This master motivator was one of the early influences on superstar Kei Nishikori, but first made his mark on the game in the 1980s. Weekender talks with Shuzo Matsuoka about his life on the tour, what it means to be mentally tough, and the inner game of tennis.

By Matthew Hernon

Kei Nishikori’s mentor and tough talking teacher, Shuzo Matsuoka has had a colorful career both on and off the tennis court. He was the first Japanese player to win an ATP tour, famously reached the quarter finals of Wimbledon in 1994 and even had a rule named after him. Now a sports commentator, he’s probably most well known for his passionate motivational videos on his website. So what’s he really like? Weekender recently met up with him in Roppongi to find out.

Let’s start with your own tennis career; what was your greatest achievement in the sport?

Definitely getting to the quarter finals at Wimbledon, because without achieving that, I wouldn’t have the career I have today. The tournament is held in such high regard in Japan that it was my dream just to play there, and so to reach the best eight was beyond anything I could have imagined. Despite Wimbledon being a strict place with many rules, I remember running around wildly after winning in the 4th Round—fortunately nobody complained.

Shortly after your Wimbledon run, you played Petr Korda at the US Open. That match led to the birth of the Shuzo Matsuoka Rule, which allowed players treatment for cramps during a match; can you tell us more about that?

I got cramps in both my legs so I could hardly move; however, because it wasn’t categorized as a condition requiring medical attention, no one could help or even touch me. People were booing and it became a topic of global news, and eventually led to a change in the rules for treating cramps during a match. It was an honor to have a rule named after myself, and it meant my name would be forever recorded in the history of the sport. But to be honest, it was not a rule that I liked, because getting a cramp means you haven’t prepared enough, and stopping the game for a preventable condition is unfair to the opponent.

The Korda match was one of a number of memorable matches you were involved in. Is there one in particular that sticks out?

That would be the match, which I actually lost 6-0, 6-1, in my first year as a professional against Jimmy Connors. I got the chance to play against Jimmy Connors as a wildcard at a tournament in Hong Kong. I’d met him once before when he came to my elementary school and I even got to shake his hand. He’s a really positive guy who loves the game, and he was the reason I started really getting into tennis. To have the chance to face him so early in my career was really exciting, but nerve-wracking at the same time. I was obviously much weaker than he was, yet he gave it everything and didn’t hold back. His professionalism was a great lesson for me, and it motivated me to aim higher.

Who is the toughest opponent you have ever faced?

The player I least enjoyed going up against was Ivan Lendl. He was the number one ranked player in the world at the time we met, and I was just starting out as a professional. He won the coin toss, but he just looked at me and said, “you choose.” It was his way of intimidating me, and it worked. Then, during the 90-second breaks between games when I was resting, he was already up, with a racket in hand, ready for action. He gave me the valuable experience of competing against the world’s best, but at the time, I wanted to leave the court—I was completely overawed.

Players use a variety of tactics to unnerve opponents Pete Sampras, for example, used to avoid eye contact. One incident in particular that sticks in my memory is when Andy Roddick smashed the ball really hard at Kei [Nishikiori] during match play. It was within the rules, but it really rattled Kei, and he ended up losing a game he was dominating until then.

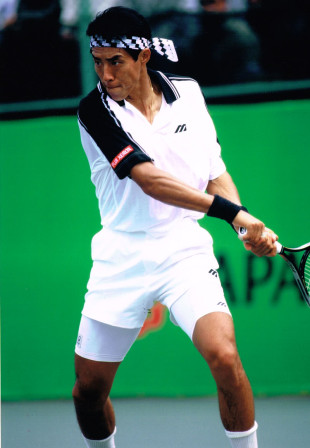

Matsuoka at one of his “Shuzo Challenge” tennis camps. Nishikori went to his first Shuzo Challenge at age 11

You’ve had a big influence on Nishikori’s career. What was your first impression of him as a player?

I first saw him play when he was 11. He was a small kid who didn’t stand out physically, but he was a genius on the court. It was beyond words. I was just starting my Shuzo Challenge camps back then and I was really hard on him. I never criticized his techniques because he already had something special, and I didn’t want him to lose it by making him change his ways. I was harsh on him because I knew he could succeed, and in order to do so, he would need to go on tour. You can’t just be good at tennis to be a top player. You need to be able to expose yourself to English and other foreign cultures. I wanted to reduce his potential struggles as much as possible, so for three years I taught him to speak his own mind and express himself in English. These days his English is really good: he’s very natural and speaks from his heart. But I like to show his old speeches to the kids at my training camps, so they can see that Kei struggled just as much as everyone to get to where he is now.

I presented challenges to Kei at an early stage. I sponsored him for an international tournament for players 18 and over as a wildcard entry when he was just 12. The height and power difference between Kei and his opponents was enormous. I got very angry with him and his partner after they lost a doubles match—not because they lost but because they didn’t believe in themselves. Just because players are bigger and stronger, that’s no excuse for not trying. He got the message and actually won the following year when he was 13. The other day, Kei told me that this was the scariest he’d ever seen me [laughs].

How did you feel seeing him do so well at the US Open?

I was happy, but I thought it would’ve happened sooner. He’s struggled with injuries and I think that’s why he hasn’t reached that elite level many expect him to have reached by this point in his career. I’m proud that he never gave up, and now I think he has the chance to become the best in the world. The top three—Nadal, Djokovic and Federer—are getting older, so the younger players are looking to step into their shoes. There are a number of emerging talents, but I think Kei is the only player with a real advanced style of play and fast pace. His physical condition still needs work, but in terms of technique, he is the best and the world saw that in the game against Djokovic.

Away from tennis you make a lot of motivational videos: what are they all about? Are you as passionate in real life as you are on TV?

I was getting letters from students and businessmen asking for life advice, so I thought I could reach out to them through inspirational videos. I learned a lot about mental training through my life experiences, so I just want to deliver a message while making people laugh. I think I make some good points, but some of the videos are just for fun without any deep meaning [laughs].

I don’t think I’m passionate, really. If you stay with me 24/7, you might think I’m the opposite. I just like seeing people who are working and trying hard because it inspires me and gives me energy. Life’s easier now compared to my days as an athlete, because it’s not about winning or losing anymore. My efforts now go into rooting for people and just delivering what I’m expected to deliver.

Finally, who is the most impressive person you’ve interviewed?

Mao Asada, the Japanese women’s figure skater, is always my favorite. The whole country seems to root for her, not just because she is talented, but because of the effort she puts in. It’s not about the medals or rankings; she gets nervous just like the rest of us and has made mistakes in crucial moments, but we all get excited and sad together with her. She shows weakness at times, and we sympathize with that. I think it’s great.

Interview translated by Mami