Travelers during the Edo Period may not have consulted timetables or bought eki bento for their train rides, but they would have found that getting around the country could be almost as pleasant and convenient as it is now, thanks to a historical system of roads called the Gokaido, or Five Routes.

by Alec Jordan

One of these five is the Nakasendo Way. Like the four other Routes that make their way through the central part of Honshu, the path of the Nakasendo itself dates back to well before the beginnings of the Edo Period in the 17th century. However, it was the Edo Period practice of sankin-kotai that transformed the roads into the well-walked travel arteries that they became during this historical period. Sankin-kotai was a political institution that required the daimyo (the local lords) of Japan to spend one year in their homeland and one year in Edo. Given that there were hundreds of daimyo traveling to and from the capital throughout the year, the safe and easy passage of these large groups was a top priority.

Tokugawa Ieyasu ordered the beginning of the work on the roads, but it was finally his great-grandson, Ietsuna, the 4th Tokugawa shogun, who oversaw the formal establishment of the Gokaido. The work on the roads was extensive, and the end results were even more impressive. Where preexisting roads had already been in place, they were improved and made easier for travel by foot, horse, or cart: they measured 11 meters (36 feet) wide, and were covered by a layer of sand and gravel (or in some cases, paved with stone). Finally, given the long tradition of the Japanese attention to comfort, tall trees were planted alongside the roads, affording travelers natural shade.

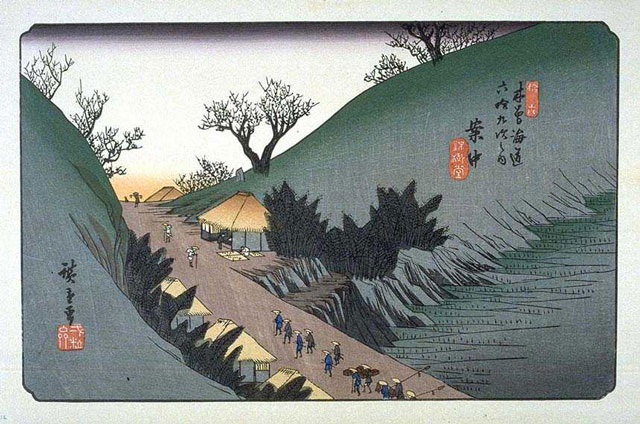

Initially used by couriers as they delivered messages across Japan, the post stations along the routes of the Gokaido grew into larger stopping points, and in some cases, eventually flourished into post towns that offered all manner of refreshment and entertainment. In the second half of the Edo Period, religious pilgrims became a common sight on the roads. While many had were quite devout—the great shrine at Ise was a popular location for pilgrims—the fact that religious travelers were given permission to travel freely may have swelled the ranks of pilgrims with more “casual” believers. Artists and writers also took their own journeys on the Five Routes, and shared their experiences in words and images—many of these accounts remain famous today, such as the 53 Stations of the Tokaido by Hiroshige and the poetry and recollections of famed haiku poet Basho in his The Records of a Travel-Worn Satchel and A Visit to Sarashina Village.

A modern day station on the Nakasendo Way (Photo courtesy of Walk Japan)

The Nakasendo Way is the longest of the Five Routes, stretching 530 km (329 miles) and passing by 69 post stations on its way from Edo to Kyoto. If you were to traverse its length now, you would be going through the present-day prefectures of Saitama, Gunma, Nagano, Gifu, and Shiga on this “central mountain route,” as Nakasendo can be translated.

Along the way, there are many stops that can make the travel experience all the more pleasant: hot springs, spectacular views of the mountainous areas of the Japan Alps region, and small ryokan along the route, serving a variety of local dishes. Many widely used roads and highways run along the same historic route as the Nakasendo, and sections of the route still possess much of the same scenic charm that they did centuries ago. Walks along stretches of the Nakasendo are a popular travel experience, but as a group from the British School in Tokyo found out for themselves, it is a rare thing indeed to try and run the length of this historic route.