Words by John Amari. Photographs by Richard Lee

The islands of Okinawa are having a moment: tourist numbers are climbing as the world catches on to the prefecture’s unspoilt beauty. But aside from its lush green nature and crystal clear ocean, what makes Okinawa so alluring? It’s the people, of course. Weekender recently met three talented locals who represent the colorful and creative energy of the islands. Allow us to introduce you…

The Karate Master: Masaaki Ikemiyagi

Masaaki Ikemiyagi (pictured top) has an easy-going manner, but he was not always this jovial. By his own admission, he was a bit of a tearaway in his youth. Slight but feisty, the young Ikemiyagi was not one to back down from a fight. “I’m physically small. So I wanted to level the playing field, even with people who were larger than me.”

As a teen, he took up karate, joining a dojo (martial arts gym) in Naha, Okinawa, not far from his hometown, Nago City. Ikemiyagi’s parents were worried: wouldn’t karate lead their boy further into trouble? But rather than encourage mayhem, training in karate leads to self-control, explains Ikemiyagi, who is now a master of Goju-ryu karate and teaches thousands of students from around the world. “Thanks to karate, I became humble.”

Inside the karate studio

Okinawa is the birthplace of karate. It is an indigenous art with a heritage that goes back to the local Ryukyu Kingdom (15th to 19th century). “Okinawan karate is more than martial arts,” says Master Ikemiyagi. “It addresses the mind and body and teaches tenacity and dignity. It is a way of cultivating the spirit.” It’s hard to believe that this gentle, welcoming 63-year-old was once a troublemaker. But there is another, more serious side to the Master, which unveils itself after he and I spend a few minutes engaging in kumite (free sparring)…

I throw a jab. Master Ikemiyagi parries and shifts out of the way like a cat. His left hand simultaneously clamps my outstretched arm in a vice-like grip, his right delivers a series of lightning strikes towards my neck. It’s all a blur. Thankfully, this is not mortal combat. Shaken, but still standing, I throw a kick. The Master blocks with his right leg, and, using the same leg, strikes at the back of my standing leg, throwing me off balance. I feel completely at his mercy.

Writer John Amari (left) takes a lesson with karate master Masaaki Ikemiyagi

Master Ikemiyagi has a personality so magnetic that he may as well be 6 foot 5 inches tall. While small in stature, he is built like an ox; he kicks like a mule. When we move to the side of the dojo, where free weights, a punching bag, and a makiwara (a traditional, wooden “punch-pole”) are located, I discover something else about him: “I have a pretty strong punch, you know.” I believe him. His knuckles are calloused and bulbous. And when he punches the makiwara, the ground shakes.

Next, we sit at a low table next to the dojo, which he built himself 37 years ago. I watch him, dressed in a white do-gi (martial arts uniform), as he gently but precisely draws Japanese calligraphy. His posture is erect, his legs folded beneath him. The Master’s favorite saying comes back to me, and it reflects why he loves karate: “When a flexible person defeats a strong person.”

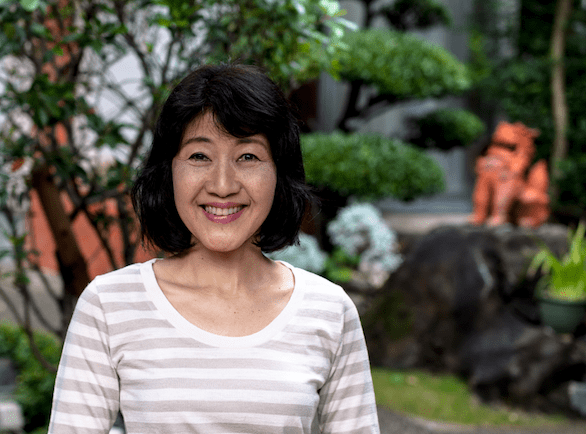

The Culinary Queen: Katsue Watanabe

Katsue Watanabe is on a mission. She wants the world to know the secrets of Okinawan food and longevity. She also wants you not just to enjoy the region’s offerings, but to revel in their unique qualities. “Rather than just saying gochisousama (that was delicious), I want people to also say kusuinatan, an Okinawan saying that means kusurini narimashita (this food was good medicine).”

The people of Okinawa are rightfully proud of their legendary lifespans: the prefecture has some of the highest longevity indices on Earth. Watanabe believes there are two reasons for this. The first is their approach to life: “‘Que sera, sera.’ (What will be, will be.) Whether it’s a good or bad thing, that is our mentality. It contributes to our good health.” The second is Okinawan food. On a large table in Watanabe’s family-run hotel, 50 different items are immaculately laid out. The entire energy count is 585 calories, the equivalent of one anpan (a sweet roll filled with red bean paste).

Where to begin? I reach for a small glass of handmade soy milk. It’s almost like pure white water. I reach for another drink, an Okinawan citrus juice, which is fresh and has a bitter yet enjoyable kick to it. From what I can tell, each item seems like it’s part food, part medicine. Watanabe explains: “Our carrots contain more beta carotene than carrots anywhere else. Over here, you have fish, celery, purple potato, blue papaya…”

Further along, there are scallions, and handama, which is an Okinawan herb that locals refer to as nuchigusui (Okinawan dialect meaning “medicine for the soul” as it aids blood circulation and increases longevity). Light, fluffy pink bread is within reach, so I grab it and break off three pieces. I spread yellow ukon (turmeric), white sesame jam, and blueberry jam on each. It’s a colorful, delicious dance of flavors. The fruit and vegetables are next – Luffa aegyptiaca (Egyptian cucumber), raw mozuku (sea weed), ozenzai (red bean soup), tougan (ash gourd), and yushidoufu (soft tofu) soup. I savor every morsel.

Watanabe tells me that the level of ultraviolet rays in Okinawa, which can be four times higher than in other parts of the country, make for vegetables that are rich in vitamins. Moreover, gusts of wind from the ocean ensure the island’s soils are saturated with nutrients and minerals.

Watanabe’s breakfast is inspired. But how did it all begin? Some 40 years ago, her mother traveled to Europe and the US. To her surprise, she found that many places offered the same breakfast she did in her hotel: bacon, toast, coffee and so on. Rather than continue serving that same breakfast, Watanabe’s mother chose an original approach. For inspiration, she relied on her own mother’s cooking. Yakuzen choushoku (breakfast with 50 pickled items) was born.

Today, Watanabe – who has a medicinal cooking certificate – is the manager of her family’s 63 year-old hotel, the Okinawa Daiichi Hotel. She is also the custodian of her family’s culinary culture, and her customers from around the world come not just to enjoy her meals, but to discover the secret at the heart of good living in Okinawa.

The Pottery Princess: Yumiko Kinjo

Few things are as quintessentially Okinawan as ceramics. The tradition goes back centuries, having reached the Ryukyu Islands via the Silk Road and China. For Yumiko Kinjo, pottery is in the family line. Thanks to her architect father, her home was filled not just with ceramics but also traditional crafts. “When I went to college in Okinawa, I decided to study pottery, and my professors introduced me to different styles. That was how my passion grew,” she says.

At first, Kinjo was inspired to make earthenware as she had a love for monotones. That would change, however, when she entered her forties. “That’s when I started adding colors.” Today, pottery is as much a part of her life as the air that she breathes. Indeed, much of her inspiration comes from the nature and culture of Okinawa itself. “The sunlight is very strong in Okinawa and it affects everything here – the sky and the flowers are vibrant.”

An avid traveler, Kinjo is also inspired by her overseas trips. “I like going abroad to enjoy different types of nature. The colors in Northern Europe, for example, are completely different to those here.” It is little wonder that some of Kinjo’s biggest successes have been overseas, where she has held exhibitions. “The response was great in Taiwan and South Korea. Lots of people say, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this.’”

Prevailing trends are another source of her inspiration. Recently, there has been a revival of traditional styles in Okinawa, which tend to favor monotones, but colors are also back in vogue. Before pottery became a popular art form in Okinawa, urushi (lacquer work) with its bright hues was one of the preeminent crafts. In part due to the soil of the island – “which is soft, just like its people” – pottery began to gain in popularity. “The soil here is gentle, so the kindness of Okinawan people is expressed in our pottery.”

Seven years ago, Kinjo and her co-creators established a workshop and display space in Okinawa called Tituti (www.tituti.net). “The ti in Tituti means te (hand). Tsukurite refers to the artists or producers of the ceramics, while tsunagite is a reference to the visitors who connect with our work.” With non-Japanese and younger visitors on the rise, Kinjo says she would like to see more people taking up the art.

But where do you start? Easy. “Imagine who you want to make the pottery for. It could be a loved one – perhaps your grandma. Then, imagine how they would hold it. Size is really important. It is easy to make the pottery, once you know whom you want to make it for.”

This article appears in the February 2017 issue of Tokyo Weekender magazine.

To learn more about Okinawa’s aim to transform itself into the “next best international resort,” read our Q&A with Takao Kadekaru of the Okinawa Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Updated On January 30, 2023