A victim of the infamous plane crash is survived by his daughter, who finds peace and preserves his story 30 years later.

By Matthew Hernon

August 12, 1985. A sweltering day on the eve of the Obon Holidays: one the busiest times of the year for all airlines as passengers flock to their home towns to visit family and pay respect to their ancestors. Japan Air Lines Flight 123 from Tokyo to Osaka was one of a number of flights close to capacity that evening. Including crew members there were a total of 524 people on board. Only four survived the flight.

According to the official report, 12 minutes into the journey the rear pressure bulkhead failed due to a faulty repair, resulting in explosive decompression that tore off most of the tail, crippling the aircraft. Heroically, Captain Masami Takahama and co-pilot Yutaka Sasaki managed to keep the plane airborne for 32 minutes before it crashed into a ridge near Mount Osutaka. With 520 fatalities, it remains the deadliest single aircraft crash in aviation history.

As you’d expect with a disaster on such a huge scale there were all kinds of stories of people who hadn’t intended to fly, but ended up doing so while others escaped death because they changed plans. Susanne Bayly was heavily pregnant at the time, so she decided not to travel to Osaka that evening. Her partner, Akihisa Yukawa, did. Roughly a month after the accident, their second daughter Diana Yukawa—now a renowned violinist—was born.

Recognizing Lives and Loss

“Mum’s very candid about what happened,” Yukawa tells Weekender. “She often talks about my father’s bright personality, but apparently he’d been uncharacteristically irritable that morning because he couldn’t get a seat on the Shinkansen. He came home for lunch with sushi; then as he was leaving, he held my sister Cassie’s hand and stroked mum’s belly, saying ‘look after my last creation.’ Months earlier he supposedly freaked out after mum told him I was due on his birthday. He said that this new life was going to replace his own. They never spoke about it again.

“Lots of bizarre, possibly spiritual things were happening around that time. Before the crash there was a blackout in our neighborhood that was never explained. The electricity eventually came back and Cassie started watching her favorite show before it was interrupted by a newsflash. She called mum and asked if it was papa’s plane, but she assumed a domestic flight wouldn’t be that big. Then the passenger list was leaked and the names came on the screen. My dad’s name was at the end. It was one of the only things mum could read in Japanese.”

The fact that Akihisa Yukawa had another family and that he and Susanne Bayly had never been married made things complicated in regards to compensation. His mother supported the girls financially during their younger days, but when she passed away Ms. Bayly decided to contact the airline. JAL reportedly didn’t know about Diana’s existence until 1995. After doing DNA tests (on Diana only as a declaration had been signed by Mr. Yukawa confirming that Cassie was his daughter) the company agreed to a settlement with the two girls in 2001. The real disappointment for Diana, though, is that her family has never received an official apology from the airline for the accident.

JAL didn’t admit liability for the crash (Boeing accepted sole responsibility), but did pay sums reported to be around ¥780 million in “condolence money” to the relatives of those who died. Christopher Hood—author of the books “Dealing with Disaster in Japan” and “Osutaka”—believes the company “basically did all it could in regards to compensation”; however, he feels more compassion should have been shown to some of the victims’ families.

“In many ways JAL acted in a very professional manner,” Hood tells us. “It covered funeral costs immediately and waited until after the 49th day (the mourning period) to discuss compensation. It wasn’t a private company at the time but still had to think about insurance premiums. Speaking to a lot of people involved, the issue wasn’t so much the amount, but rather the business-like approach that was taken. Parents that lost a son were offered more money than those who lost a daughter because men on average in Japan earn more than women. Different values were being placed on human lives and that naturally upset a lot of families.”

JAL’s reputation was severely damaged as a result of the crash. President Yasumoto Takagi resigned, while Hiroo Tominaga, a coordinator of maintenance, committed suicide, leaving a note that read “I’m atoning with my death.” Sales were also badly affected. Unsurprisingly a large number of people were afraid to fly after the accident—domestic passengers dropped by a third—and many of those that continued to fly switched allegiance to ANA.

“Please take good care of the children. It’s 6:30 now, the plane is turning and descending rapidly. I’m grateful for the truly happy life I’ve enjoyed until now.”

With no fatal accidents since 1985, JAL has managed to win back the trust of its customers, yet it knows how quickly things can change. Employees are constantly reminded of their responsibilities and are encouraged to visit and maintain the crash site. In 2006 the Safety Promotion Center near Haneda Airport was opened. It displays wreckage from the flight such as the rear bulkhead, mangled seats, a stopped wristwatch and final notes (isho) written by passengers during the 32 minutes the plane was out of control, including a seven-page message that passenger Hirotsugu Kawaguchi wrote to his family.

Final Words

“Be good to each other and work hard. Help your mother. I’m very sad, but I’m sure I won’t make it. I don’t know the reason….To think that our dinner last night was the last time….Tsuyoshi [his son], I’m counting on you. Mama [a common expression for one’s wife], to think something like this could happen; it’s too bad. Goodbye. Please take good care of the children. It’s 6:30 now, the plane is turning and descending rapidly. I’m grateful for the truly happy life I’ve enjoyed until now.”

After saying goodbye to family members, passenger Ryohei Murakami described what it was like inside the plane. “There’s little oxygen; I feel sick. People are saying ganbatte [do your best]. I don’t know what happened to the plane. 18.46. I’m worried about the landing. The stewardesses are calm.”

First Responders, and Looking Back

It’s remarkable that four people—Hiroko Yoshizaki, her daughter Mikiko, off-duty cabin attendant Yumi Ochiai, and 12-year-old Keiko Kawakami—survived, yet according to testimonies by doctors, even more lives could have been saved if the rescue team had arrived earlier. A U.S. C-130 Hercules spotted the plane 20 minutes after impact, but was ordered to return, allegedly because of a lack of fuel. The Japan Self Defense Forces didn’t arrive at the site until the next morning.

“In some ways you can understand why it took so long,” Hood says. “Issues such as the lack of GPS and the fact that the location was inaccessible on foot would’ve made the search extremely difficult. That said, part of me thinks they should’ve dealt with things better. Panic clearly set in.

“Japanese organizations prefer to rotate jobs so people gain knowledge in a number of fields, which is great in one sense, but it often means there aren’t enough experts. There’s a tendency to turn to the manual in a crisis rather than doing things instinctively. On top of that a lack of equipment was and still is a problem, particularly the shortage of searchlights.”

Thirty years have now passed since the catastrophe. There has been a lot of anger, tears and recrimination during that time, but there has also been a strong sense of solidarity and togetherness amongst the victims’ families, as well as the relatives of victims from other transport disasters such as the China Airlines crash in Nagoya in 1994 and the Amagasaki derailment in 2005. On the 12th of this month a large number of families will gather on Mount Takamagahara to pray for their lost loved ones. Diana Yukawa won’t be with them. She has been up to the site a number of times on the anniversary to play the violin; however, this year she decided to go up a little earlier without her instrument.

“I don’t go up there to tell my father what’s been happening because I feel he is always present in my life anyway,” she says. “I go to the mountain to pay my respects to him, but I don’t want it to be something sad. So many people have told me what a charming, funny, warmhearted guy he was and I want to celebrate that by honoring him in a positive way. At the same time it’s very important to constantly remind people about what happened on that day so that something like this never happens again and all those lives were not lost in vain.”

“I’m looking up to the sky”

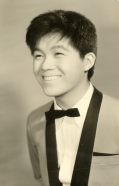

Kyu Sakamoto (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The most famous name on the passenger list was singer Kyu Sakamoto: the first and still only Asian recording artist to top the American Billboard Chart. “Ue o Muite Arukou” (Known to Western audiences as “Sukiyaki”) also reached the number one spot in Australia, Canada, Sweden, Norway and Japan. Diana Yukawa is one of a number of musicians to have covered the track. “I love the sentiment of the lyrics,” she says. “‘Even though tears are rolling down my face I’m looking up to the sky.’ It’s a beautiful song that connects with so many people.” Kyu Sakamoto was 43 at the time of the crash.

Updated On July 19, 2017