Whether regarded as a seedy remnant of bubble era nightlife or a functional convenience for couples in need of privacy and discretion, love hotels remain a profitable and necessary part of the Japanese landscape. From cheating lovers, or married couples seeking solace from their compact family homes, to lovestruck youths with nowhere else to go, and overworked businessmen forced to schedule their amorous pursuits, the visitors to love hotels come from all walks of life.

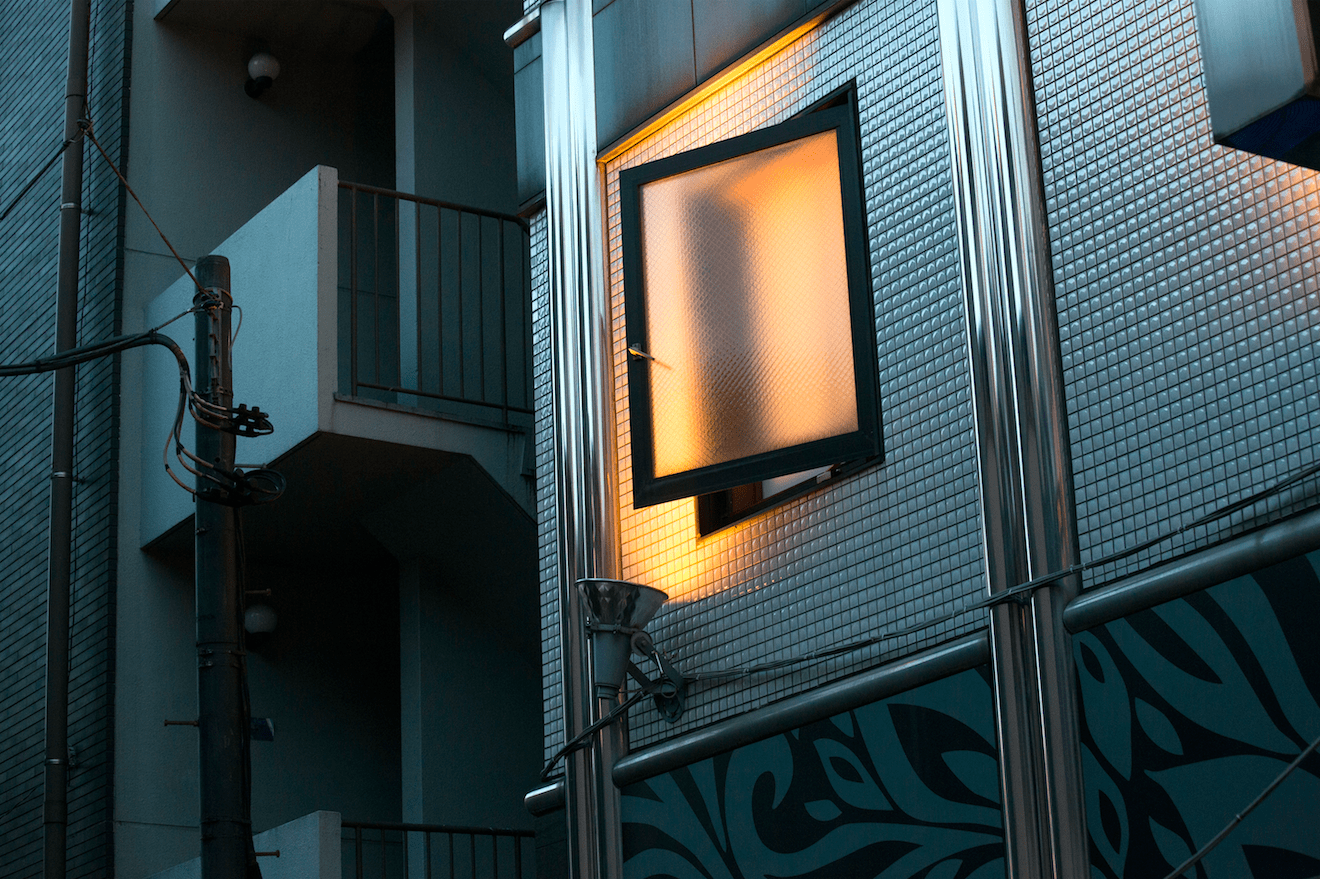

When the establishments first appeared around the 1970s, they were known for their eye-catching decor, themed rooms and titillating playfulness. In recent years, the gaudiness has been toned down, with state-of-the-art facilities and abundant amenities replacing novelty value as the prime selling point. This evolution is a combination of changing tastes and wavering demands as well as the consequence of increasingly complex licensing restrictions. These hotels stand brazenly in plain sight across the country, and yet for many they remain somewhat of a taboo.

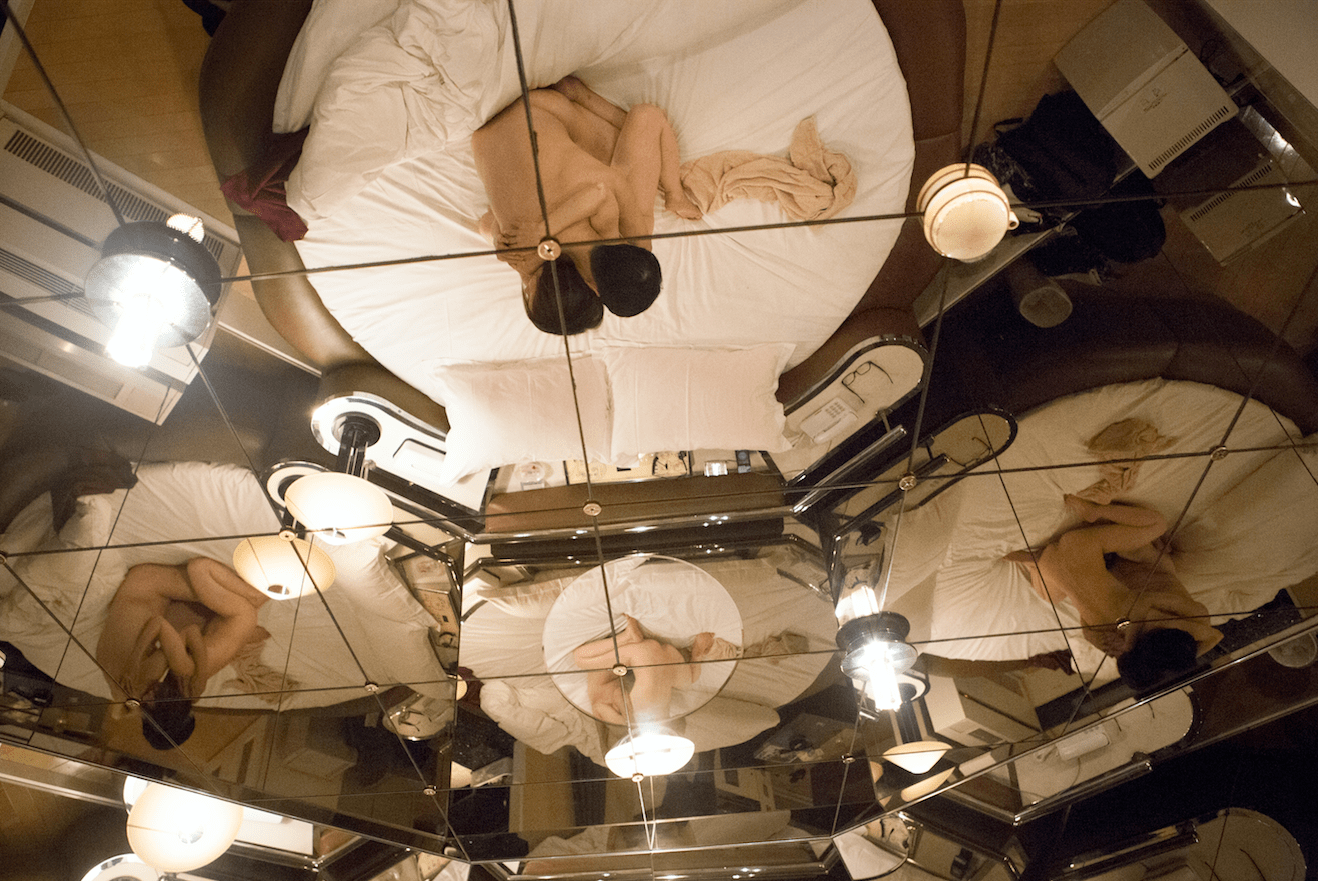

Belgian photographer Zaza Bertrand’s award-winning Japanese Whispers photo series offers an unusual glimpse behind the closed doors, documenting the hotels and the people who use them. Other photographers who’ve focused on love hotels have tended to concentrate their interest on the physical spaces, the kitschy interiors, exoticizing the unfamiliar, and presenting the rooms as no more than quirky locations. However, Bertrand’s pictures selectively capture her own encounters, displaying real slices of humanity with an atmospheric poignancy conveyed in sometimes cinematic composition.

Intimacy plays a prominent role in all of Bertrand’s work, with her portfolio cementing an ongoing theme of interaction and human contact. Having previously photographed young people around Europe, Egypt and Panama, it was in 2011 that she first visited Japan. “People were very open … very sexual and physical in Panama … I wanted to go somewhere that’s not the same,” she explains.

Immediately intrigued by the manners and social behavior of the Japanese people, she soon became curious about the industries dealing with an apparent disconnect between natural desires and people’s ability to openly and honestly express themselves. Love hotels, hostess bars, cuddle cafés, crying therapy – Japan has conveniently created alternative solutions to a multitude of modern day problems, debatably at the expense of nurturing healthy organic relationships.

Bertrand speaks fondly of Japan, inspired by the perfection and attention to detail, which is so different from her own easy-going European upbringing. She is fascinated by what she perceives as organization and control of basic human needs. “I found it interesting … [they] don’t always have a lot of time for basic emotions in [their] life, so there’s been something created just for that,” she says, voicing her thoughts on love hotels and cuddle cafés. “That things like that can be organized, to me that’s not so natural.”

The strangeness of the love hotel system, this pre-planned arrangement of emotions and behavior, is manifested in a kind of tension; one you can surely experience firsthand should you ever find yourself inside such an establishment, and one that intrigued the photographer and is apparent in her images. “You get this pressure when you enter the hotel, you can sense it in the air, people go there for one purpose … everything is kind of fake. Sometimes when you make love, it just happens and you don’t need to plan it, but here it’s all

so specific and predetermined.”

The photographs were taken during two trips to Japan, in 2014 and 2016, before and after the birth of her son. She first stayed in Fukuoka and later in Tokyo, employing the help of friends to try and negotiate subjects who would be comfortable being photographed. They initially approached couples directly at the hotel entrances, offering to pay for the price of the room, but after this proved largely unsuccessful they resorted to advertising online. “I didn’t know what to expect; I didn’t choose the people. Whoever wanted to participate, I photographed; gay people, pretty people, ugly people, it didn’t matter, I just wanted it to be real … not a fictional story.”

Where Bertrand’s previous projects have all included a sense of communal living, depicting lives messily intertwined and connected to their surroundings, Japanese Whispers is unique in its remoteness. The scenes are sparse and detached. The shots featuring models drag the viewer’s gaze to focus on the subjects, allowing us to enter this private space with them. That previously mentioned tension is what ultimately contributes to the mystique of the love hotel; whether your overarching view is positive or negative, that tensity can be read as anything from unsettling anxiety to bubbling anticipation.

Even for a “normal,” steady couple, the time limit and designated location would make an event out of something that generally happens more spontaneously. Whether or not that sounds appealing is down to the individual. There is a general misconception that love hotels perpetuate a separation of love and sex, but to generalize that there is no love inside the hotels is as misguided as to believe love and sex only exist in one definable combination.

The reality of shooting such intimate scenes could easily become awkward or embarrassing for the parties involved, but it was more the unfamiliar way of working that Bertrand found challenging. For her previous projects, Bertrand spent long periods of time together with her subjects, getting close to them until she completely blended in. This uninhibited access allowed her to capture something candid and personal, as she states: “After a while people forget I’m there. I can’t really explain how I do it, but I become invisible, and then I take photographs.” Inspired by the work of iconic French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bertrand is used to waiting for the perfect moment to appear, with scenes changing as multiple aspects come together all at once.

In contrast, the shoots at the love hotels were all pre-arranged: “They were appointments and only one hour each, so a very different way of working; I wasn’t invisible, I was very present in the room.” Some people shyly waited for her orders, expecting her to direct them, for others the thrill of exhibitionism perhaps altered their actions or mannerisms, but Bertrand aimed to capture something as unaffected as possible. She didn’t choose the people or their clothes or even the specific hotels – the models had complete autonomy and thus the series should be considered on the spectrum of documentary photography, without any journalistic intention. “It was more like creating an image, in time and space, of the people who would pay money to go and make love.”

The necessity to be so concentrated on the scene in front of her was a big experience for the photographer who describes some of the process as seeming “like a movie,” the final pictures having a filmic quality enhanced by the low lighting and mood. “I was out of my comfort zone and I really enjoyed it. It’s like a new door that opened for me.”

In addition to exploring this new way of working in her future projects, Bertrand hopes to have the opportunity to show her recent series to a Japanese audience through an exhibition. She’s curious about the reaction she might receive, wondering if people will be shocked, or even interested. Undoubtedly, few people would resist the chance to peek inside such a provocative private world, but moreover, art often brings a chance for people to see everyday details and events presented as something extraordinary or profound. For those who have grown up alongside these places as part of the mundane, or for foreigners who perhaps have only a fleeting interest in the subject, Japanese Whispers provides rare glimpses of both tender intimacy and cold isolation which, in any society, are so often overlooked.

BUY THE BOOK

Japanese Whispers by Zaza Bertrand is published by Art Paper Editions and available for €30.00 (¥3,625) from www.artpapereditions.org (worldwide shipping offered). For more information about and work by the photographer, visit zazabertrand.com

All photographs © Zaza Bertrand

This article appears in the February 2017 issue of Tokyo Weekender magazine.

Updated On November 26, 2021