorically speaking, there is light that you can see, and light that you cannot. There are things we have lost in Japan that I feel in Bali. When I was working in Japan, my aim was to create sculptures, landscapes and spaces where people could relax and enjoy themselves, but I’ve come to realize that no matter how much money or technology you have, there are certain things you just cannot do – particularly vis-à-vis urban design.

A few of your works in Japan were titled “cenote” – the natural water pools in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula. Why?

The first of these was at a community center in Shinjuku, where I was asked to create a monument. I first wanted to understand the context and energy of the space, so I did research and found that there used to be a water purification plant nearby. I wanted to craft something with a mysterious power connected to water, and what came to mind were cenotes, which the Mayans sometimes used for ritual purification sacrifices. I know it’s slightly occultish, but I had always felt a spiritual energy when I visited the old civilizations of Mexico, and I wanted to try to recreate that.

What is the meaning of your “Cosmic Navel” sculpture in Warabi, Saitama?

This represents the concept of an empty center, or the black hole that birthed the universe. I like the sculpture, but I don’t understand why the local government allocated ¥10 million for it. It’s not like it’s a monument to anything, and nobody seems to be enjoying it.

“Art is being turned into something fashionable, for the purpose of urban development. That’s fine, but I feel that there’s also a deeper spiritual meaning that is being missed”

I’ve been curious about how people are interacting with my sculptures in Japan, so I’ve been visiting them while I’m here, and also checking on them from Bali using Google Earth. Some of the works are not being taken care of very well. I am grateful that I was hired for these projects, but if people are not enjoying the sculptures or spaces in a direct or tactile way, I don’t feel it’s necessary to put them there in the first place.

A few years ago, I visited the “Cenote” sculpture in Shinjuku and saw that a chain had been placed around it, ostensibly for safety. I visited the mayor and asked her to remove it, which she did, but this is another example of what bothers me about doing work in Japan: too much caution, and too many regulations. My statues are for people to touch and enjoy. If a child climbs it and falls off, that’s the parents’ responsibility – it’s not the government’s job to regulate.

I’ve also noticed that there are fewer sculptures in general today, which may be a trend elsewhere as well. Art is being turned into something fashionable, for the purpose of urban development. That’s fine, but I feel that there’s also a deeper spiritual meaning that is being missed.

On that note, another great name was your installation atop JR Sapporo Station titled “A Gathering Place for Fairies.” Can you elaborate?

I wanted to create something to honor the Ainu people, who are indigenous to Hokkaido and have a strong sense of spirituality, much like the Balinese. This is a spot for people to sit quietly or gather with others, and I wanted them to be able to leave the busy train station and enter a portal to a completely different space, where they can convene with spirits and fairies.

What are some of your own favorite works?

Any sculpture that is being loved, and where people are appreciating the unique qualities of the space around it. A perfect example is the “Three Doors” sculpture in Osaka Amenity Park. It’s in a great location, and lots of people go there to enjoy it. In my opinion, this is an example of a successful public art project.

You recently had a health scare, undergoing chemotherapy and then having a stroke. Luckily, you are returning to Bali with a positive health prognosis, but has this experience changed your outlook?

I spent a lot of time thinking while staring out at the same urban scenery every day from my hospital window in Tokyo. I think that cities are starting to look alike all around the world. This might be great in terms of showing affluence, but it has led us into a very dangerous situation vis-à-vis our planet. No matter how technologically advanced we may be here in Japan, nothing is more important than the relationship between humans and nature. Without this, there is nothing. I’ve also realized that we should not wait to realize the preciousness of good health. We can live longer now because of medicine and technology, but we need to consider the deeper meaning of life. In terms of approaching these deeper life questions, I feel that sculpture does have something to say. The world of sculpture is truly limitless.

Photographs by Solveig Boergen

Updated On April 26, 2021