Sitting at the far westernmost edge of Japan’s westernmost island, Nagasaki boasts some of Japan’s most unique scenery, history, and culture.

By Robert Morel

This long strip of land, with its twisting coast and hundreds of islands, is home to a range of outdoor activities and breathtaking views both day and night. Thanks to a long history of cultural exchange, Nagasaki developed a unique culture—still distinctly Japanese, but with strong influences from China, Korea, and the West. Even when Japan closed its doors to the West, here in Nagasaki the flow of people and ideas never stopped. Since the first Japanese mission to China in 607 AD, and likely before it, Nagasaki has been Japan’s gate to the world. Whether exploring the countryside, or wandering its cities, the remarkable variety of Nagasaki’s culture, cuisine, people, and scenery offers surprises around every corner.

Land of a Thousand Views

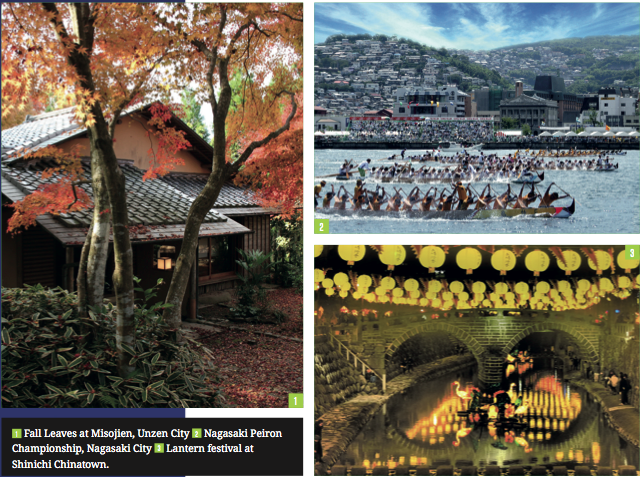

With everything from rolling hills and pastures, lush forested mountains, steep seaside cliffs, and tiny islands and beaches, Nagasaki offers an abundance of scenery and outdoor activities. Home to Japan’s first national park and westernmost marine park, Nagasaki has a long history of valuing and protecting its natural heritage. Unzen-Amakusa National Park on Nagasaki’s southern Shimabara Peninsula has for years been a haven of hikers, birdwatchers, and naturalists. With its unique plant and wildlife, fresh mountain air and impressive views over the hills and sea, not to mention a historic onsen town, it is the perfect place for hiking and relaxing. To the north, the Saikai Marine National Park encompasses more than 400 islands. Here visitors can take a boat through the coves and inlets of the Kujuku Islands, see dolphins and some of the park’s marine life up close at the Umikirara Aquarium, or visit the island of Hirado, with its serene churches, pastoral hills, and dramatic cliffs. To the north, the island of Iki offers tranquil white-sand beaches and expansive mountaintop views.

But not all of Nagasaki’s best views have been shaped by the forces of nature. Ringed by mountains on three sides, the view of Nagasaki City and Harbor is impressive from any angle. Mt. Inasa’s 360-degree observatory offers an expansively spectacular nightscape. The city’s lights reflect and dance in the waters of the harbor, and higher on the hills look like tiny constellations of stars against the dark land and sky. It is no wonder that, along with Monaco and Hong Kong, Nagasaki was ranked one of the three best night views in the world. The Huis Ten Bosch theme park, a meticulous recreation of a Dutch town, is known for its spectacular nighttime illuminations throughout the year. Wandering its medieval-styled streets and canals, lit up in a fantasia of colors, is like stepping into another world, one more colorful and magical than our own.

Millennia of International Exchange

Nagasaki has a long and rich history as Japan’s center of cultural exchange. As far back as 607 AD, Japan sent its first official delegation to China, launching from Nagasaki’s Iki and Tsushima Islands. Being Japan’s closest point to mainland Asia, Nagasaki was for centuries the central waypoint for Japanese diplomats and scholars passing on their ways to and from China and Korea. Returning home, they brought new culture and tastes from the continent. During the Edo Period, Korea sent 12 official delegations to the Japanese capital. Meant in part to show off the country’s wealth and culture, these delegations were elaborate affairs, with diplomats, merchants, scholars and servants bearing goods and ideas from the mainland. At the same time, while Japan was beginning to close its doors on the Western world, Nagasaki Port opened its gates to trade from China. During Japan’s so-called two centuries of isolation, trade with its Asian neighbors flourished and the city was home to some 10,000 Chinese residents.

This long exchange of culture, goods, and ideas with Asia is evident in Nagasaki today, with Nagasaki City’s Shinichi Chinatown standing as its most obvious example. Visitors are welcomed by its vermillion-lacquered Chinese gates, leading to a world of narrow streets, with restaurants and shops selling everything from Chinese medicine to toys to traditional fireworks. In February, Shinichi Chinatown holds the lantern festival, bathing the town in the mysterious glow of more than 15,000 paper lanterns to celebrate the lunar new year. Nagasaki’s ties with Asia, though, are not limited to one neighborhood. Chinese-style architecture is spread throughout the area, seen in temples and bridges, and in the spread of Nagasaki’s unique blend of Chinese and Japanese cuisine.

Though more recent, Nagasaki’s ties to the West date back more than 450 years. In 1550 the first Portuguese ships landed at Hirado, heralding the beginning of Nagasaki’s role as a center of new ideas and technology. With the Portuguese ships came not only new and exotic goods, but new beliefs: missionaries accompanied the merchants. Christianity never became widespread in Japan, but here in Nagasaki, and especially Hirado, belief was strong. After the religion was outlawed in 1612, Nagasaki’s Christians worshipped in secret, passing down beliefs in the form of oratio—religious songs—for more than 250 years. It was not until Japan once again opened to the West and two French priests built what is now Oura Catholic Church that these hidden Christians revealed themselves. Their legacy is visible in the number of churches throughout Nagasaki. But not all new ideas were unwelcome, and when Japan closed its doors to the Western world, it left open a window. For more than 200 years Dejima, an artificial island in Nagasaki Harbor, became Japan’s one port of trade with Europe. Through this trading enclave came new technologies, goods, and knowledge.

In the town of Hirado, the legacy of Japan’s hidden Christians coexists with older religious beliefs. Here you can see the steeple of the Francisco de Xavier Church behind the Buddhist temples of Komyoji and Zuiunji.

After Commodore Perry’s Black Ships forced Japan to open its ports, Nagasaki, poised to become one of the nation’s centers of trade and industry, spearheaded Japan’s industrialization. Thanks in part to merchants and industrialists, Nagasaki became home to Japan’s first modern coal mine, first giant electric crane, and the center of Japan’s shipbuilding industry. Thomas Glover, one of the leading traders of the time, offered arms and support to the Choshu and Satsuma clans who would eventually usher in Japan’s Meiji Restoration, becoming leaders of a new, more open, Japan.

Nagasaki was not only a center of trade. In the summer months, wealthy Europeans and Americans from as far away as Shanghai flocked to the onsen town of Unzen. With its cool mountain air, hot springs, and lush scenery, Unzen was a perfect summer retreat. Here was one of Meiji Japan’s first true resort towns, complete with hotels and camping—even dances and Japan’s first public golf course.

Today, Nagasaki’s churches and the well-preserved relics of Japan’s Meiji industrial revolution are now tentative World Heritage Sites, while many of the merchants’ homes and lifestyles have been preserved in Nagasaki’s Glover Gardens. Thanks to this long history of international exchange, Nagasaki has a very welcoming and open atmosphere. In fact, it is a point of pride in Nagasaki, this willingness to accept people and ideas from all over the world.

Fusion Cuisine ahead of Its Time

With its abundant nature and long history of interaction with different cultures, it is no wonder that Nagasaki has such a varied and unique cuisine. Home to a long shoreline and innumerable inlets, coves, and islands, Nagasaki boasts Japan’s second largest catch and a stunning array of seafood. On land, born of Nagasaki’s soil and rich pastures come a range of vegetables—it is Japan’s second largest producer of potatoes—and the newly famous Nagasaki wagyu beef. Virtually unknown until winning top prize at the 2012 “Wagyu Olympics,” Nagasaki beef has become one of the most sought-after varieties of wagyu. The mineral-rich pastureland of Nagasaki gives this perfectly marbled beef a softly savory taste.

Nagasaki is best known, however, for its unique cuisine, which mixes influences from Japan, China, and the West. Nagasaki champon—a thick and filling ramen-like noodle soup heaped with seafood, meat, and vegetables—and the Sasebo burger are excellent, and hearty, fare. For a more cultured fusion cuisine dating back to the Edo period, Nagasaki offers up its famed shippoku cuisine. Originating as a type of home cooking in Nagasaki’s Chinese quarter, as the style spread it evolved into a lavish banquet. Shippoku is served in a family-style setting, with diners sitting around a special round table to help foster a sense of sharing and closeness among the diners. Now incorporating Japanese, Chinese, and Western influences, shippoku symbolizes Nagasaki’s mix of cultures more than any other cuisine does.

With such a variety and depth of history and culture, such an abundance of beauty and nature, Nagasaki takes hold of the heart and imagination. To visit Nagasaki is to experience not only the essence of Japanese culture, but to see a place where it has coexisted and mixed with others from around the globe. It is amazing to think that this strip of land on the westernmost edge of Kyushu is one of the most truly international places in Japan. And what once took merchants, missionaries, and scholars weeks and months of travels is now just a short flight away.

Updated On December 26, 2022