Diagnosing the systems that make Japanese health care one of the best bargains in the world.

By Jun Edo Orlanes

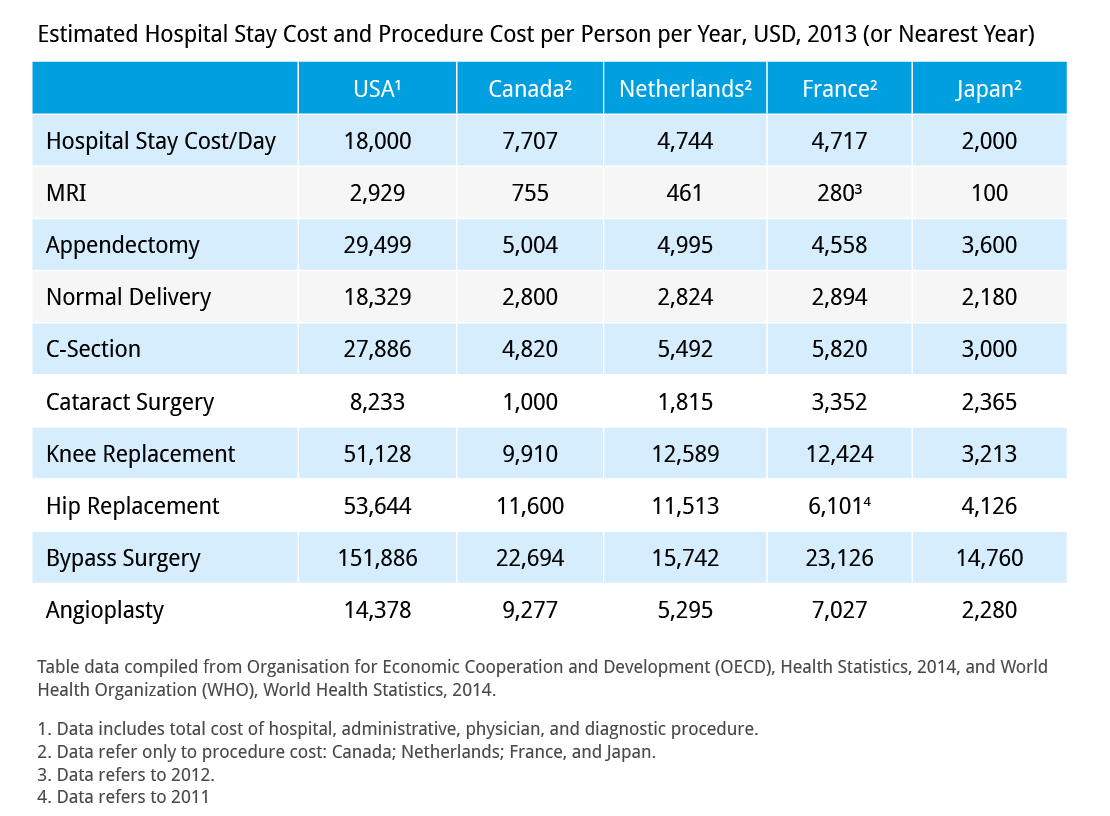

What is good health care worth to you? Depending on the country you live in, that answer may vary widely. In the US, the average citizen spends $8,895 in health costs every year. In contrast, their counterparts in wealthy, developed countries such as France ($4,790 per year per person), or Japan ($4,752 per year per person) pay almost two times as little for health care.

“You get what you pay for” is a common refrain, particularly in the US, but in the case of health care, is this statement true? Are Americans really getting health care that is two times as effective and supportive as the Japanese or French? An observation of the systems in place in both countries shows that doctors being paid well, and they are using the same level of medical technology as France and Japan, and delivering high-quality health care.

“A baby born in Japan today would be expected to live to an average age of 86 or to the age of 82 in France; the same child would live to the average of 78 in the US.”

Japan was the first nation in the Asia Pacific region to develop a comprehensive social insurance program, and France’s health system is set up in a similar manner. In both countries, all citizens are required to have health insurance, either through an employer-based health insurance program or through the national health care program. Those who can’t afford the premiums receive public assistance.

Insurers are all non-profit programs and do not compete. Patients have access to all health care institutions. Most doctors and almost all hospitals and clinic settings are in the private sector, and patients can freely choose their providers.

A comprehensive range of services are covered under health insurance packages, including in- and out-patient care, home care, dental, prescriptions, long-term care, home nursing for the elderly and prosthetics. Cash benefits are given for childbirth. Though very minimal, costs that are not covered include routine physical exams, some dental services and over-the-counter drugs.

When the health care systems of the US, France, and Japan are compared, the cost of care has to be addressed. With Japan and France demonstrating quite clearly that it’s possible to have unconstrained cost-containment and deliver excellent health care, the natural response is to ask what the two countries are doing to keep the costs of health care down.

Upon analysis, three reasons become clear:

Fee schedules

In the US, how much a health care service gets paid depends on the kind of insurance a patient has. This means that health care providers can choose patients with insurance policies that pay them more generously rather than patients covered by lower-paying insurers, such as government-sponsored Medicare co-payment programs under the Affordable Health Care Act. Japan and France, on the other hand, use a common fee schedule, meaning that health care services, doctors, clinics, and hospitals receive almost the same amount, regardless of the patients they see.

Nimble Cost-Control Methods

The health ministries of Japan and France are responsive and have more flexibility to make changes relatively quickly. In both nations, a governing body closely watches health care spending across all types of services. If a specific type of health service is trending faster than they forecasted, the governing body can lower the cost price for that specific service. The two countries also encourage lowering fees through other strategies. For example, governing bodies track how frequently doctors are prescribing generic drugs; if they are not insurance fund representatives will visit the doctor’s offices to encourage them to prescribe cheaper generic drugs. In US, fee schedules are not nearly as flexible, and it can be hard to rapidly adjust the cost of health care services, which are often statutory. Furthermore, Medicare cannot change its fee schedules without approval from the US government.

Private Health Care Cost Dilemma

One of the drawbacks of the US Affordable Care Act is that it limits methods for controlling the high costs of private insurance. In working with private doctors’ clinics, private health insurers continually face a choice between asking doctors to reduce their costs and passing on higher costs to patients in the form of higher premiums. Naturally, the majority of these private doctors find it hard to do the former.

As a result, rather than US hospitals necessarily delivering far more services than hospitals in other nations, the primary reason for higher overall hospital spending in the US is not necessarily that US hospitals deliver more services than hospitals in other nations but that these services simply cost more. Spending in the US is about 85% higher than the average in other, comparatively developed countries, including France and Japan. Even paperwork comes at a higher price: about $900 per person per year is spent on administrative costs in the US, while Japan and France, which use a reimbursement system similar to the US, spend only about one-third of that amount.

In light of recent health care reforms enacted in the US, including elements of the Affordable Health Care Act, it is still challenging to identify with precision why health care costs remain significantly higher. Two other factors stand out in this case: American doctors receive considerably higher salaries than they do in other countries, and the US health care system uses more up-to-date and expensive diagnostic procedures. Costs go unmonitored, and there are so many types of insurance coverage that no one governing body has the strong economic incentive to cut out wasteful practices.

In Japan and France it is not hard to find competent, affordable care for an average citizen with health care needs. Many other first world countries are not as well served. Health statistics for both countries are indicators. Japan’s infant mortality rate is 2.0 per 1,000 live births and France’s is 4.0 per live births.

In addition, Japanese patients have excellent recovery rates from most major diseases. With a low cost universal health care system, about 65% of Japanese patients with chronic conditions can be expected to secure same-day access to a health care provider. The percentage in Japan is compared with about 26% in the US and about 42% in France.

Overall, when we compare the US health care system with that in Japan and France, there are two main factors working to Japan’s and France’s advantage: both countries have relatively healthy populations and an unconstrained universal health care system that serves all its citizens and offers a broad range of choices in hospitals, clinics, doctors, and care facilities. These factors combine to create a happy medium of freedom of choice, a wide safety net, a high quality of life, and a low health care cost per person per year of coverage. A baby born in Japan today would be expected to live to an average age of 86 or to the age of 82 in France; the same child would live to the average of 78 in the US.

Jun Edo Orlanes, MPH, PhD, is principal director and founder of Lean Improvement Institute Consulting Group. His focus is sustaining and spreading lean business practices within the health care industry. He has worked with large health care organizations in the United States including: Kaiser Permanente, Veterans Administration, SutterHealth, University of California San Francisco, and Stanford University Medical.

If you’d like to speak up about your experience with Japanese health care, early next year we will be hosting a survey in conjunction with the NPO DiversityRx. The results of this survey are meant to improve health services to foreigners in Japan.