Perhaps the earliest example of the concept of “kawaii” (the quality of cuteness in Japanese culture), kokeshi are the traditional hand-crafted wooden dolls produced in the Tohoku region since the 1800’s.

By Chris Zajko

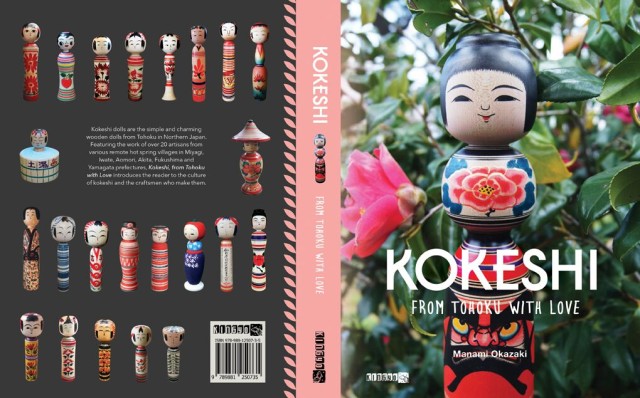

Manami Okazaki’s latest book, “Kokeshi, From Tohoku With Love”, is dedicated to exposing the beautiful world of this traditional craft in the first english language book of its kind. Okazaki provides a comprehensive background about the features of each of the 11 different traditional styles of kokeshi, their production methods and the Tohoku region’s rich onsen culture and lifestyle.

Of particular interest are the 23 interviews (accompanied by some absolutely charming photography) that she has conducted with some a range of “koujin” (kokeshi craftsmen). These men have dedicated their lives to their craft and make some intriguing and insightful comments about tradition, the importance of hard work, passing skills on from generation to the next, spirituality and the allure of the simple things in life.

Stressing the deep tradition of kokeshi culture, one craftsman, Yasuo Okazaki, says the kokeshi dolls have a healing power and “are the soul of Japan.”

In a world of cheap souvenirs and trinkets, another artisan, Kazuo Satou, further elaborates on why the dolls have become especially enchanting amongst people seeking more ‘real’, genuine or exclusive products, “The kokeshi are handmade, not made by machine; one person makes the entire thing, from curing the wood to signing the name on the bottom. You can’t mass produce something like this. You just make them slowly one-by-one.”

Despite a recent resurgence of interest in kokeshi, the modern day industry faces a variety of difficulties. Okazaki writes, “Only time will tell if this craft will live on, or if the humble kokeshi, with its simple design, will become a thing of the past.”

We spoke to Okazaki about her new book and the experience of putting it together.

Question: Why did you to want to write about kokeshi and how did the project get started?

Manami Okazaki: I actually started interviewing kokeshi artisans for a previous book I made on kawaii culture. Many of my interviewees in Tokyo told me to check them out, if I wanted to understand the roots of contemporary kawaii culture and aesthetics. Kokeshi have completely ambiguous facial expressions, you can’t quite tell if they are laughing, smiling, nonchalant or sad, even. For many designers, this lack of distinct facial expressions is one of the characteristics successful kawaii characters like Hello Kitty and Rilakkuma have in common.

My first interview was with Yasuo Okazaki during the kokeshi festival weekend (incidentally, it is coming up in September) and I had the most incredible time. The locals were so above and beyond hospitable, and I was mesmerized by the process of making kokeshi. I was completely in love with the village, the artisan ateliers, the cute kokeshi and the incredible countryside, and wanted everyone to experience it as well.

Q: An impressive amount of research has gone into the book, including 23 different interviews with kokeshi craftsmen across the 6 prefectures of Tohoku. How long has this book been in the making?

MO: Actually, if I planned it efficiently, I probably could have done it quite quickly, as the region of Tohoku itself is not that big. However, I did a lot of side trips to places like Tono Valley, Osorezan, Sakata, Kakunodate and so on, and looked at other aspects of Tohoku culture, so it ended up taking a lot of time. I really had a great time backpacking around Tohoku, and had no desire to rush the experience. I also went to a few of the regions, like Naruko a few times.

Q: You must have met some inspiring people during the research and interview process. Are there any particularly memorable experiences you’d like to share?

MO: The people in Tohoku are so warm, it is almost surreal. They were so genuinely helpful and gracious. Everyday, I was completely bowled over at how kind the people were, and how much they would help me. I even had one random lady drive me around as I was walking along the road, and she was afraid I was going to get eaten by a bear!

After the book was finished, many of the kokeshi artisans sent me handwritten letters with kokeshi to say thank you—usually I don’t even receive an email from interviewees. The folks from YK Suisan sent me a box of fish, and the managers at Horieya ryokan in Fukushima sent me a box of peaches! Given the nuclear disaster is causing the entire region is struggle at the moment, that is the last thing they needed to do. They are truly lovely people.

An example of the traditional “Yajiro” kokeshi

Another memorable thing about the people in Tohoku, is that many of them are actually still alive and talking to me because they were saved from the tsunami by some incredible miracle. One lady’s mum was hauled out of a car, which was washed up a hill while the tsunami wave pulled back. Another stopped off to get a sweet potato and was late for work when the tsunami hit Onagawa. So despite the horror of the disaster, there were also uplifting anecdotes. You would have to be a robot to not be moved by these stories.

Q: You have dedicated a chapter to discussing the distinctive features and historical context of each of the 11 types of traditional kokeshi. Do you have a favorite type? Why?

MO: I like Naruko kokeshi. They are the most orthodox but they are so minimal and striking. To me, they are the most elegantly designed item, and so well balanced. I like the really eccentric looking types as well, like the Hijiori kokeshi.

Q: Do you have a kokeshi collection of your own?

MO: I have about 25 now. I did have a fairly large collection and I completely understand the drive to collect, but I sold most of them for charity at the Japan Expo in Paris a few years ago. So, quite enviably, there are quite a few kokeshi living in Parisian apartments at the moment, enjoying a cool European summer.

Q: Many of the “koujin” (kokeshi makers) talk about the fluctuating interest in kokeshi over the years. What is the market like at the moment? What do you see happening in the future for the kokeshi industry?

MO: After the tsunami, Tohoku became something at the forefront of Japanese people’s consciousness, even if they had never even thought about Tohoku before the disaster. Tohoku products became focused on, and the Japanese media created a bit of a kokeshi craze. It seemed like every time I turned on the TV, there were kokeshi-related TV shows – even ones analyzing the sound of the wood when you turn the kokeshi’s head! Many products with kokeshi motifs (which have nothing to do with real kokeshi per se) sprung up and there were events and exhibitions in Tokyo and Osaka.

The demand for kokeshi is still strong at the moment, I tried to buy one of Muchihide Abo’s and was told it would be a several week wait time, and I went to Naruko recently, and everyone was busy. I wonder if this will last though, as Japanese consumers tend go crazy over trends, and then move on the next thing immediately.

The biggest problem now is that there is demand, but very few successors. It is the same as all the artisan crafts in Japan. Because it takes so long to become professional, young people don’t have the patience to sit through the apprenticeship period. I met three young artisans, but the rest are reaching retirement age, and many of the artisans I tried to get in touch with were in hospital, or not physically able to make them anymore.

Q: Kokeshi were originally designed to be used as children’s toys. Why are people buying them these days?

MO: They are an interior design item, something to decorate the house. The main reasons people buy them now is because they are cute, and they are said to be “healing.” There is something really comforting about having this lovingly crafted piece of wood in your house; it really adds something nice to your space.

I think perhaps people are getting sick of kitsch that lasts a few months, and needs to be thrown out so you can get the next new thing. Kokeshi are amazing as they don’t degrade with age, in fact, they get more characteristic and improve as time goes on.

Also, I think a lot people, including young people, are thinking about whether they want to the get something made in a third world country, in a process that is completely invisible, or something made by hand by a master craftsmen in the Tohoku countryside – these kinds of products with feel-good narratives are gaining popularity now. I interviewed an American artist, Rowland Ricketts for a book on kimono culture. He makes hand-dyed items from natural indigo and he pointed out that products like this have a very different “energy of production” to something made in a factory.

Q: There is some beautiful photography in the book that really captures the essence of kokeshi culture. What are your favourite photos from the book? Is there a story behind them?

MO: My favourite photos are from Toshiyuki Kojima’s studio in Aomori. He passed away a few weeks after I interviewed him, and I am so happy I was able to meet him. I think the amazing thing about books are that they leave behind a legacy. Some kids in the US can pick up the book in a library in 20 years time, and see his studio and imagine what it is like, and appreciate his work.

Q: There are now 2 editions of your book. What’s new in the 2nd edition?

MO: It is not a new book, I just want to make that clear for people who have the first edition. There are 60 more photos, 3 new profiles, new chapters, it is larger, higher quality paper which is from environmentally sustainable sources in Europe, really thick, textured hardcover and a larger format.

Q: Thank you very much for your time! Is there anything else you’d like to add?

MO: Most tourists do the Tokyo – Osaka – Kyoto route, but if you want a perfect mini trip from Tokyo, sitting in hot springs, eating countryside cuisine, hopping around artisan studios in remote villages and ogling spectacular nature will make you extremely happy to be alive!

If you cant make it to Tohoku, there is a new shop in the Skytree Solamachi shopping floor called “Tohoku Standard Market” which sells genuine, handcrafted kokeshi from many of the people featured in my book. Just a heads up – many of the “kokeshi” that you see at the airport shops are actually not kokeshi at all, and are probably made overseas!

You can buy a copy of “Kokeshi, From Tohoku With Love” on Amazon.

Images: Manami Okazaki

Updated On December 26, 2022