Japan has pledged hundreds of millions of dollars in support of Syrian refugees, but should it open its borders?

By Matthew Hernon

Joudi Youssef is one of more than four million Syrian refugees to have left his country since the Civil War began there in 2011. A landowner with a wife, daughter and a baby on the way, he initially had no desire to join any protests. He loved his homeland and had no issue with the government. Then in the spring of 2012 he witnessed an incident that changed not only his outlook, but also his life.

“I saw government forces shooting protesters at point-blank range,” he told Amnesty International Campaigner Kaoru Yamaguchi through an interpreter. “There was a small girl that must’ve been around two years old whose parents were killed by soldiers….For the first time, I understood what was truly happening in my country and decided to participate in the protests with relatives and friends. We went to rallies every day. Then the government tried to have me arrested.

“The police came to my house, but fortunately I was out. A friend warned me about it so I fled by car and hid in another pal’s house for more than 15 days. I was introduced to a broker who I paid $15,000 to help me flee the country. Some people including myself got out successfully but many of my friends failed to do so and were killed.”

The vast majority of his compatriots fled to neighboring countries like Turkey (currently hosting more than 2 million Syrian refugees), Lebanon (hosting more than 1 million) and Jordan (hosting approximately 1.4 million refugees in total, with around half of them from Syria). These countries have struggled to cope with the sheer numbers and life has proved extremely difficult for the refugees staying there. According to Amnesty International, more than 80% are living below the poverty line in Jordan, while in Lebanon the most vulnerable receive less than 50 cents a day for food assistance.

It therefore comes as no surprise that so many asylum seekers, from countries like Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, have attempted to cross the Mediterranean Sea to Europe despite the dangers. Thousands have died attempting it, including Rehana Kurdi, along with her sons Alan and Galib. The tragic image of three-year old Alan lying lifeless on the beach reverberated around the globe. An outpouring of public sympathy for the plight of refugees followed; however, in recent weeks the mood has changed somewhat. Empathy with their cause seems to have waned, particularly after the recent terrorist attacks in Paris. They are facing increasing hostility and suspicion when they arrive in Europe; yet for many there is simply no viable alternative.

Youssef was one of the luckier ones. His broker told him if he paid extra he’d be able to fly out directly from Syria. After a roundabout trip that saw him spend a few days in another country, he eventually ended up in Japan; a nation that’s been extremely generous when it comes to providing international aid, but certainly not one known for opening its doors to foreigners.

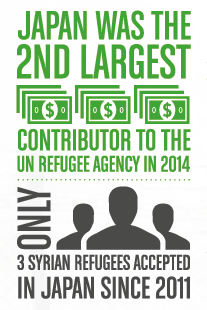

Last year it was the second biggest contributor to the UN Refugee Agency, donating more than $181 million. Since 2011, however, only 63 Syrians have arrived on these shores (according to government data released this August); of them just three have been recognized as refugees. Human rights organizations, like Amnesty and other NGOs, are calling on the Abe Administration to ease its requirements for granting refugee status and make a more substantive gesture to the crisis that goes beyond checkbook diplomacy.

“Of course it’s important to give money, but that isn’t enough,” says Yamaguchi. “It’s about saving lives. We know Japan’s not exactly an obvious destination for Syrians as there’s a huge distance between us both from a geographical and cultural perspective, yet you could say the same about Korea and they’ve received more than 500 refugees. While we see ourselves as a globalized nation, around the world we’re viewed as a closed one.

“Japan needs to open its doors wider for refugees and show them more support. NGOs, including Amnesty International, have put up posters and left out brochures at airports because asylum seekers generally arrive on their own without anyone advising them. They don’t know the procedure, so end up getting a tourist visa, then apply for refugee status later. By that point immigration officials think it’s not an emergency and subsequently not a legitimate claim.”

According to the Immigration Bureau, refugee status is given to citizens who can demonstrate they were persecuted or feared persecution due to race, religion, nationality or political opinion. It’s a very hard thing to prove, especially for someone like Youssef whose passport and documents were stolen en route to Japan.

After Youssef’s latest application for refugee status was turned down, the Ministry of Justice wrote to him explaining the decision. Their statement read “What you did (in Syria) was just to take part in demonstrations or urge your friends to join them. It cannot be recognized that there’s a possibility you’ll be persecuted solely because you are a Kurd.” Like most Syrians here, he’s been granted special permission to stay in the country on humanitarian grounds. It’s a tentative residence permit that he must re-apply for annually. He’s able to continue working and since the interview with Yamaguchi has been reunited with his wife and two kids after support groups and lawmakers took up his case. He’s currently suing the Japanese government, along with three other Syrians, demanding refugee status.

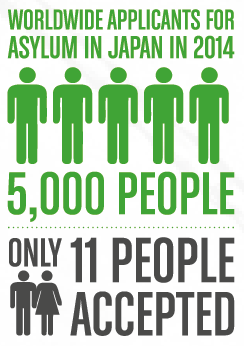

It’s likely to be a tough battle. Despite widespread criticism from abroad, Japan shows no sign of softening its hard-line approach on asylum seekers. Last year out of more than 5,000 applicants less than a dozen were successful and in the future it could become even more difficult if new measures—including a curb on repeat applications—are approved by the government. Ministry of Justice official Hiroaki Sato defended the country’s stringent vetting process, saying, “We’re not looking to increase or decrease the number of refugees coming here, but to ensure real refugees are assessed quickly.” At the UN General Assembly in September Prime Minister Shinzo Abe spoke about the need to tackle domestic issues before “accepting immigrants or refugees.”

Rising tensions and insecurities around the globe have made it easier for his administration to justify its stance. Recent atrocities in countries like France, Lebanon, Iraq, and Mali have heightened concerns and Middle-Eastern asylum seekers are now being painted with the same brush as the terrorists they’re escaping from. In Paris a Syrian passport was found next to one of the assailants and while some claim it was a plant to shift the blame to migrants, others, including many right-wing politicians are using this information to propagandize anti-refugee sentiment and to call for greater restrictions on country borders.

As for Japan, Dr. Toshio Nishi—a research fellow at the Hoover Institution—believes all Middle-Eastern asylum seekers should be blocked from entering as the risks are too great. “Nearby countries that have vast lands like Egypt and Saudi Arabia should be taking in refugees from there, not us,” he told Weekender. “We should only accept those from East Asia. Japan has no way of determining who might be a terrorist from Syria. All refugees from there are not terrorists, but that isn’t the point. The entry of just one would cause huge turmoil here. Misplaced sympathy could kill this country and the Prime Minister would never be forgiven for that.”

While Nishi’s views may sound extreme, many people in Japan agree with him. Yet this a country, Yamaguchi argues, that signed the 1951 UN Convention relating to the status of refugees and consequently has an “obligation” to protect and provide shelter for people like Joudi Youssef and his family, regardless of race or religion.

“It’s the same with all signatories,” she says. “You can’t claim to adhere to the principles of such a document and then pick and choose who you want to accept. A lot of people in Japan don’t know about the convention and fail to recognize the difference between migrants and refugees. They think the latter are just leaving their countries for a better life when they actually don’t have a choice.

“Japan needs more people and refugees can make a significant contribution to society. We’ve seen that with the (11,000+) Indochinese asylum seekers that came here between 1978 and 2005. The current situation’s more difficult and there are many hurdles, but that doesn’t mean we should ignore it. The crisis is escalating in Europe and we’re turning our backs. It’s damaging our reputation.”

Updated On July 18, 2017