Modern dharma, from Zen in the classroom to monks on variety shows.

By Alec Jordan

The varieties of Buddhist practice have run an extremely wide gamut since Shakyamuni Buddha first began teaching in the first millennium BCE in India, and a broad range of traditions have developed since they were first introduced to Japan. From the Zen traditions that most Westerners are familiar with and the dazzlingly complex philosophy underpinning the practices of Shingon Buddhism, to more populist sects such as Jodo Shinshu and Nichiren, the blending of Japan’s native religion—Shinto—and waves of Buddhist thought imported from mainland Asia have generated a rich cross section of practices, rituals, and images over more than 1,500 years.

However, despite this diversity of practices and the lasting influence that Buddhist beliefs have had on Japanese culture, the number of people in the country who would call themselves active practitioners is very small. For the most part, Buddhism only comes into daily life in Japan during funerals or other formal occasions. This is in part due to a series of edicts set forth during the Meiji period – which were actually intended to boost Japan’s native Shinto to the status of a state religion – that officially permitted Buddhist priests to eat meat, drink, and marry. Temples became family businesses of a sort, passed down from father to son (and now, occasionally, daughter), and the main business was handling rites for the dead.

However, if one of the basic principles of the belief system is that there is a regular practice that is meant to be followed, what are some of the opportunities that modern Tokyoites have for engaging with living Buddhism?

Pure Land Cafe

One location is in the trendy neighborhood of Daikanyama, but it doesn’t wear its background too brightly on its sleeve—some Buddha statues here and there, and unobtrusive music, but not much else stands out. Most of the people who do come to Tera Cafe to meet for a meal or a drink aren’t thinking about Buddhism at all, says Shokyo Miura, one of the head priests at the cafe, which is an outreach project of the Jodo Shinshu (“True Pure Land,” or Shin Buddhist) temple, Shingyo-ji. Pushed for a number, Miura said that it would be “about 0.1%.”

But he doesn’t have a problem with that. “This is one of the reasons we set up the Tera Cafe project, in fact. Hopefully it can be a place where young people can come into contact with Buddhist culture, even on a small scale. There are not many opportunities for young people to have access to Buddhism, unless it’s through something like a funeral or another formal ceremony. You’re not going to have many people knocking on the doors of the temple asking for advice if they’re going through a difficult time. This isn’t a problem that is purely unique to Jodo Shinshu either, it’s something that is being faced by Zen temples, Shingon, Tendai, and Nichiren temples as well.”

The main devotional practice of Shin Buddhism is nembutsu, or the chanting of Buddha’s name, but people who are interested in finding out about Shin Buddhism can sign up for classes, offered on a floor above the cafe, in yoga, or sutra writing. (Some classes are also available in English.) Miura says that about 300 people have signed up for classes this year.

Classroom Zen

On a cold, clear morning during the first week of December, a large group of students enter the gymnasium at Setagaya Gakuen and sit cross-legged on black cushions, folding their legs into the half or full lotus position. They shift their weight from side to side until they come to rest, hands resting in their laps in an oval position. During the 40-minute sitting period that follows, the gymnasium is quiet, aside from instructions delivered by a head teacher during the sitting period.

This is the school’s recognition of the weeklong Rohatsu sesshin, a Zen tradition that pays tribute to Buddha’s enlightenment with a period of intense practice: at some monasteries, that can mean as many as 14 hours of meditation per day. At the school, junior and senior high school students practice silent, seated meditation, or zazen, for about 40 minutes each day during the week, and the sittings ahead of class time are not mandatory. But a turnout of about 450 to 500—out of a total student body of 1,400 students—is considerable, given the early hour. As Hisayoshi Nishioka, the religion teacher at the school, explains, a Soto Zen–affiliated high school is a rarity. Most religious private schools around Tokyo, even those primarily for Japanese speakers, have Christian backgrounds, not Buddhist ones. “But parents who are looking to send their children here generally know about the school’s background, and they are choosing deliberately. In fact, some of these students’ parents also frequently come to practice zazen” at open sittings that the school offers to the community a once a month.

Students don’t meditate every day, but a weekly religion class covers ethics, comparative religion, and some basic Buddhist philosophy. Each class begins with a brief practice of seated meditation, and students also visit the school’s Zen Hall four or five times during the year to practice in a more formal setting.

Nishioka sees the strong attendance at the school’s open sittings as a sign that the younger generation is hungry to know more. “I believe that there are plenty of people who do have interest in Zen, for example, but places where they can experience practice for themselves are scarce. So even at the open sittings that we have on campus, I see some younger people, even including some graduates.”

Inspiration from Oregon

As Soto Zen priest Jogen Oishi explains it, he didn’t have a family tradition in Buddhism, and he wasn’t inspired to begin training as a monk because of anything that he saw or experienced in Japan. Rather, it was coming across a “cool” American Zen priest while traveling in Eugene, Oregon, that sparked his interest in learning more about the practice. Following a year of study at the Eugene Zendo and at Shurin-ji in Sendai, Oishi chose to begin formal training, and entered the Zuio-ji monastery in Ehime Prefecture, studying and training for several years before his ordination. He now works at Rinno-ji in Sendai.

True to the spirit of what one might expect from a Zen practitioner, Oishi takes a long view of his nine years of practice. From his perspective, the training and learning process is one that never ends, and while he did downplay the positive effects of meditation (asked about its general benefits, he replied, “nothing”), he said that he has experienced a greater sense of connection to the world around him as his meditation technique has improved.

Returning to the Source

My translator at Tera Cafe had his own perspective on how Japanese Buddhism can reach younger generations, but also how it can enter into a larger dialogue with the world community. The fourteenth-generation son of a temple family from Yamaguchi Prefecture, Shojun Ogi earned an undergraduate degree from a Buddhist university in Japan. He then went on to study at Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, and later did research at Harvard Divinity School. In addition to giving classes, he also works with the US publishing house, Wisdom Publications, bringing Japanese Buddhist texts to the West, while also translating western books on Buddhist thought into Japanese—most recently, David R. Loy’s Money, Sex, War, Karma—and writing his own. He’s also a regular guest on a late-night talk show called Bucchake-ji (Temple of Straight Talk). Featuring five Buddhist priests, the variety show addresses a variety of topics (sex, or drinking, for example) and usually hosts a tarento or two.

As he sees it, one of the larger problems is that the various sects need to return to the basics: “The generation before focused a lot on the importance of the founder of one sect, like Shinran or Dogen or Honen or Nichiren [founders or major reformers of Shin, Soto Zen, Jodo, or Nichiren sects, respectively]. They didn’t put so much of a focus on the fundamental teaching. In that sense, it’s almost like a cult of sorts! I’d say that my generation of teachers feels like we should go back to the more fundamental teachings, and at the same time, discovering the mutual points shared by our different sects.”

And this sharing is something that can take place across religious boundaries as well: “I remember something that I heard the Dalai Lama say when he came to visit the US: ‘If you’re a Christian, and you find a good teaching in Buddhism, please bring it to Christianity: it’s OK, you don’t have to be Buddhist.’ Ultimately, that’s the way I see it. I’m not looking to convert a lot of people to Buddhism. People all have their own way of life, and I don’t mean to control that. But if you find a useful teaching, it should be shared.”

Tera Cafe Daikanyama: teracafe-culture.com

Setagaya Gakuen: www.setagayagakuen.ac.jp (Thanks to alumnus Koutaro Ogi for an introduction to the school)

Bucchake-ji: www.tv-asahi.co.jp/bucchake

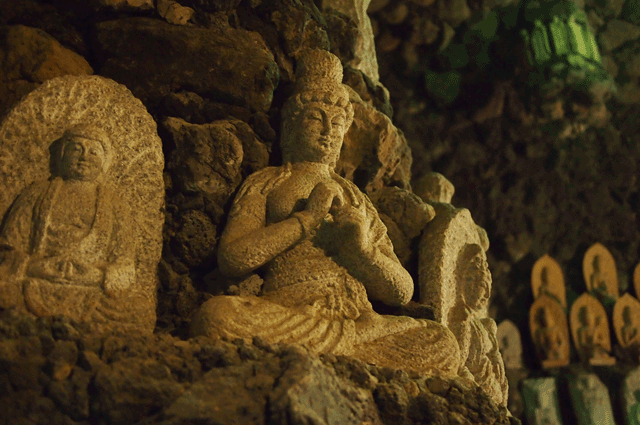

Main Image: In 2012, Tera Cafe set up a temporary temple “installation” in Marunouchi’s Maru Building (Photo ©mecena intercom inc)

Updated On July 20, 2017