The dark truth behind the Japanese judicial system’s nearly perfect conviction rate.

By Matthew Hernon

On the surface the criminal justice system in Japan appears to be working very well. Crime rates are low and have been continuously falling for the past eleven years. On top of that the conviction rate here reportedly exceeds 99%, compared with around 93% in the US and 83% in the UK, (according to various sources). So how is such an astonishing statistic possible in a country that doesn’t allow plea bargaining and where wire-tapping and undercover investigation are restricted?

Well, for a start, prosecutors have to deal with low prosecutorial budgets; therefore, they’ll only take cases to court if they’re sure of winning. To get it that far it’s essential they get a confession, which is seen as the “king of evidence” in Japan. According to critics, including numerous nongovernmental organizations, this kind of system not only increases the likelihood that offenders will walk if they don’t admit their crimes, but also makes miscarriages of justice more likely, due to forced confessions.

“The pretrial detention process remains clouded in secrecy,” says Kaoru Yamaguchi, a campaigner for Amnesty International Japan. “Defence lawyers are given more access to their clients than before, but it still isn’t enough. There’s also a lack of transparency regarding the interrogation of suspects. We’ve been lobbying for the introduction of video cameras in interrogation rooms for a while and are hopeful that a bill will be passed next year that will at least lead to certain cases being recorded.

“Another issue is the amount of time detainees are held in Daiyo Kangoku—substitute prisons. In countries like France and Britain suspects can only be remanded for 24 hours without charge (though an extension is possible in both: France for 24 hours, and in the UK for 72 hours, in the case of more serious offences), in Japan it’s 23 days. During that period suspects are often questioned from morning until night by officers pressurizing them to admit their guilt. Under such exhausting circumstances it’s no surprise there are so many false confessions.”

Yamaguchi believes the high-profile trials involving Masaru Okunishi and Iwao Hakamada underline the injustices of a system that seems to treat suspects as “guilty until proven innocent.” The case of Okunishi, who was arrested for the fatal poisoning of five women in the 60s, was originally thrown out because of a lack of evidence. The decision was then overturned and he was sentenced to death because of a confession he said he was forced into.

One of the interrogators put my thumb onto an ink pad, drew it to a written confession record and ordered me ‘write your name here!’ [while] shouting at me, kicking me and wrenching my arm.

Hakamada was released earlier this year following a world record 46 years on death row. The former boxer had confessed to the murder of four people in 1966, before retracting his statement, claiming he’d been coerced into saying he’d done it. He’s now set to become the sixth death row inmate to be retried—the first four were all acquitted—after it was revealed that DNA testing had undermined a crucial piece of evidence in the prosecutor’s case.

“I could do nothing but crouch down on the floor trying to keep from defecating,” Hakamada told his sister. “One of the interrogators put my thumb onto an ink pad, drew it to a written confession record and ordered me ‘write your name here!’ [while] shouting at me, kicking me and wrenching my arm.”

The National Police Agency of Japan insist that “efforts have been made to improve the treatment of detainees,” in recent times, pointing to the separation of custodial and investigative administration, a complaints system under prison regulations and a number of other measures that have been introduced. Critics, however, feel many of these steps are merely superficial and perfunctory.

“New prison laws came into effect in 2007 allowing sentenced prisoners more exercise time and greater contact with the outside world, but in terms of Daiyo Kangoku, little has changed,” says Yamaguchi. “Human rights violations continue to take place, maybe not the kind of physical torture that Hakamada-san had to endure, but psychological torture causing extreme mental suffering.”

Yamaguchi refers to a recent case in the village of Shibushi in Kagoshima where politician, Shinichi Nakayama and 12 others were accused of buying votes in a local election. Detained for 395 days Nakayama was forced to stamp on the names of his relatives. His wife, meanwhile, was ordered to shout her confession out of a window. Motive is seen as more important than actual evidence in Japan; consequently, officers will attempt all kinds of methods to get inside the suspect’s head and obtain an admission of guilt. All the defendants in the Shibushi case were eventually freed due to the suspicious nature of their confessions and a lack of credible evidence.

According to lawyer Yochi Ochia, one of the reasons innocent people have falsely confessed to crimes in the past is because of the Japanese psyche. Speaking to the BBC World Service he said “People traditionally thought they shouldn’t stand up against authorities so criminals confessed quite easily.” Even today there is perhaps some truth to that. In 2012 Ochia posted on Twitter about a man who’d revealed to him in an email that he’d hacked into people’s computers to send chilling messages including threatening to kill children. He stated that his goal was to “expose the police’s and prosecutor’s abomination.” Four innocent people were arrested for the threats, and two of them even confessed to a crime they didn’t commit. The majority of respondents to Ochia’s tweet expressed their anger at the police rather than the perpetrator.

Despite this the prospect of drastic reform isn’t encouraging. In general the Japanese public seem to have a lot of faith in the judicial system and as a result there has been no huge clamor for change. As long as crime rates are low and conviction rates high, the police are deemed to be doing a good job, even if that means sending innocent people to prison.

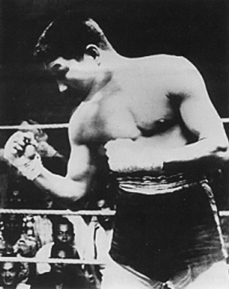

Iwao Hakamada

Hakamada during his boxing career (Photo: Wikipedia/Fair Use)

On June 30, 1966, as the Beatles prepared for their first ever live show in Tokyo, Fujio Hashimoto, his wife and two children were found brutally murdered at their home in Shizuoka. The only suspect was a former featherweight boxing champion named Iwao Hakamada.

With traces of blood allegedly found on his pajamas, Hakamada was interrogated for more than 23 days without a lawyer present. Beaten and threatened he eventually confessed, but then changed his statement, claiming he was forced into it.

During the trial instead of presenting the pajamas, the prosecutors came up with five pieces of bloodstained clothing supposedly found at the miso factory where Hakamada worked. Despite a number of holes in the evidence, he was found guilty and sentenced to death.

In 2007 one of the judges, Norimichi Kumamoto, revealed he’d always believed Hakamada to be innocent, but his vote was overruled 2–1 by the other judges. “The evidence didn’t make sense. The guilty verdict was based solely on Hakamada’s confession,” he said. A year later DNA tests revealed Hakamada’s blood didn’t match the blood on the clothes. He was finally released this year after more than 46 year on death row; however, there remain serious concerns about his mental health.

Masaru Okunishi

Five years before the Hakamada case Masaru Okunishi was arrested in connection with the poisoning of 17 people at a local community center in Nabari, Mie Prefecture. He was accused of lacing bottles of wine with a deadly pesticide that killed five, including his wife and lover, while causing another dozen to fall ill.

The farmer confessed to the crime after five days of interrogation without legal representation, writing in his statement that he wanted to kill his wife and lover to put an end to the love triangle. During the trial though, he retracted his statement, saying he was coerced into it.

The Tsu District Court acquitted Okunishi in 1964 due to a lack of credible evidence and the fact that his confession was unreliable. The Nagoya High Court then overturned that decision, sentencing him to death in 1969. Okunishi has appealed the ruling ever since and in 2005 was granted a retrial after tests concluded that the pesticide in the wine wasn’t Nikkarin-T, the chemical Okunishi had confessed to using.

That decision, however, was overruled and earlier this year Okunishi had his eighth retrial request turned down by the Nagoya High Court. The 88-year-old, now hospitalized, continues the fight to clear his name.

Updated On July 21, 2017