A few years back, Ben Beech would often find himself pedaling past a ramshackle building on his daily commute through Tokyo. It was mostly nondescript, but the hand painted signs out front and pieces of craftwork made from bamboo that hung outside frequently caught his eye. As time passed, his curiosity was piqued: who lived there, and what did they do?

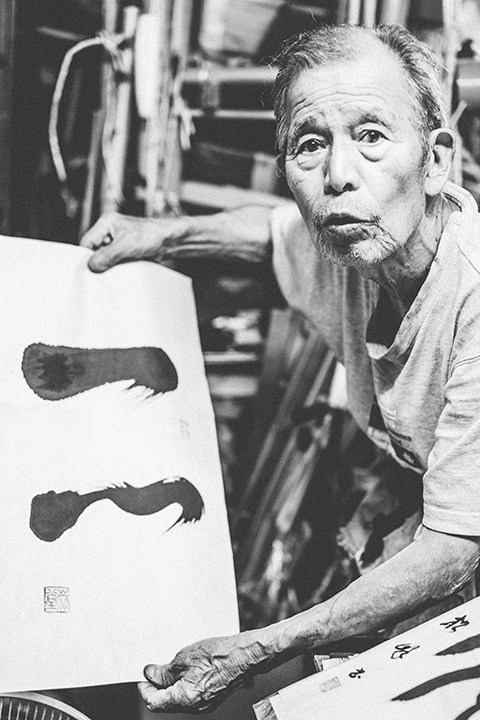

One day, as he cycled past, among the stacks of paper and painted pieces of cloth inside, he saw an elderly man peering back at him. Ben slowed down and got off his bike, and the elderly man beckoned him in. Captivated by what he saw, Ben asked what the place was; a broad smile appeared across the man’s face as he explained that this was his studio, where he painted tenugui – a thin towel used for a variety of purposes – and sumi-e, (Japanese ink paintings) and taught calligraphy. Ben, a professional photographer by trade, had been interested in Japanese calligraphy for some time and was on the lookout for a potential teacher, and he asked him about joining a class. The elderly man agreed, and so began a relationship that bridges some 50 years in age and a considerable cultural divide. It also led to a photo project that’s continuing to this day.

Ben has been studying calligraphy with Sensei [out of respect for his privacy, we will just call him by his title] for about three years now, but at first, his teacher wasn’t sure how hard-working he’d be. “He said that he didn’t think I’d stick to it. He thought I’d give up after a couple of months.” He‘s still a serious student, however – even though Sensei thinks that Ben doesn’t practice enough.

Because Sensei is somewhere between 87 and 89 years old (Ben says that Sensei will occasionally tell him different ages at different times), arranging lessons is a decidedly old-school affair. As Ben explains, “when I want a lesson, I’ll cycle past, pop my head round the door and schedule the next lesson. I’m usually greeted with a smile and a cup of green tea, and then he’ll get out his calendar, which is of course, a paper calendar that he makes each month, bound on some bamboo, and he draws all the lines and writes all the dates himself using a pencil that has been sharpened by hand using a pocket knife … And then I have to stick to it. There’s no ‘Hey man, I’m running late,’ or ‘It’s raining, let’s do it tomorrow’ – there’s none of that.”

Their lessons started with katakana, one of the Japanese syllabaries, and have moved on to kanji, and Ben explains that he will have to learn three different styles of kanji calligraphy – Kaisho (modern Japanese), Gyosho (an older Japanese style), and Reisho (traditional Chinese style) – before he moves on to the more curvilinear hiragana syllabary. It’s the same course of study that Sensei’s own teacher taught him some 60 years earlier. Ben drops by Sensei’s studio about once every two weeks, or more infrequently if he’s busy on photography assignments. They usually spend about three hours on each lesson: about half of that time is spent working on calligraphy, and the other half is spent “talking, chatting, looking at his work, and taking pictures.”

Ben only started photographing Sensei after he had been taking lessons for about a year and a half, but before that, they started to get to know each other better. Sensei is originally from Chiba, and served in the Japanese army during World War II; he was drafted after junior high school. One of his greatest professional successes was painting some of the screens that were used as backdrops at the Kabuki-za theater in Ginza. Now, he sells his painted tenugui and sumi-e at flea markets around Tokyo, and has a few other calligraphy students.

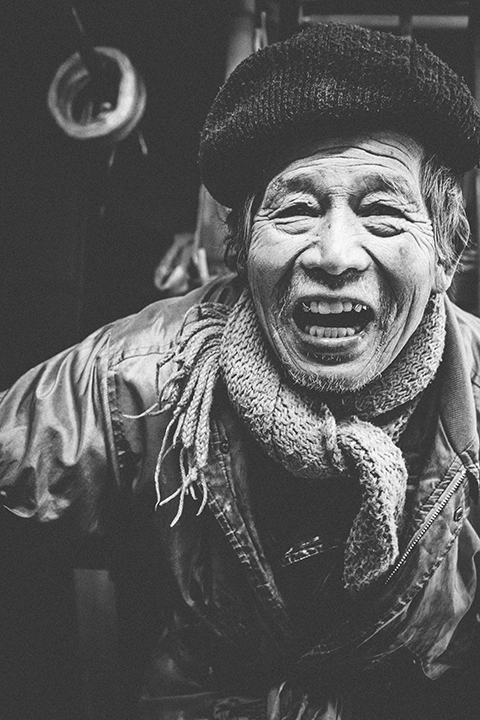

A friendship between the two began to develop over the course of lessons and sporadic trips to galleries around Tokyo, where they would see the works of some of Japan’s greatest artists, from Utagawa Hiroshige to Katsushika Hokusai. Ben also started going to the flea markets with Sensei where he sold his work – one time he helped Sensei drum up business at a flea market held at the foreigner-friendly Tsukiji Honganji temple, writing out customers’ names in calligraphy. And over time, the photographer in Ben was drawn to Sensei’s dynamic personality: “I feel like he’s just such an interesting, energetic character, and when I talk to him, just from his facial expressions and his body language, I kind of feel like I’m getting so much more than verbal exchange, and I really wanted to capture that.”

As he explains, everything in his photos are natural: “Nothing’s set up or posed. I don’t say ‘I want you to get out these pictures and I want you to sit here…’ I’ll have my camera and I’ll say ‘Hey, I’m going to take some pictures today,’ and he’s fine with that. And then he just kind of forgets about the camera.

“If I said to him, ‘Hey, hold the brush up like this,’ he wouldn’t get it. He’d be like ‘Huh? Why?’ But he’s such an animated character that these pictures just present themselves. Quite often I’m there without my camera and I think to myself, ‘Wow, these would have been amazing pictures today.’”

The bond between the two is definitely there – it’s Sensei’s first friendship with a foreigner, Ben explains – but the relationship has its boundaries, which Ben discovered when he asked to accompany Sensei on an excursion to the small town where he comes from in Chiba: “There’s this law apparently that if you’re from Chiba, you are allowed to cut down bamboo in certain public forests. And he goes there every once in a while to gather bamboo. He fills his van up with freshly chopped bamboo and brings it back home to make various crafts. And I thought, ‘Wow, it would be really interesting to go with him and learn how one chops bamboo; also, I just wanted to see his home town.’ And he was like ‘Well, why do you want to come?’ And I replied, ‘I just thought it would be interesting to experience and I’d like to take some pictures.’ And he just said, ‘Kore wa, asobi janai yo!’ [“This isn’t fun and games!”] … That was one time I thought we were not really aligned. I knew it was important to him, and I wanted to see it and experience it, and he made it very clear to me that this isn’t something one can experience for fun, this is something that he has to do – something that he has dedicated his whole life to. At that point I realized how important that work was to him. I didn’t ask him again.”

Their friendship has also led to new discoveries for Sensei – in particular, a kind of food that almost all of us take for granted. One day Ben had gone over to Sensei’s place to help digitize his archive of works. During their lunch break, Ben went to the local combini and got a sandwich and something to drink. “I came back and he saw the sandwich and he was like, ‘What’s that?’ And I said, ‘A sandwich.’ He was staring at the sandwich in amazement. I didn’t think twice of it, and I carried on eating. And I went there two weeks later and he said, ‘So I tried making a sandwich.’ I said ‘What?’ And he said, ‘That thing you ate a couple of weeks ago. I made one … I went to the supermarket. It’s made from bread, right? So I bought some bread, and I bought some lettuce and tomatoes, and it was really good.’ I asked him, ‘Is that the first sandwich you’ve ever had?’ And he replied, ‘That’s the first time I’ve ever eaten bread.’”

As Sensei is approaching 90, if Ben hasn’t had a lesson in a while, he’ll ride by on his bike just to check up on him and make sure he’s doing all right. And he’s the first to say that his experience with Sensei is very different from what he would have had with a younger, more contemporary calligraphy teacher he might have found online: “I really do see him as more of a friend than as a teacher. I also see him more of a teacher in general rather than just a calligraphy teacher. I learn a lot from him. I’m not just learning shodo, I’m learning the way that other people live and think.”

All photos by Ben Beech. To see more of Ben’s photography, visit his website or check out his Instagram feed.

Updated On April 26, 2021