by Jay Revelle

Well known as a city steeped in history, Kamakura sits affectionately corralled by its mountainous landscape and a meandering ocean breeze—a place of refuge for those seeking time away from the concrete culture of Tokyo. As if they were Kamakura’s official spokespeople, the iconic Daibutsu (Great Buddha) and famous Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū shrine often provide visitors with their first peek of this beautiful city, supplying them with dramatic and immediate recognition of Kamakura’s historical importance.

Yet behind the scenes, many pieces of Kamakura’s historical puzzle wait to be assembled into the bigger picture. While the more popular attractions dutifully bask in their given limelight, other areas silently wait in the shadows, anxious to welcome those enlightened enough to know of their existence. These locations are so substantial that the city itself has made 23 different applications to UNESCO for areas deemed worthy of a World Heritage designation. When it comes to Kamakura, the old adage, “There’s more than meets the eye,” definitely rings true.

While one may have quite the rapport with Kamakura’s more visible attractions, a trip to the following locations might be cause to rewrite the book of experience, perhaps giving further depth to the sense of how magical and mystical Kamakura really is. Perhaps another trip is in order?

Wakae Island

Kamakura’s Ancient Artificial Island Port

Unknown even to some locals, Wakae Island, or Wakaejima, sits alone and silent, far away from the limelight of Kamakura’s main strip, tucked into the east end of Zaimokuza Beach. This is Japan’s oldest artificial island, reclaimed from the sea in the year 1232.

Originally, the island was intended for use as a port, breakwater, and mooring station during periods of bustling marine trade, meaning that it is actually an ancient harbor. The bay is too shallow for many ships to navigate, and the area’s strong southern winds are still sometimes very hazardous, understating the need for somewhere local and safe to call port.

Its method of construction is somewhat simple—pile enough rocks into a shallow area and eventually you will have yourself an island. Large stones were laid underneath as foundation and smaller stones shaped the surface. Most of the materials were imported from the Sagami and Sakagawa rivers, as well as from Izu Peninsula. The port is said to have been used until the end of the Edo period, when it was finally abandoned.

Nowadays, the island sits barely above the water’s surface, and its 200-meter wide girth can only be seen during low tide. Besides the pebbles, a few ancient pilings are all that remain, and on the beach the site is commemorated with a large stone edifice and a separate signboard, explaining the history of this ancient effort at reclaiming land from the sea.

The Seven Passes

The Gates to Kamakura

As the topography of Kamakura is like that of a natural fortress—flanked on three sides by mountainous terrain and on one side by the ocean—the Kamakura shogunate saw the need to allow traders access to the city, while at the same time providing for the safeguard of such entrances by making them easy to defend. The answer was the Seven Passes, otherwise known as the Nana Kiri Doshi, which consist of the Asaina Pass, Daibatsu Pass, Gokuraku Pass, Kamegayatsu Pass, Kewaizaka Pass, Kobukurozaka Pass, and finally the Nagoshi Pass.

As the topography of Kamakura is like that of a natural fortress—flanked on three sides by mountainous terrain and on one side by the ocean—the Kamakura shogunate saw the need to allow traders access to the city, while at the same time providing for the safeguard of such entrances by making them easy to defend. The answer was the Seven Passes, otherwise known as the Nana Kiri Doshi, which consist of the Asaina Pass, Daibatsu Pass, Gokuraku Pass, Kamegayatsu Pass, Kewaizaka Pass, Kobukurozaka Pass, and finally the Nagoshi Pass.

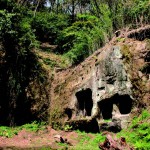

Yagura Tombs

Ancient Tombs Carved in the Hillsides

Initiated during the Muromachi Period around the mid-1400s, these passes are essentially cut strategically from hillsides, enabling transportation to and from neighboring areas. Some of the passes are so narrow a horse can barely squeeze through, and security posts were often perched high atop the hillsides in order to ambush any enemy that attempted to rush through.

Initiated during the Muromachi Period around the mid-1400s, these passes are essentially cut strategically from hillsides, enabling transportation to and from neighboring areas. Some of the passes are so narrow a horse can barely squeeze through, and security posts were often perched high atop the hillsides in order to ambush any enemy that attempted to rush through.

It is near these ancient passes that another of Kamakura’s hidden treasures resides: the Yagura Tombs.

Eisho – ji Temple

Kamakura’s Nunnery

The hills surrounding Kamakura also boast another treasure: cavernous tombs and cenotaphs, known as yagura. Much is still unknown concerning these sites, which are said to be quite numerous—totaling up to 4,000— and possibly date back to 1242, when the Kamakura shogunate forbade the use of flat land for burial purposes, perhaps due to lack of space. Thus, tombs were carved into Kamakura’s abundant steep hillsides in order to bury the ashes of prominent societal figures, such as samurai, priests, and in some cases, artisans. Today, Kamakura’s more well-known yagura can be found along common hiking trails that circle the city’s forested and mountainous areas. These sites include the Karaito Yagura, which is said to have once been an underground prison, and the yagura at the Meigetsu-in Temple, which is the largest yagura in all of Kamakura. When visiting remote yagura, flashlights and proper footwear are recommended.

The hills surrounding Kamakura also boast another treasure: cavernous tombs and cenotaphs, known as yagura. Much is still unknown concerning these sites, which are said to be quite numerous—totaling up to 4,000— and possibly date back to 1242, when the Kamakura shogunate forbade the use of flat land for burial purposes, perhaps due to lack of space. Thus, tombs were carved into Kamakura’s abundant steep hillsides in order to bury the ashes of prominent societal figures, such as samurai, priests, and in some cases, artisans. Today, Kamakura’s more well-known yagura can be found along common hiking trails that circle the city’s forested and mountainous areas. These sites include the Karaito Yagura, which is said to have once been an underground prison, and the yagura at the Meigetsu-in Temple, which is the largest yagura in all of Kamakura. When visiting remote yagura, flashlights and proper footwear are recommended.

Having not always been open to the public, Eishō-ji Temple is a relatively unknown Kamakura temple, effectively standing as Kamakura’s only nunnery. It is also known to some as the ‘temple of flowers’—multitudes of magnificently colored flowers stand proudly in its famous garden, making it one of the most stunning photo opportunities in the area. Built in 1638, the temple had strong relations to the Tokugawa shogunate, and thus maintained a high status compared to other temples in the area at that time. In 1923 the temple was hit by the Great Kanto Earthquake; however the altar, gate, and bell tower survived without a scratch. The temple is also well known for its ceiling mural of the Buddhist Heavenly World, with a dragon at the center, circled by celestial maidens playing the flute.

Having not always been open to the public, Eishō-ji Temple is a relatively unknown Kamakura temple, effectively standing as Kamakura’s only nunnery. It is also known to some as the ‘temple of flowers’—multitudes of magnificently colored flowers stand proudly in its famous garden, making it one of the most stunning photo opportunities in the area. Built in 1638, the temple had strong relations to the Tokugawa shogunate, and thus maintained a high status compared to other temples in the area at that time. In 1923 the temple was hit by the Great Kanto Earthquake; however the altar, gate, and bell tower survived without a scratch. The temple is also well known for its ceiling mural of the Buddhist Heavenly World, with a dragon at the center, circled by celestial maidens playing the flute.

Built in 1638, the temple had strong relations to the Tokugawa shogunate, and thus maintained a high status compared to other temples in the area at that time. In 1923 the temple was hit by the Great Kanto Earthquake; however the altar, gate, and bell tower survived without a scratch. The temple is also well known for its ceiling mural of the Buddhist Heavenly World, with a dragon at the center, circled by celestial maidens playing the flute.

Ofuna Kannon Temple

The Temple of Peace, Love and Understanding

For those riding the JR Takaido Line through Ōfuna for the first time, the surprisingly huge statue of the Kannon resting on the top of a large hill at the Ōfuna Kannon Temple may have been cause for a second glance.

For those riding the JR Takaido Line through Ōfuna for the first time, the surprisingly huge statue of the Kannon resting on the top of a large hill at the Ōfuna Kannon Temple may have been cause for a second glance.

The temple’s 25-meter high, ivory colored statue of the Kannon is as daunting as it is large, but don’t be intimidated. This Buddhist temple, which is dedicated to the Bodhisattva, and the statue, which represents the Goddess of Mercy of the White Robe, welcomes any and all foreigners—as the Kannon’s image is portrayed similarly throughout most of Buddhist Asia. As stated in its official literature, the temple provides a “welcome sense of familiarity to foreigners living in Japan who seek her out as a source of comfort during periods of solitude and homesickness. The goddess of mercy carries the prayers for peace of foreigners and Japanese citizens alike.”

Constructed in 1929 and finally finished in 1960, this temple is a more recent piece of Kamakura history. Another highlight of the temple is its few pieces of very important rock: stones from the burning remains of Nagasaki and Hiroshima are on display to commemorate the victims of World War II’s atomic bomb attacks.

Tosho -ji Temple

Scattered Remains of one of Kamakura’s Finest

Tucked into a hillside of the Kasaigayatsu valley in today’s Ōmachi area, the Tōshō-ji Temple seems to have almost been forgotten. According to the Taiheki, a historical Japanese epic written in the 14th century, every regent from the time of the temple’s construction in 1237 to the end of the Kamakura shogunate was buried here. Despite its historical significance, its function as a tourist attraction is complicated by its location—it sits at the top of a narrow valley blocked by the adjacent gorge of the Namerigawa river. However, what is left of the temple is commemorated with a signpost detailing the death of the entire Hōjō clan—the regents of Kamakura under the Kamakura shogunate—at the hands of Yoshisada Nitta and his troops. They shut themselves inside the temple and lit it aflame, destroying everything. Later, the temple was restored, even to the point that it was listed as third in the top ten temples of the Kanto area, but was abandoned during the Sengoku Era (1467–1573). Additionally, 100 meters above the temple sits the Hara-kiri Yagura, where in 1333, according to legend, the last of the Hōjō clan—870 people in total—collectively disemboweled themselves as they watched their temple and city burn after the fatal attack.

External Link:

Kamakura Travel Guide

Updated On July 17, 2013