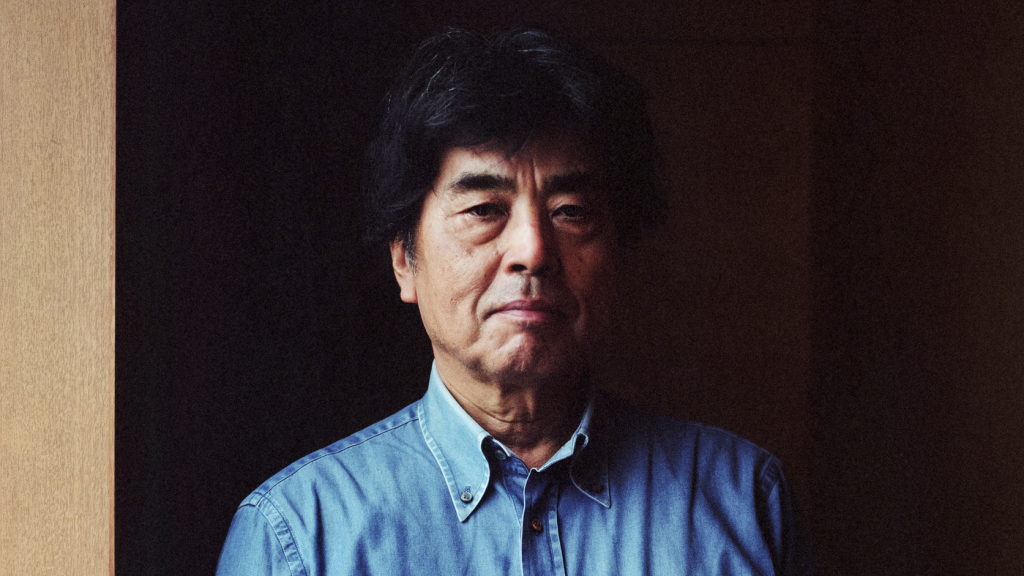

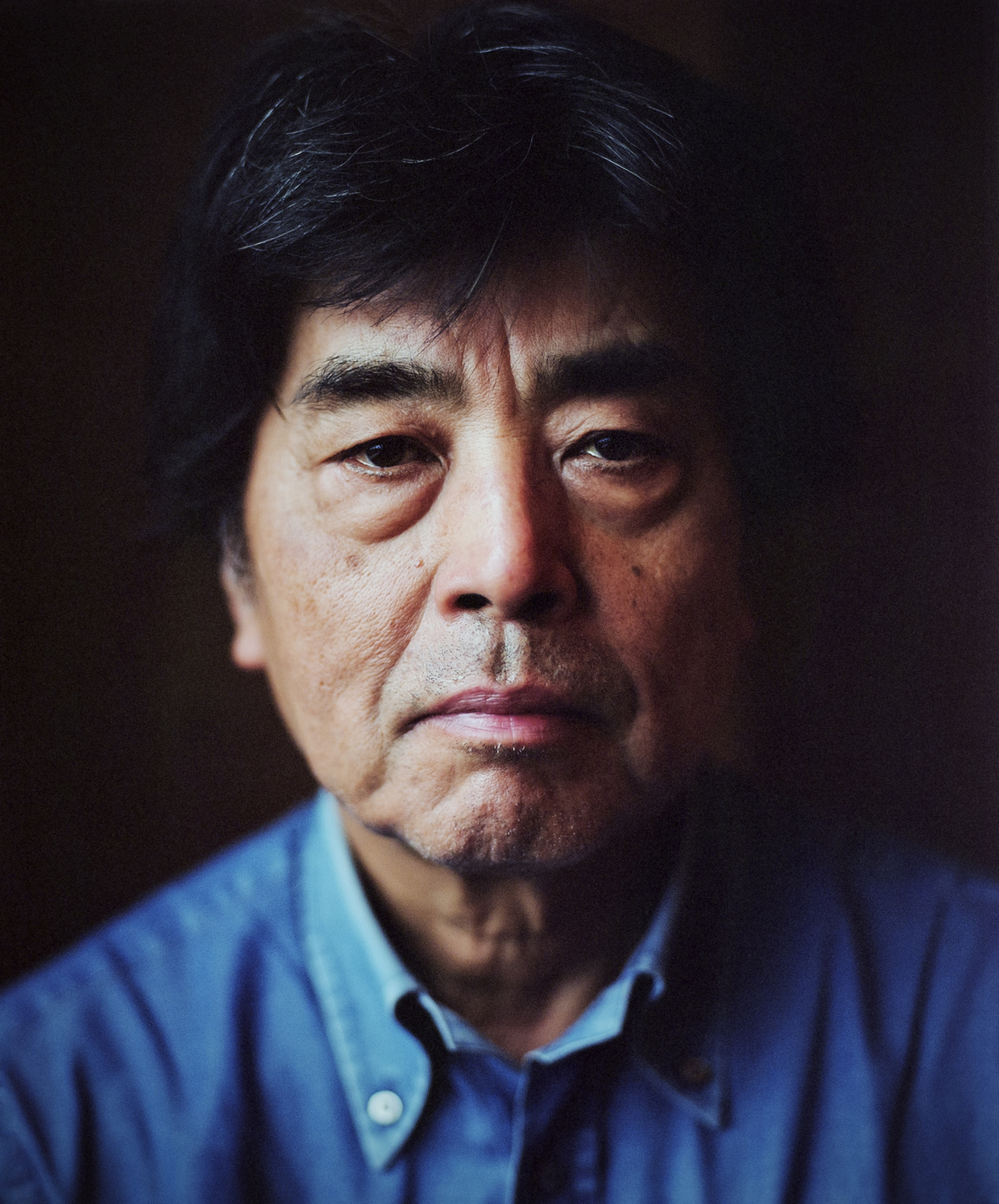

The acclaimed author’s latest book, Japanese Traditional Events, is a marked departure from the noir novels for which he’s famed. He sits down with Annemarie Luck to talk about genre switching, childhood nostalgia, and Trump versus Clinton.

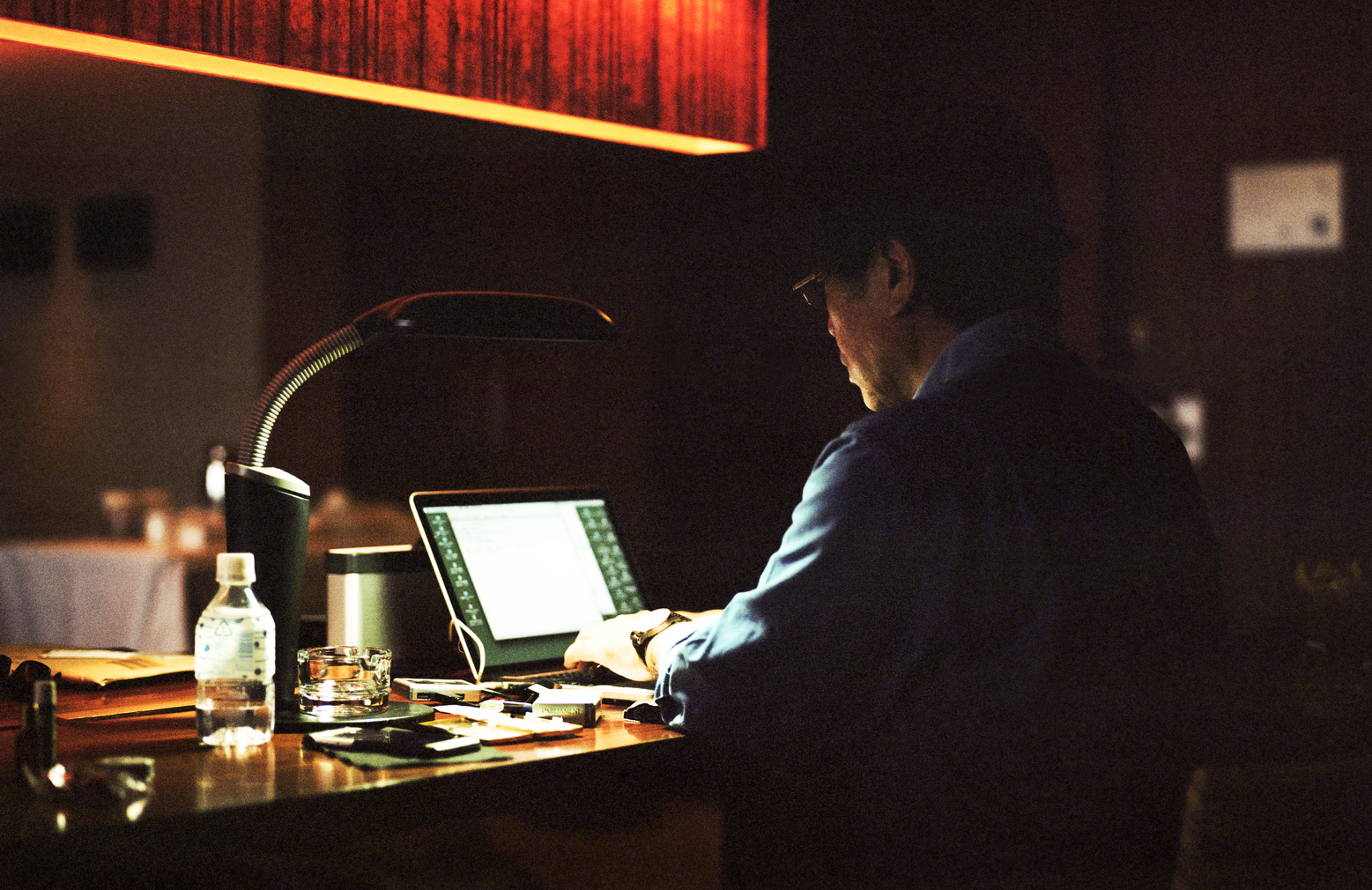

When Ryu Murakami hands me his meishi, the first thing he asks me is do I like the feel of the business card. In the split second between him passing it over and asking the question, I have already rubbed my thumb up and down the white paper and noticed how silky smooth it is. “It’s made from limestone,” he says, with a smile. “No wood, no water.” It’s an unusual way to break the ice, but it does the trick. And as he welcomes me into his workspace, which is actually a suite at a luxury hotel in the center of Tokyo, the mood is easy, calm, and far more relaxed than you’d expect when meeting one of Japan’s most celebrated – and controversial – novelists.

But then again, the 64-year-old has built a career on delivering the unexpected. Since his very first novel, Almost Transparent Blue (1976), which won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize and was heralded as a new kind of literature, the author and film director has shocked and fascinated readers with often grisly, graphic stories that have running themes of sex, violence, and drugs. Now, as I take in the view below of a cluster of treetops, which autumn has burned the colors of fire, I wonder at the unexpected extremes of Murakami’s subject choices. How does he go from creating brutal, psychopathic characters – like the serial killer protagonist in the award-winning novel In the Miso Soup (1997) – to penning his latest work, a non-fiction picture book entitled Japanese Traditional Events (JTE)?

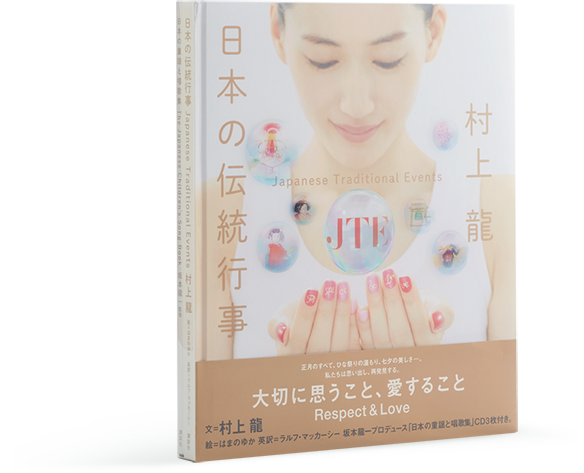

“Writing is my job,” he offers as a pragmatic response. “So while compiling JTE was a different process to writing my novels, it’s not as though I’m not used to writing this kind of thing.” In fact, he tells me he previously wrote a vocational guide for teenagers, before rummaging in some nearby boxes to find a copy. He brings over the hardcover book to show me – it’s called Job Guide for the 13-year-old – and says, “This sold 1.5 million copies.” JTE could also be described as a guide, but in this case the focus is on traditional cultural events in Japan such as the New Year’s custom of visiting a shrine or temple; February’s bean-scattering ceremony (Setsubun); and March’s doll festival (Hina-matsuri). The book has both Japanese and English text, is charmingly illustrated, and comes packaged with a set of CDs featuring famous Japanese children’s songs produced by renowned composer Ryuichi Sakamoto.

There’s a knock on the door. It’s room service, bringing us a trolley of fresh coffee. Murakami pours me a cup, asks if I’d like milk and sugar, and then we take a seat on the sofa to continue the conversation.

In JTE, you write with sentimentality about your childhood. Is there something specific from your past that inspired you to write this book?

When I was growing up in Sasebo, Nagasaki, there was a team of farmers who came all the way from Saga every New Year’s to perform an annual mochi-tsuki ceremony. It involves the pounding of steamed rice into rice cake, using big wooden mallets and a wooden mortar. It was very exciting for us. But around the time I entered middle school, supermarkets started being built, and they would sell ready-made mochi. So the mochi-tsuki team stopped showing up. This is one of the traditions that I feel is now sorely missing from our culture. So I saw value in writing about it, and sharing an impression of what New Year’s looked like when I was little. I also really enjoyed Tanabata, the star festival celebrated on July 7. There were bamboo trees in our backyard and we would write a wish on a piece of paper and hang it on the branches. It’s very romantic.

Do you still do this?

[laughs] Not so much. I feel like these days in Japan, it’s hard to have a wish. Especially for young people, it’s becoming harder to enter a good company and earn a good salary. There are people surviving on meager wages, so even though they might wish for a spouse and a home, it’s hard to have hope under these circumstances.

But isn’t hope about more than just money?

Yes, but in Japan, religion isn’t working very well either. There are some religious people, of course, but many are confused about whether we believe in Buddhism of Shintoism. So we are missing the kind of community that develops when, say, Christians get together and go to church.

You’ve been quoted as saying, “The future of Japan is dark.” How about the future of the world … any opinions on Trump winning the US elections?

It’s better than Hillary [laughs]. What I mean by this is that even though Hillary and her media supporters launched a smear campaign against Trump, American people weren’t really that affected by this strategy. I’m pretty impressed by this.

You know, after Trump was elected, the American translator who worked with me on JTE, Ralph McCarthy, emailed me to say the election had helped him understand why I wrote the book. Having translated some of my novels, he had previously asked, “Why are you writing about New Year’s now?” [laughs] But after the election, he said he realized just how confused America is right now. They’re confused to the extent that they’ve forgotten about their traditions, such as how the country was built, and what the constitution is based on. But because they are politically confused, now is the time to look back on the cultural side of tradition, in the way that I have done with JTE.

But from a foreigner’s point of view, Japan is one of the countries that most upholds traditions…

I feel that developing countries, like Tibet and Bhutan, uphold traditions better than us.

Even though there are still people walking around in kimono in Tokyo?

There are so many people who don’t know how to properly wear kimono.

Have you ever considered a political career, as a means to help improve or change society?

I don’t think I could change it, nor do I think I would want to. You know, I once received a letter from a reader. She was a high school girl. She had fought with her parents, and ran out of the house to escape. She felt there were too many hardships and wanted to die. But she was reading one of my books at the bus stop, and said it made her realize there are many others who feel the same as her. So she thought twice about dying. I think it’s an honor that I can have this kind of influence on someone. To make them feel like they’re not alone. That even though life is not all about the good stuff, it’s also never a good idea to commit suicide. There is always something good if you keep on living.

In the past you’ve spoken about Japanese people’s tendency to hide emotions, which then might explode suddenly and violently. Do you think this is changing at all?

It hasn’t changed much. Maybe we don’t know much about how to express our feelings. Maybe the style of the Japanese language is part of the reason. For example, we still have keigo [respectful language]. Also, there are many different ways to say one word. This is perhaps one of the methods we use to hide our feelings.

In JTE you talk about more foreigners coming to live in Japan. How do you think this is impacting on Japanese culture?

I think it’s positive. One of the reasons it’s hard for Japanese people to get along with foreigners is that it’s simply easier for us to be with other Japanese people. We are islanders so we have little chance to interact with other countries.

Is that why you chose to translate JTE into English? To share with foreigners?

I want people to use JTE almost like a textbook. Or if you are Japanese and working abroad, and if people ask you to explain traditional events, you can give this book to them. Also, there are more foreigners working in Japan now than ever before. One of the guys who delivers my room service, for example, is a refugee from Myanmar. I gave him a copy of the book, and he said it has really helped his community of friends to understand Japan’s culture. There are lots of ways to use the book. It’s not just for children. Right now, I’m also making a list of third- and fourth-generation Japanese communities in the US. I want to send the book to them. I think it will help connect people together.

What are you reading at the moment?

I’ve been reading several books about AI. What I’m interested in is whether AI can also dream as human do.

A new topic for a new novel perhaps?

Yes, I think so…

Japanese Traditional Events (Kodansha Company Ltd) is available for ¥4,860 from Amazon. More information at jte.ryumurakami.com.

All photos by Gui Martinez