Kimono has long been pigeon-holed as the “national costume” of Japan, and largely ignored by Western fashion academics who view it as an unchanging garment that simply serves the purpose of covering the body. It is clothing, but it isn’t considered fashion.

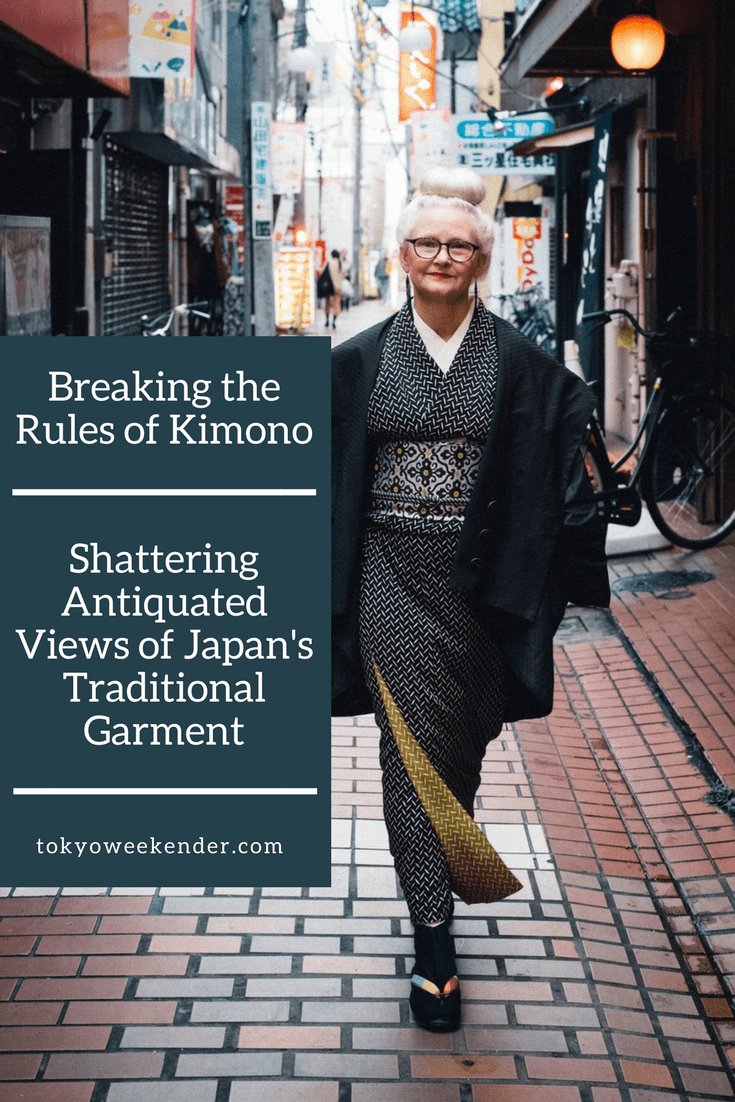

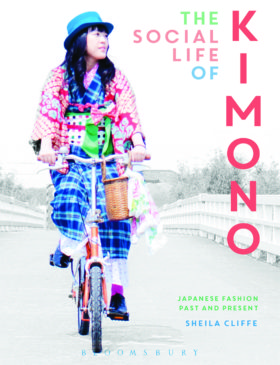

Dr. Sheila Cliffe, who moved from Bristol to Japan in 1985 and is a professor at Jumonji Gakuen Women’s University in Saitama, aims to shatter this antiquated and Eurocentric view of the kimono in her book The Social Life of Kimono. Spoiler alert: she succeeds. Her in-depth social analysis of past and present kimono wearers, as well as makers and craftsmen in the industry, indicates kimono is part of a complete fashion system separate from the West.

Dr Sheila Cliffe

Cliffe’s passion for kimono is infectious, and her deep knowledge on the subject – both academically and aesthetically – is nothing less than inspiring. When asked what kimono means to her, Cliffe tells Weekender: “It’s fashion, very simply. But it’s far more interesting than Western fashion, for a lot of reasons: it’s slow and it’s three-dimensional. It caters to multiple audiences because of that. It’s also much more connected with nature, climate, the seasons and place. Also, a dress or a shirt and pants are kind of a done deal. You can add some earrings or something, but what you buy is basically what you wear. If I buy 50 obi, then that’s 50 different outfits with this one kimono. That’s fascinating to me. Anyone who loves the idea of putting an outfit together will become hooked on kimono.”

On her own kimono-wearing style, Cliffe says, “Contrast works with kimono. I limit the number of colors I use, and those colors are almost always opposites on the color circle. I don’t look at any of the magazines telling you what’s right or wrong. If I look at those, I know I’m going to end up dressing the same as everyone else. When you do that, you lose all the power of expression. I go my own way. I think it’s normal and ordinary, but people seem to think it’s interesting. I suppose dressing is my art.”

Cliffe also mentions that kimono are usually inherited, connecting people across generations. Silk is said to last a hundred years, which is roughly equal to three generations. Given its long life and the fact that silk kimono are kept for formal occasions and thus remain in good condition, being able to wear a hundred-year-old kimono is not unusual. Cliffe explains, “I pick up the old ones and wear them until they fall apart. Unfortunately, I haven’t inherited any from my own mother, but every garment I wear is a story, and I’m just another chapter in that garment’s story. I’m the last chapter – or almost, at least. When I can’t wear a kimono anymore, I cut it up to make kimono collars or recycle it into other things. Each time it changes context, another story is added to the life of the kimono.”

Cliffe’s view of kimono as a fashion item to enjoy and play with may seem obvious now, but it wasn’t always an easily accessible culture. The Internet has played a large role in the spread of interest in kimono, and in turn, bending its rules. Cliffe explains: “Before the Internet, kimono knowledge was trapped within the industry, especially with kimono dressing schools. The schools were keeping it a closely guarded secret, but they didn’t realize that raising the bar to kimono wearing so high was actually strangling the whole industry. It was only because the information started to leak out that the kimono revival could happen.”

The kimono revival found its way through a worldwide boom in Asian culture in the early Nineties. Interest for all things Japanese increased at home, whether it was keeping goldfish instead of tropical fish, or an indoor bonsai garden. Along with that, interest in yukata grew, and from yukata to kimono. As with most fashion movements, young women led the way, but with one difference: the knowledge of how to wear kimono was held by older women. Previously, mothers would have taught their daughters how to wear kimono – now it’s older women teaching younger women who are their friends. “It’s a return to a more natural way of sharing the knowledge,” says Cliffe.

Thanks to the Internet, the interest in kimono has also grown overseas, with people meeting up to wear the garment and discuss its care, how to accessorize it, and more. Cliffe met with one of the groups, Kimono de Jack, in Birmingham. “When I went to interview them, I was petrified at first. I didn’t know what I would be dealing with. But everyone wore their kimono beautifully and had even come up with new ways of tying obi knots, which is fascinating. That’s how far the information has leapt out. And this is without ever having stepped foot in Japan!”

The Web has also helped create a medium for homegrown kimono influencers who reside outside of Japan’s bigger cities. One in particular, Akira Times, breaks the mold of the image of the traditional kimono wearer. He says people are looking for culture in the wrong places because they are looking to the past and trying to preserve it, rather than making something new. He believes in breaking stereotypes and taboos to create something that never existed before. He and Cliffe agree that revising how people frame the kimono is critical for it to remain a fashion item in the future, and the Internet is one way to help spread knowledge and style ideas.

Image by Akira Times

However, even with all the knowledge online, some things still get lost in translation. For Cliffe’s book, she interviewed 50 international kimono wearers and 50 Japanese kimono wearers. The difference in their collections was remarkable. While Japanese enthusiasts had wardrobes with raw silk and komon (a casual kimono with all-over patterns) for everyday wear, international wearers had completely different collections.

“They had so many gorgeous kimono, but they were very formal and with very few uses for them. I understand why, though. They’re coming from the outside, from a visual aspect, and those are the ones that make the strongest impression. I wanted to show that Japan has always had its own fashion, unrelated to the West. I wanted to tell the users’ and wearers’ story. The international wearers only have part of that story, through photos and websites with geisha on them. If you’re going to have a photo taken, then you wear a fancy kimono and that creates a distortion in the data. I wanted to tell the real stories of real women.”

This was how Cliffe’s bilingual project, Kimono Closet, was born. This ongoing project catalogues women’s kimono wardrobes as well as their stories behind certain kimono, their influences, and their challenges. For Cliffe, her social study of kimono has only just begun.

The Social Life of Kimono is available on Amazon.co.jp for ¥3,226. For more info about Dr. Sheila Cliffe and her projects, visit www.kimonocloset.com. Also, find her on Instagram: @kimonosheila and YouTube: Kimono World.

Where to Buy & How to Wear Kimono

While the media would have us believe the kimono industry is dying, Cliffe insists this isn’t the case. “There are some kimono that are only made in certain places because of the weather or because the techniques are so exacting that only a few older people remember how to do it. Those types are endangered, but kimono isn’t dying. It’s changing. There are a lot of new and successful businesses out there. It’s fashion, and fashion changes. There’s nothing wrong with that.” So, where to get your kimono kicks in Tokyo? Here are three recommended spots…

Gallery Kawano

Extensive selection of vintage kimono, obi and haori (jacket), with sizes

available to suit the taller shopper.

Flats Omotesando 102, 4-4-9 Jingumae, Shibuya-ku, www.gallery-kawano.com

Kimono, Remade: Tokyo Kaleidoscope

For those who love kimono patterns and fabrics but aren’t keen on the

traditional way of wearing them, Lia makes stunning modern-day bespoke creations from vintage kimono.

www.tokyokaleidoscope.com

Hisui Tokyo

This school offers lessons not only in kimono dressing, but also tea ceremony, calligraphy and sword training in the heart of Ginza.

5F Koizumi Bldg., 4-3-13 Ginza, Chuo-ku, en.hisui-tokyo.com

Updated On April 26, 2021